AgriSolar Shelters: Facilitating Regeneration of Soil, People & Communities

AgriSolar Shelters: Facilitating Regeneration of Soil, People & Communities

Irene Herremans

Tatenda Mambo, a post-doc scholar at the University of Calgary, was in the middle of a workshop on regenerative agriculture when the sky turned from a bright sunny day to a sky filled with dark grey, low-hanging clouds. As usual, the weather had changed without much advance warning in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Only 45 minutes from the mountains, the weather is a continuous surprise. It is often stated as the best thing and the worst thing about Calgary, depending on one’s point of view.

However, given that the climate has been changing over the past few years, it is not only the Calgary region that has difficulties adjusting to the weather. Many parts of the world are experiencing unusual weather conditions. Snow appears more often in locations that rarely get snow and other than during normal seasons. Flooding comes more frequently, and dry regions are getting even drier or sometimes flood. These changing and unexpected weather conditions create problems for gardeners.

Tatenda acted quickly. “Come on, everyone! Let’s run for shelter. Not sure what the weather will do, just rain or hail. It doesn’t look pleasant.”

Soon, everyone was heading for the shelter in the centre of the community garden. Within a few minutes, the ground became peppered with white balls of hail. Although they were not golf ball-sized, they were large enough to do damage to the fragile garden plants in the community garden, referred to as Land of Dreams. Land of Dreams was created by the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society in partnership with Indigenous leaders to offer refugees and immigrants a piece of home in a foreign land, where they can work with the soil as they did in their home countries. The space also creates opportunities for new immigrants to connect with the Indigenous community, learning about the history of the land and the people who stewarded it for centuries. It offered the new residents of Calgary, coming from all different parts of the world, an opportunity to grow the crops they are used to eating, bringing some familiarity to their new surroundings.

“What will happen to our plants?” asked Katalin. “Will all our hard work be destroyed?”

Tatenda did not know how to answer. He tried to instil hope by assuring them that their plants would live through the hail, but it depended on how long the hail lasted and how large the little snowballs grew. Tatenda responded: “Hopefully, the hail will not last long, and the storm will pass over soon. If this happens, your plants should not suffer much damage.” However, at the same time, he knew the new residents were anxious about losing the plants that they had so meticulously cared for over the last several weeks. Tatenda thought about the situation as he was waiting for the storm to stop. He was happy to see the hail stop a few minutes later.

Everyone ran out to assess the damage. Ivan and Natasha, a husband-and-wife team, were the first to report to the others. “Luckily, the plants survived this time. All our work was not destroyed.”

However, Tatenda knew that these storms could occur frequently, even in the summer months. He hated to see the mixed emotions of the gardeners. They were so excited about using the fruits of their labour in their cooking during the summer, but he was also fearful that all their hard work would not pay off. He knew he needed a better solution than hoping the hail would not last long and would not damage the plants. He decided he would talk to a couple of his colleagues to see if there was a solution.

When Tatenda arrived home that evening, he sat down at his computer and wrote an email to Steve O’Gorman and Irene Herremans. Steve was a technical designer of infrastructure equipment for many years. He was now CEO of his own company called Star Energy Solutions. Irene was a professor at the University of Calgary who taught in a trans-disciplinary program in Sustainable Energy Development. It was a Master of Science graduate program in which the students took engineering, business, law, and environmental design courses. The coursework was integrated into a capstone research project, often with an interested organisation. Steve and Irene had worked with Tatenda on a variety of projects in the past, with frequent success.

Tatenda explained the situation regarding the hail at the Land of Dreams community garden and asked if they had any potential solutions. Irene returned the email first.

She wrote: “I just attended a meeting on agrivoltaics that are being installed in the United States for slightly different purposes. Agrivoltaics allow farming equipment to run under the infrastructure, so the land is still useful for agricultural purposes. In locations with very hot climates and not much rain, it also shades the crops to use less water for irrigation. I wonder if we could adapt some of these ideas to protect the plants from the hail and even the cold nights that we sometimes get in Calgary and other locations in Canada. Some sort of shelter to protect the plants could also extend the season for the gardeners. And with climate conditions changing, I think other regions of the country could use some crop protection. It might even work in the northern regions for the Indigenous communities to grow some of their own food rather than having it flown in at huge cost and burning all that fossil fuel in transport?”

Steve then answered: “This is an interesting idea. Do you think we could adapt some of the characteristics of the agrivoltaics to a type of greenhouse or shelter that could have solar panels to heat it, if necessary, and to provide energy for hydroponics or other energy needs in the greenhouse?”

Tatenda answered back: “If we could sell any excess energy to the grid, it would then supply some revenue to the gardeners for any supplies and equipment that they might need. Also, if we could figure out a way to capture rainwater, they could decrease the cost of using water for irrigation.”

Steve ended the conversation with this message: “Leave this with me and I will bring back a design that we can review in a couple of weeks.”

Steve worked diligently on the design, seeking advice from some of his acquaintances who were more familiar with greenhouses than he was. He finally had a design to show Tatenda and Irene. Steve let them know he was ready for the unveiling. He suggested that they get together at Sam’s Diner for lunch to explain the details to them, and they could provide him with feedback.

Here is how he described the concept. “The design of the Agri-solar Shelter is sustainable regarding the use of local goods and services. It would also have end-of-life recycling. As well, the design is transferable and adaptable to diverse local requirements depending on the location, and shelter assembly is repeatable with a high degree of quality assurance.”

He quickly reviewed a list of bullet points that he felt were essential for financial, environmental, and social sustainability.

- Increase food production at community gardens. \

- Shelter crops from harsh weather (winter low temperature, summer high temperature, wind, hail, frost, and snow).

- Protect crops from foraging animals and pests.

- Ensure pollinator access and support pollinator habitat.

- Reduce crop temperatures and corresponding water evaporation rates during the summer growing season.

- Winterise to protect crops and equipment from cold temperatures and winds during the winter growing season.

- Support a high degree of energy and water self-reliance.

- Connect to the local electrical utility to enhance reliability.

- Ensure affordable access through very low operating costs.

- Ensure a low carbon footprint in the construction and operation of shelters.

- Provide a robust design with material selection based upon a 20-year life cycle.

- Facilitate phased construction through modular design of the structure, energy systems and rainwater harvesting tanks.

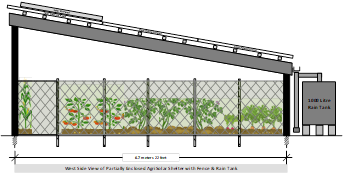

He continued: “The food gardens and plant nurseries in the sheltered space are complementary to the energy provided by the solar PV panels and the rainwater harvesting provided by the polycarbonate panels that form the roof. The sheltered space will have adequate natural light for plant growth, plus supplemental LED grow lights for early spring and late fall operations. It will feature lower temperatures and evaporation rates during peak high temperatures. For operations during colder temperatures, thermal energy storage can be provided by a cinder block wall on the north side of the shelter.”

Steve then provided more details about the design along with cost estimates for the Agri-solar Shelter (see Appendix A):

- Other than supplemental lighting and freeze protection for the water tanks, equipment for other potential loads is not included in the scope of supply.

- The productive use of energy will be determined by the community based on needs and priorities.

- Even though not included in the design or cost estimate, battery energy storage is available as an option.

· Rainwater is suitable for crop irrigation, with additional water processing equipment required for human consumption, food cleaning , or processing for market sale.

· Soil, seeds, irrigation piping and other gardening inputs are not included in the cost estimate.

· The conceptual design of the shelter is based upon local conditions and the use of standard lumber available in Canada. It is assumed the conceptual design will be engineered by a local engineer based on local conditions and the availability of suitable wood products. The final design could affect the budget required to build the structure.

· Details associated with the connection of the solar PV system to the local power grid need to be fully understood. A cost analysis has not been undertaken, and the cost to the project has not been included in the cost estimate.

After Steve explained the design of what he called the Agri-solar Shelter to differentiate it from conventional greenhouses, he received praise from Tatenda and Irene for his innovation. However, they both had a few suggestions for improvement.

Tatenda was first to provide his feedback: “One of the problems with greenhouses is that pollinators cannot get in. Maybe we could devise a method of opening the sides or rolling up the sides when the plants do not need protection, so pollinators could do their work. Do you think that might be possible, Steve?”

“Let me give that some thought,” Steve replied. “If feasible, that would be an excellent idea to make it more attractive than conventional greenhouses.”

Irene had some thoughts as well. “You know, we are trying to make this a more sustainable alternative to conventional greenhouses by using renewable energy for heat, if necessary, and other energy needs. However, perhaps we should analyse to determine if its benefits exceed those of the conventional greenhouses. For example, we would be saving on greenhouse gas emissions by using solar rather than natural gas. What other environmental benefits would exist, and can we monetise or at least quantify the potential outcome?”

Irene continued: “Tatenda, you are teaching the gardeners how to regenerate the land naturally, so artificial fertilisers and chemicals are not needed. Of course, the shelter would help the gardeners save money on their grocery bills, but does it stand the test of all three dimensions of sustainability: financially, environmentally, and socially? What would the social benefits be? They are always more difficult to identify and quantify….but there must be some.”

Steve was the first to answer: “Well, of course, there are social benefits. Have you read any of the research on the feeling of accomplishment when gardeners can put their own home-grown food on the table for their family and guests? There are enormous benefits. Furthermore, the research also shows that gardeners who get their hands in the dirt develop better mental health. It is not quite the same as what the Japanese refer to as forest bathing, but those are just a few of many.”

Tatenda agreed, but he had some concerns: “But how do you measure those social benefits. How do we capture self-determination and their ability to advocate for their own food needs? They are not as easy as measuring the financial or environmental benefits.”

There was silence. Everyone was thinking about how to quantify all the benefits and what the next steps would be.

Then Irene spoke up. “We need an analysis of the benefits and concerns in all three sustainability dimensions: financial, environmental, and social. In this way, we could make a better decision about the fit for the gardeners. However, we must also communicate with the gardeners at Land of Dreams to see if they are receptive to the idea. They might have some great ideas as to how to proceed. And then we also need a list of construction costs. Let me speak to Anthony, who was one of my MBA students specialising in sustainability and finance. Maybe he can help us put together a list of costs to construct a prototype. Then we could test it out at Land of Dreams to learn more about how to make it a success.”

Irene continued: “Steve let me put you in touch with Anthony, and the two of you can work on getting some costs down on paper.” Let’s meet again in two weeks after we have more details.”

Irene introduced Anthony to Steve, and the two worked together on the list of costs. The team of four met again at the same place for lunch.

Steve and Anthony explained the numbers on the spreadsheet they prepared.

Steve began: “Well, I estimated the total cost to be about $100,000, but that is dependent on size. Some of these costs would change if it were upscaled or downscaled. Solar panels generally last for about 25 years. However, technology is improving all the time. The panels might even last for 30 years. All the other materials are pretty sturdy and have approximately the same life as the panels. There might be an inverter replacement required mid-way through the panel life cycle that would require approximately a $5,000 investment. Otherwise, it is a pretty low-maintenance facility. And if we could get some volunteers to help with the construction, the cost could be reduced.”

Steve continued: Here is a spreadsheet (see Appendix B and spreadsheet). Both of you can review the list of materials and labour and determine if you can find any cost savings. Of course, there would also be revenue generated from the solar panels when the facility is connected to the grid. And maybe the gardeners would want to sell some of their produce to cover maintenance costs or bring in some additional revenue to cover other costs of their gardening work….lots of possibilities.

Anthony commented, “It should be fairly easy to do a straightforward financial analysis: breakeven, payback, or a net present value calculation. The project does not require a high return, as it is not competing with other projects in a corporate setting. Donations and grants might even help fund the initial capital costs, but it should be able to maintain itself financially to keep it in good condition. Furthermore, there should be savings from the environmental aspects of the case that can be included in the analysis. Steve mentioned the concern about measuring the social benefits. I am unsure if those could be worked into the financial analysis, but maybe some proxies could be used. Looking at some of the current standards, such as the Global Reporting Initiative and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, might be helpful.”

Irene replied: “That sounds like a good idea. Let me see if one of the student groups with whom I work is interested in working on the analysis. This is a great experiential learning project and would be very beneficial if they are seeking a career in sustainability in the future. If so, I will have them give us and the Land of Dreams gardeners a presentation of their findings. Then we can make a better decision. Do you agree?”

Tatenda, Steve, and Anthony nodded their heads in agreement and felt it was a logical next step forward. Anthony added: “It might be a good idea to have the student group suggest other opportunities for using the Agri-solar Shelter, such as community gardeners or for the school curriculum. It seems as if there must be many applications for the shelter.”

Everyone agreed that Anthony’s suggestion was worth investigation.

Irene made a few calls and found students who were eager to work on this project and help the local community. She explained that they needed to prepare a presentation for Land of Dreams and the team of Tatenda, Irene, Steve, and Anthony during the next month.

APPENDIX A

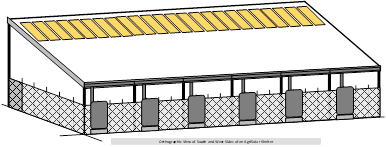

ORTHOGRAPHIC VIEW OF AN AGRISOLAR SHELTER

END VIEW OF AN AGRISOLAR SHELTER

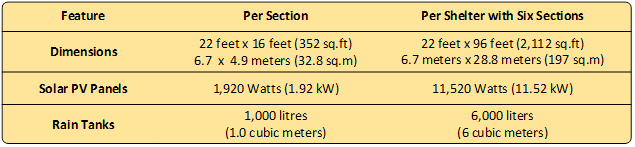

TECHNICAL SUMMARY

APPENDIX B: PRELIMINARY COST ESTIMATE (CAD)

NET ELECTRICAL ANALYSIS

No Comments