3.3 Ethical Decision-Making and Prioritizing Stakeholders

LEARNING OBJECTIVESBy the end of this section, you will be able to:

If we carry the idea of stakeholder to the extreme, every person is a stakeholder of every company. The first step in stakeholder management, the process of accurately assessing stakeholder claims so an organization can manage them effectively, is therefore to define and prioritize stakeholders significant to the firm. Then, it must consider their claims. Given that there are numerous types of stakeholders, how do managers balance these claims? Ethically, no group should be treated better than another, and managers should respond to as many stakeholders as possible. However, time and resource limitations require organizations to prioritize claims as stakeholder needs rise and fall.

|

Stakeholder Prioritization

First, it may help to speak to the expectations that any stakeholders may have of a particular business or institution. It depends on particular stakeholders, of course, but we can safely say that all stakeholders expect a form of satisfaction from an organization. If these stakeholders are shareholders (stockowners), then they generally wish to see a high return on their purchase of company shares. If, on the other hand, they are employees, they typically hope for interesting tasks, a safe work environment, job security, and rewarding pay and benefits. If, yet again, the stakeholders are members of the community surrounding a business, they usually wish that the company not harm the physical environment or degrade the quality of life within it.

So the task confronting an organization’s management begins with understanding these multiple and sometimes conflicting expectations and ethically deciding which stakeholders to focus on and in what sequence, if not all stakeholders cannot be addressed simultaneously, that is, stakeholder prioritization. It helps to actively gather information about all key stakeholders and their claims. First, managers must establish that an individual with a concern is a member of a stakeholder group. For example, a brand may attract hundreds or thousands of mentions on Twitter each day. Which ones should be taken seriously as representative of key stakeholders? Brand managers look for patterns of communication and for context when deciding whether to engage with customers in the open expanses of social media platforms.

LINK TO LEARNINGRead this article “Five Questions to Identify Key Stakeholders” in the Harvard Business Review to learn more about identifying your key stakeholders.

|

After establishing that a key stakeholder group is being represented, the manager should identify what the company needs from the stakeholder. This simply helps clarify the relationship. If nothing is needed immediately or for the foreseeable future, this does not mean the stakeholder group does not matter, but it can be a good indication that the stakeholder need not be prioritized at the moment.

Note that managers are often considering these questions in real time, usually with limited resources and power, and that circumstances can change in a matter of moments. In one sense, all representatives of a company are constantly practicing stakeholder prioritization. It need not be a formal process. At times, it is a question of which supplier should be praised or prodded or which customer has a larger order to fill or a special request that might be met. What matters is establishing that someone is a stakeholder, that the concern is currently important, and that the relationship matters for the growth of the business.

If the firm cannot survive without this particular stakeholder or replace him or her relatively easily, then such a person should have priority over other stakeholders who do not meet this criterion. Key suppliers, lucrative or steady customers, and influential regulators must all be attended to but not necessarily capitulated to. For example, a local state legislator representing the district where a business is located may be urging the legislature to raise business taxes to generate more revenue for the state. By him- or herself, the legislator may not have sufficient political clout to persuade the legislature to raise taxes. Yet wise business leaders will not ignore such a representative and will engage in dialogue with him or her. The legislator may eventually be able to win others over to the cause, so it behooves perceptive management to establish a working relationship with him or her.

Not every stakeholder can command constant attention, and no firm has unlimited time or resources, so in one sense, this prioritizing is simply the business of management. Combine the inherent priority of the stakeholder relationship with the level of exigency, that is, the level of urgency of a stakeholder claim, to arrive at a decision about where to begin focusing resources and efforts.

Stakeholder prioritization will also vary based on time and circumstance. For example, a large retailer facing aggressive new competitors must prioritize customer service and value. With Amazon acquiring Whole Foods and drastically cutting prices, the grocery chain’s customer base may very well grow because prices could become more attractive while the perception of high quality may persist. Potential customers may no longer need to economize by shopping elsewhere.17 Whole Foods’ competitors, on the other hand, must now prioritize customer service, whereas before they could compete on price alone. Whole Foods can become a serious competitor to discount grocery stores like ALDI and Walmart.

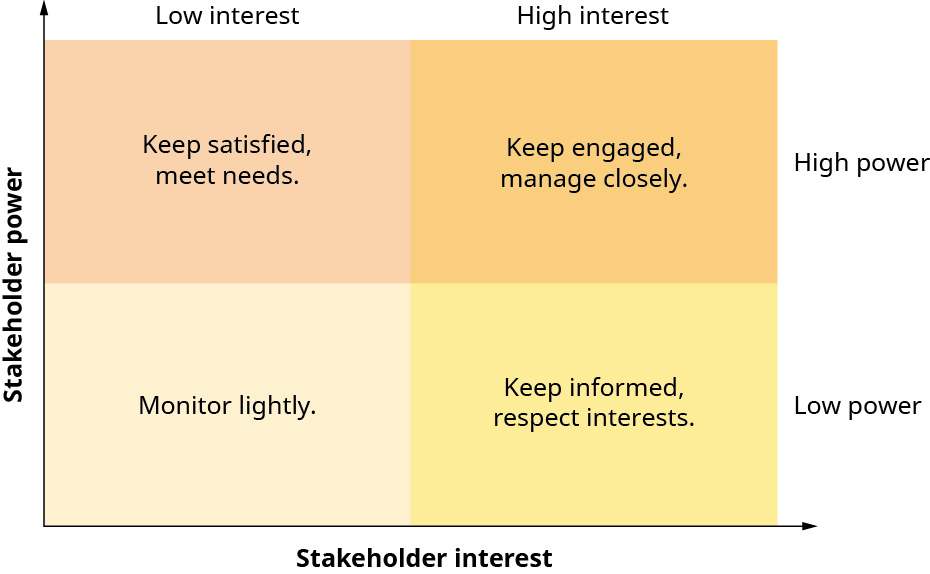

Another way to prioritize stakeholder relationships is with a matrix of their power and interest. As Figure 3.5 shows, a stakeholder group can be weighted on the basis of its influence (or power) over and interest in its relationship to the firm. A stakeholder with a high level of both power and interest is a key stakeholder. If this type of stakeholder group encounters a problem, its priority rises.

| Figure 3.5 Stakeholder priority can be expressed as a relationship between the stakeholder group’s influence or power and the interest the stakeholder takes in the relationship. (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license) |

On the supplier side, a small farmer or seasonal supplier could fall in the low-power, low-interest category, particularly if that farmer were selling various retailers produce from his or her fields. However, if that same farmer could connect to a huge purveyor like Kroger, he or she could sell this giant customer its entire crop. This relationship places the farmer in the low-power, high-interest category, meaning he or she will most likely have to make price adjustments to make the sale.

The model’s focus on power reveals a need for any company to carefully cultivate relationships with stakeholders. Not all stakeholders have equal influence with a firm. Still, no organization can blithely ignore any stakeholder without potentially debilitating economic consequences. For example, now that Amazon has acquired Whole Foods and increased the size of the customer stakeholder group, it must also find ways to personalize its communications with this group, because personal service has traditionally been more a hallmark of Whole Foods than of Amazon.

Successful business practice today hinges on the ethical acknowledgement of stakeholder claims. It is the right thing to do. Not only that, it also engenders satisfied stakeholders, whether they be customers, stockowners, employees, or the community in which a firm is located. Naturally, satisfied stakeholders lead to the financial well-being of a company.

Managing Stakeholder Expectations

Stakeholder management does not work if the firm’s prioritizing decisions are based on flawed, inaccurate, or incomplete information. Some tools are available to help. MITRE is a nonprofit research and development consulting firm that helps governments and other large organizations with many stakeholders conduct stakeholder assessment. The MITRE Guide to Stakeholder Assessment and Management lays out a five-step system for stakeholder management.18

Overall, MITRE stresses that an organization must sustain trust with its stakeholders through communication efforts. To accomplish this, however, stakeholders must first be clearly identified and then periodically reidentified, because stakeholder cohorts change in size and significance over time. The concerns or claims of stakeholders are identified through data gathering and analysis. Sometimes a firm will conduct surveys or focus groups with customers, suppliers, or other stakeholders. Other times, product usage data will be available as a function of sales figures and marketing data. For software in web and mobile applications, for example, user data may be readily available to show how stakeholders are using the company’s digital services or why they appear to be purchasing its products. Another source of stakeholder data is social media, where firms can monitor topics stakeholders of all types are talking about. What matters is gathering relevant and accurate data and ensuring that key stakeholders are providing it. In the next step, managers present the results of their research to the company’s decision makers or make decisions themselves.19 Finally, stakeholders should be informed that their concerns were taken into consideration and that the company will continue to heed them. In other words, the firm should convey to them that they are important.

LINK TO LEARNINGOne methodology for prioritizing stakeholder claims is the Stakeholder Circle, developed by Dr. Linda Bourne. Visit the Stakeholder Management website detailing the five key actions an organization can take using this model to learn more.

|

WHAT WOULD YOU DO?Malaysia AirlinesMalaysia Airlines is owned by individual investors and the Malaysian government, which took over the company in 2014 after two mysterious jet crashes. The airline has lost money and struggled since that time, going through three CEOs. The current CEO, Peter Bellew, is experienced in tourism and travel and has been asked to cut costs and increase revenues. His strategy is to maximize the number of Malaysian Muslims (who make up more than 60 percent of the population) flying to Mecca for hajj, the annual holy pilgrimage and an obligation for all Muslims who are well enough to travel and can afford the trip. Bellew plans to provide charter flights to make the pilgrimage easier on travelers.20 Critical Thinking

|

Because every firm, no matter its mission, ultimately depends on the marketplace, its clients or customers are often high-priority stakeholders. Ethically, the company owes allegiance to customer stakeholders, but it also has an opportunity and perhaps a responsibility to shape their expectations in ways that encourage its growth and allow it to continue to provide for employees, suppliers, distributors, and shareholders.

We should note, too, that nonprofit organizations are beholden, for the most part, to the same rules that apply to for-profits for their sustainability. Nonprofits typically provide a service that is just as dependent on cash flow as is the service or product of a for-profit. A significant difference, of course, is that the client or customer for a nonprofit’s service often is unable to pay for it. Therefore, the necessary cash must come from other sources, often in the form of donations or endowments. Hence, those who give to philanthropies constitute essential stakeholders for these nonprofits and must be acknowledged as such.

Wesley E. Lindahl, who studies and advises nonprofits, notes that philanthropies have an ethical obligation to safeguard the donations that come their way. He likens this to a stewardship, because the monies given to charities are gifts intended for others very much in need of them. So those who manage nonprofits have a special obligation to ensure that these donations are well spent and distributed appropriately.21

There are three major components to bringing about change in customer or donor expectations: (1) customer receptivity to a product or service offered by the company, (2) acknowledgement of the gap between customer receptivity and corporate action to reduce it, and (3) a system to bring about and maintain change in customer desires to bring it in line with precisely what the corporation can deliver. One example of firms altering customers’ habits is the evolution of beverage containers. Most soft drinks and other beverages such as beer were once delivered in reusable glass bottles. Customers were motivated to return the bottles by the refund of a minimal cash deposit originally paid at the time of purchase. The bottles had to be thick and sturdy for reuse, which resulted in substantial transportation costs, due to their weight.

To reduce these costs of manufacturing and transportation, manufacturers first redesigned production to be local, and then, when technology allowed, introduced aluminum cans and pull tabs. Eventually, the cardboard carton that held bottles together was replaced by a plastic set of rings to hold aluminum cans together. Now, however, customers and other stakeholders object to the hazard these rings present to wildlife. Some firms have responded by redesigning their packaging yet again. This ongoing process of developing new packaging, listening to feedback, and redesigning the product over time ultimately changed stakeholder behavior and modernized the beverage industry. Stakeholders are essential parts of a cycle of mutual interest and involvement.

ETHICS ACROSS TIME AND CULTURESGoing King Sized in the United States and Crashing on the Couch in ChinaIKEA is a multinational corporation with a proven track record of listening to stakeholders in ways that improve relationships and the bottom line. The Swedish company has had success in the United States and, more recently, in China by adapting to local cultural norms. For example, in the United States, IKEA solicited the concerns of many of its approximately fifty thousand in-store customers and even visited some at home. The company learned, among other things, that U.S. customers assumed IKEA featured only European-size beds. In fact, IKEA has offered king-size beds for years; they simply were not on display. IKEA then began to focus on displaying furniture U.S. consumers were more familiar with and so grew its bedroom furniture sales in 2012 and 2013.22 As IKEA expands into China, it has welcomed a different trend—people taking naps on the furniture on display. “While snoozing is prohibited at IKEA stores elsewhere, the Swedish retailer has long permitted Chinese customers to doze off, rather than alienate shoppers accustomed to sleeping in public.”23 Adapting to local culture, as these examples demonstrate, is one way a company can respond to stakeholder wishes. The firm abandons some of its usual protocols in exchange for increasing consumer identification with its products. IKEA appears to have learned what many companies with a global presence have concluded: Stakeholders, and particularly consumer-stakeholders, have different expectations in different geographic settings. Because a firm’s ethical obligations include listening and responding to the needs of stakeholders, it behooves all international companies to appreciate the varying perspectives that geography and culture may produce among them. Critical Thinking

|

The ethical responsibility of a stakeholder is to make known his or her preferences to the companies he or she purchases from or relies on. Such communication can lead to an increased commitment on the part of corporations to improve. To the extent they do so, companies act more ethically in responding to the wishes and needs of their stakeholders.

Citation/Attribution

Attribution information

- If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a print format, then you must include on every physical page the following attribution:

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a digital format, then you must include on every digital page view the following attribution:

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

Citation information

- Use the information below to generate a citation. We recommend using a citation tool such as this one.

- Authors: Stephen M. Byars, Kurt Stanberry

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Business Ethics

- Publication date: Sep 24, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

© Dec 12, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.