2.6 A Theory of Justice

LEARNING OBJECTIVESBy the end of this section, you will be able to:

This chapter began with an image of Justice holding aloft scales as a symbol of equilibrium and fairness. It ends with an American political philosopher for whom the equal distribution of resources was a primary concern. John Rawls (1921–2002) wanted to change the debate that had prevailed throughout the 1960s and 1970s in the West about how to maximize wealth for everyone. He sought not to maximize wealth, which was a utilitarian goal, but to establish justice as the criterion by which goods and services were distributed among the populace. Justice, for Rawls, had to do with fairness—in fact, he frequently used the expression justice as fairness—and his concept of fairness was a political one that relied on the state to take care of the most disadvantaged. In his justice theory, offered as an alternative to the dominant utilitarianism of the times, the idea of fairness applied beyond the individual to include the community as well as analysis of social injustice with remedies to correct it. |

Justice Theory

Rawls developed a theory of justice based on the Enlightenment ideas of thinkers like John Locke (1632–1704) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), who advocated . Social contract theory held that the natural state of human beings was freedom, but that human beings will rationally submit to some restrictions on their freedom to secure their mutual safety and benefit, not subjugation to a monarch, no matter how benign or well intentioned. This idea parallels that of Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), who interpreted human nature to be selfish and brutish to the degree that, absent the strong hand of a ruler, chaos would result. So people willingly consent to transfer their autonomy to the control of a sovereign so their very lives and property will be secured. Rousseau rejected that view, as did Rawls, who expanded social contract theory to include justice as fairness. In A Theory of Justice (1971), Rawls introduced a universal system of fairness and a set of procedures for achieving it. He advocated a practical, empirically verifiable system of governance that would be political, social, and economic in its effects.

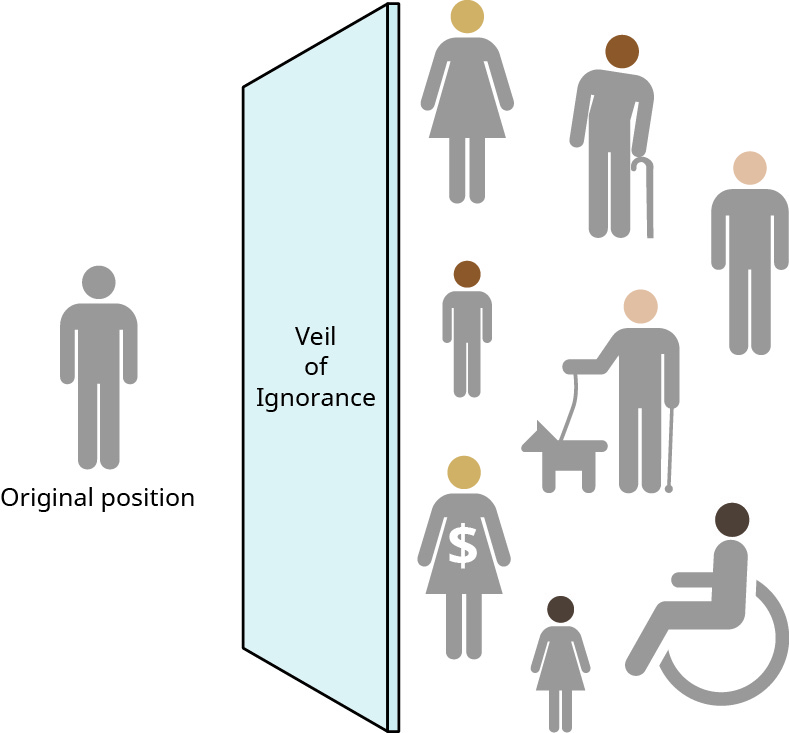

Rawls’s justice theory contains three principles and five procedural steps for achieving fairness. The principles are (1) an “original position,” (2) a “veil of ignorance,” and (3) unanimity of acceptance of the original position.61 By original position, Rawls meant something akin to Hobbes’ understanding of the state of nature, a hypothetical situation in which rational people can arrive at a contractual agreement about how resources are to be distributed in accordance with the principles of justice as fairness. This agreement was intended to reflect not present reality but a desired state of affairs among people in the community. The veil of ignorance (Figure 2.10) is a condition in which people arrive at the original position imagining they have no identity regarding age, sex, ethnicity, education, income, physical attractiveness, or other characteristics. In this way, they reduce their bias and self-interest. Last, unanimity of acceptance is the requirement that all agree to the contract before it goes into effect. Rawls hoped this justice theory would provide a minimum guarantee of rights and liberties for everyone, because no one would know, until the veil was lifted, whether they were male, female, rich, poor, tall, short, intelligent, a minority, Roman Catholic, disabled, a veteran, and so on.

The five procedural steps, or “conjectures,” are (1) entering into the contract, (2) agreeing unanimously to the contract, (3) including basic conditions in the contract such as freedom of speech, (4) maximizing the welfare of the most disadvantaged persons, and (5) ensuring the stability of the contract.62 These steps create a system of justice that Rawls believed gave fairness its proper place above utility and the bottom line. The steps also supported his belief in people’s instinctual drive for fairness and equitable treatment. Perhaps this is best seen in an educational setting, for example, the university. By matriculating, students enter into a contract that includes basic freedoms such as assembly and speech. Students at a disadvantage (e.g., those burdened with loans, jobs, or other financial constraints) are accommodated as well as possible. The contract between the university and students has proven to be stable over time, from generation to generation. This same procedure applies on a micro level to the experience in the classroom between an individual teacher and students. Over the past several decades—for better or worse—the course syllabus has assumed the role of a written contract expressing this relationship.

Rawls gave an example of what he called “pure procedural justice” in which a cake is shared among several people.63 By what agreement shall the cake be divided? Rawls determined that the best way to divide the cake is to have the person slicing the cake take the last piece. This will ensure that everyone gets an equal amount. What is important is an independent standard to determine what is just and a procedure for implementing it.64

The Problem of Redistribution

Part of Rawls’s critique of utilitarianism is that its utility calculus can lead to tyranny. If we define pleasure as that which is popular, the minority can suffer in terrible ways and the majority become mere numbers. This became clear in Mills’s attempt to humanize Bentham’s calculus. But Mills’s harm principle had just as bad an effect, for the opposite reason. It did not require anyone to give up anything if it had to be done through coercion or force. To extend Rawls’s cake example, if one person owned a bakery and another were starving, like Jean Valjean’s sister in Les Misérables, utilitarianism would force the baker to give up what he had to satisfy the starving person without taking into account whether the baker had greater debts, a sick spouse requiring medical treatment, or a child with educational loans; in other words, the context of the situation matters, as opposed to just the consequences. However, Mill’s utilitarianism, adhering to the harm principle, would leave the starving person to his or her own devices. At least he or she would have one slice of cake. This was the problem of distribution and redistribution that Rawls hoped to solve, not by calculating pleasure and pain, profit and loss, but by applying fairness as a normative value that would benefit individuals and society.65

The problem with this approach is that justice theory is a radical, egalitarian form of liberalism in which redistribution of material goods and services occurs without regard for historical context or the presumption many share that it inherently is wrong to take the property legally acquired by one and distribute it to another. Rawls has been criticized for promoting the same kind of coercion that can exist in utilitarianism but on the basis of justice rather than pleasure. Justice on a societal level would guarantee housing, education, medical treatment, food, and the basic necessities of life for everyone. Yet, as recent political campaigns have shown, the question of who will pay for these guaranteed goods and services through taxes is a contentious one. These are not merely fiscal and political issues; they are philosophical ones requiring us to answer questions of logic and, especially in the case of justice theory, fairness. And, naturally, we must ask, what is fair?

Rawls’s principles and steps assume that the way in which the redistribution of goods and services occurs would be agreed upon by people in the community to avoid any fairness issues. But questions remain. For one, Rawls’s justice, like the iconic depiction, is blind and cannot see the circumstances in which goods and services are distributed. Second, we may question whether a notion of fairness is really innate. Third, despite the claim that justice theory is not consequentialist (meaning outcomes are not the only thing that matters), there is a coercive aspect to Rawls’s justice once the contract is in force, replacing utility with mandated fairness. Fourth, is this the kind of system in which people thrive and prosper, or, by focusing on the worst off, are initiative, innovation, and creativity dampened on the part of everyone else? Perhaps the most compelling critic of Rawls in this regard was his colleague at Harvard University, Robert Nozick (1938–2002), who wrote A Theory of Entitlement (1974) as a direct rebuttal of Rawlsian justice theory.66 Nozick argued that the power of the state may never ethically be used to deprive someone of property he or she has legally obtained or inherited in order to distribute it to others who are in need of it.

Still, one of the advantages of justice theory over the other ethical systems presented in this chapter is its emphasis on method as opposed to content. The system runs on a methodology or process for arriving at truth through the underlying value of fairness. Again, in this sense it is similar to utilitarianism, but, by requiring unanimity, it avoids the extremes of Bentham’s and Mill’s versions. As a method in ethics, it can be applied in a variety of ways and in multiple disciplines, because it can be adapted to just about any value-laden content. Of course, this raises the question of content versus method in ethics, especially because ethics has been defined as a set of cultural norms based on agreed-upon values. Method may be most effective in determining what those underlying values are, rather than how they are implemented.

| Figure 2.10 The “veil of ignorance” in Rawls’s “original position.” Those in the original position have no idea who they will be once the veil (wall) has been lifted. Rawls thought such ignorance would motivate people in the community to choose fairly. (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license) |

LINK TO LEARNINGThe “veil of ignorance” is a central concept in Rawls’s justice theory. What is it? What does it attempt to accomplish? Watch this video on how “ignorance can improve decision-making” to explore further. |

||

|

|

||

Justice in Business

Although no ethical framework is perfect or fits a particular era completely, Rawls’s justice theory has distinct advantages when applied to business in the twenty-first century. First, as businesses become interdependent and globalized, they must pay more attention to quality control, human resources, and leadership in diverse settings. What will give greater legitimacy to an organization in these areas than fairness? Fairness is a value that is cross-cultural, embraced by different social groups, and understood by nearly everyone. However, what is considered fair depends on a variety of factors, including underlying values and individual characteristics like personality. For instance, not everyone agrees on whether or how diversity ought to be achieved. Neither is there consensus about affirmative action or the redistribution of resources or income. What is fair to some may be supremely unfair to others. This presents an opportunity for engaged debate and participation among the members of Rawls’s community.

Second, as we saw earlier, justice theory provides a method for attaining fairness, which could make it a practical and valuable part of training at all levels of a company. The fact that its content—justice and fairness—is more accessible to contemporary people than Confucian virtue ethics and more flexible than Kant’s categorical imperative makes it an effective way of dealing with stakeholders and organizational culture.

Justice theory may also provide a seamless way of engaging in corporate social responsibility outwardly and employee development inwardly. Fairness as a corporate doctrine can be applied to all stakeholders and define a culture of trust and openness, with all the corresponding benefits, in marketing, advertising, board development, client relations, and so on. It is also an effective way of integrating business ethics into the organization so ethics is no longer seen as the responsibility solely of the compliance department or legal team. Site leaders and middle managers understand fairness; employees probably even more so, because they are more directly affected by the lack of it. Fairness, then, is as much part of the job as it is an ongoing process of an ethics system. It no doubt makes for a happier and more productive workforce. An organization dedicated to it can also play a greater role in civic life and the political process, which, in turn, helps everyone.

WHAT WOULD YOU DO?John Rawls’s Thought ExperimentJohn Rawls’s original position represents a community in which you have no idea what kind of person you will end up being. In this sense, it is like life itself. After all, you have no idea what your future will be like. You could end up rich, poor, married, single, living in Manhattan or Peru. You might be a surgeon or fishing for sturgeon. Yet, there is one community you will most likely be a part of at some point: the aged. Given that you know this but are not sure of the details, which conditions would you agree to now so that senior citizens are provided for? Remember that you most likely will join them and experience the effects of what you decide now. You are living behind not a spatial veil of ignorance but a temporal one.

Critical Thinking

|

Citation/Attribution

Attribution information

- If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a print format, then you must include on every physical page the following attribution:

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a digital format, then you must include on every digital page view the following attribution:

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

Citation information

- Use the information below to generate a citation. We recommend using a citation tool such as this one.

- Authors: Stephen M. Byars, Kurt Stanberry

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Business Ethics

- Publication date: Sep 24, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

© Dec 12, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.