Episode 46: Future Core Skills and Knowledge in the ERA of AI

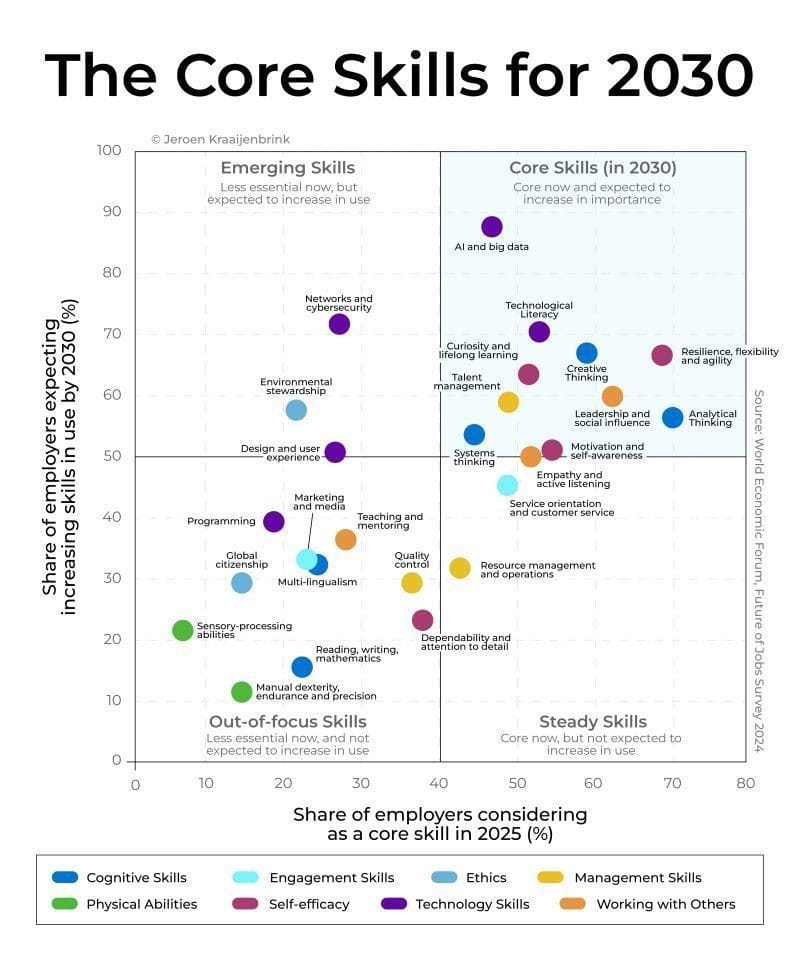

Recently, numerous posts have circulated, citing the WEF’s Core Skills in 2030 found in their “Future of Jobs Survey” in 2024. Below is one of the better images that represents the key results.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Core Skills in 2030

It is interesting to examine how certain skills are positioned on the chart and how a few are grouped together. The first skill I want to highlight is teaching and mentoring, which I believe should be considered distinct and evaluated separately. I’m curious how the rankings might change if assessed independently, especially given that leadership and social influence are in the upper right quadrant. Many of the skills in the upper right quadrant are developed through mentorship, as skills are often cultivated through mentoring rather than traditional teaching. In my opinion, teaching primarily focuses on the acquisition of knowledge. I suspect that the nearly 1,000 students I have interacted with over the past two decades on case-solving teams would say that those interactions mainly involved mentoring, and that the most valued outcomes were related to skill development.

When looking at the skills in the upper right quadrant, I mostly agree with their placements. I also largely agree with the positioning of the other skills. However, one skill that stands out is dependability and attention to detail, which I believe should be shifted into the steady skills quadrant. Additionally, design and user experience should be categorised well within the emerging skills quadrant.

What About Knowledge?

In an article published in Forbes on October 14, 2025, Shannon McKeen raises the question, “When Knowledge Is Free, What Are Professors For?” She begins by noting that many college students rely on AI tools for their school assignments. At the same time, employers frequently express concerns that graduates lack critical thinking and decision-making skills, which are essential for success in an AI-augmented workplace. I believe that these skills have always been vital for career success throughout my time in higher education. Evidence of this is reflected in the career success of my students who have participated in case-solving teams that help them develop these key abilities.

However, I disagree with the assumption that the information provided by AI equates to knowledge, as suggested by the article’s title. The article itself seems to challenge this assumption. While AI can deliver information, it does not necessarily lead to knowledge. Knowledge is gained when students engage in critical thinking and apply various analytical skills to that information. I often observe that many higher education students simply retrieve information, replicate it during exams, and then forget it afterwards. Unfortunately, both AI and many professors tend to focus solely on information delivery while neglecting the importance of skills development. This development is crucial for helping students transform information into knowledge, particularly at the junior level, so they have greater success at senior levels and when they enter the work world..

A Call for Change

As those who have engaged in discussions with me know, I advocate for changes in higher education. Throughout my career, I have prioritised skills development in my interactions with students and have been a strong proponent of experiential education, especially experiences that connect students with their potential future employers.

There are great examples of programs and courses that are doing what is needed to help students develop the “Mad Skills” they need. Some of those are happening at the W. P. Carey School of Business – Arizona State University, Northwestern University - Kellogg School of Management, and Stanford University‘s d.school, as mentioned in the McKeen article. There are other schools doing similar things. This list includes the University of Calgary with its UCalgary Office of Signature Learning Experiences, the huge support for seen case-solving teams at Concordia University - John Molson School of Business, the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University. There are also programs like the Case Track Excellence Centre at Corvinus University of Budapest. As an aside, congratulations to Miklós Stocker, Ph.D., Habil. for the award to the Case Track Excellence Centre as the Teaching Community of the Year at Corvinus. There are also programs like the one I lead with workshops to develop case-solving and skills development at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University in late October, and courses like the Haskayne School of Business‘s ENTI 317 and 201, or the block week case analysis course I have led at Haskayne that focus on skills development and need to become more of the norm.

At many schools, research is prioritised because these institutions are research-focused, and successful research helps secure funding. However, there is a second priority that significantly contributes to funding which are their students. As a faculty member dedicated to teaching, my focus was on how to best prepare students for their future careers. My goal was to produce graduates who would be excellent employees or entrepreneurs, ready to enter the workforce, and this took significant portions of my time outside of my teaching responsibilities, which left little time to focus on research. My former dean was a big supporter and accepted this in my role as a faculty member; in fact, these activities led to my emeritus title upon my retirement.

While leading researchers play a vital role by keeping information current and introducing students to cutting-edge research, not all students receive the opportunities to develop the skills they need. Many schools are addressing this issue by bringing in teaching and learning specialists and implementing structures that provide faculty with the necessary skills to improve their teaching. However, these efforts often fall short when it comes to skills development. Part of this is on students, but I believe that comes from schools failing to develop a culture of skill development with faculty and students alike.

In my discussions with faculty outside of professional schools, I’ve found that there is a strong emphasis on cultivating future researchers, despite the reality that most university graduates will enter the workforce and not pursue formal research careers. Yes, the ability to research is an important skill, but all of those other “Mad Skills” are also important. Higher education needs to deliver “Mad Skills” to all its graduates across all programs. A starting point is to convince students that these skills are necessary and that the university experience is a full experience, not one of sitting in a lecture, taking notes and regurgitating the information on an exam. It’s about making the most of all the opportunities that a student is exposed to in and out of the classroom. My most recent podcast with Rachel Hughes definitely emphasises this, and the advantages of it are seen in Rachel’s early career activities and successes

Who Should be Teaching

There is an ongoing discussion about the evolving requirements in job descriptions for adjunct and teaching-focused positions. Many of these roles list a PhD or another terminal degree as a prerequisite. However, I believe that such a requirement may not be essential for many of these positions. In my observation, terminal degree hires, particularly in business schools, often lack the practical and life experience needed to effectively facilitate skills development. When hiring for teaching-focused positions, candidates who can best deliver the skills required by students must be prioritised..

Recently, I co-taught a course with a Bachelor of Commerce graduate who, based on student feedback, significantly enhanced students’ skill development. She played a vital role in helping our students cultivate the necessary skill set and was regarded as one of the most valuable teachers they encountered during their academic journey.

Additionally, many teaching-focused roles do not require research obligations. While full-time faculty members usually have research responsibilities, teaching-oriented positions may not necessitate the research training associated with a terminal degree, depending on specific job requirements. In my own career, I have successfully collaborated with trained researchers to meet my research needs and have implemented strategies such as case writing. This allowed me to dedicate more time to providing exceptional skill development opportunities for my students. This approach was supported by the dean at the time, who was focused on fostering a positive educational culture.

What Change is Needed

Ultimately, schools need to establish a culture that recognises the importance of skill development and places it on par with research. Education should not be merely about delivering information; it should also focus on building knowledge through both research and practical experiences, allowing all students to develop strong skill sets. Every graduate should be fluent in the Core Skills for 2030. Schools also need to reassess the job descriptions for teaching-focused faculty, moving away from the traditional requirement of a terminal degree, and instead focusing on what is truly necessary for success in these roles. This perspective should be ingrained in the culture, particularly among those involved in the hiring process.