Gross Domestic Product

Why Should I Care?

People need to know how big our economy is, and whether or not it is growing. If the economy is too small or growing too slowly, we may be in big trouble. This can affect the levels of employment and prosperity, but also the political stability of any country. Of course, growth also relates to environmental issues, and is the object of much criticism from environmentalists.

This Lecture Has 4 Parts

- What is GDP?

- Two kinds of GDP

- Potential Output

- Other Measures of Economic Accounting

What is Gross Domestic Product?

We know people have produced goods and traded them in and around cities for the past 10,000 years. But we have only recently measured our aggregate production since the end of the Second World War (1951 in Canada, 1945 in USA).

One reason for this is that it was too hard to even try this before modern technology such as calculators. Imagine taking inventory of everything produced in Montreal in one year, let alone Quebec or Canada. Millions of different products, multiplied by a multiplicity of ever-changing prices… A nightmare.

Another reason: it was not until John Maynard Keynes proposed the idea of Aggregate Demand – and wrote a formula to measure it – in 1936, that we had a formal idea of what to measure.

-

What is GDP?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the most widely used economic statistic. It represents a measurement of the monetary value of all of an economy’s production over a given period of time.

Gross means the number includes the total sales of the economy, before taking out particular accounts such as depreciation of physical capital (machine replacement due to wear).

Domestic means the number relates to production that takes place inside a state, province or country.

Product means the number relates to final goods and services.

GDP measures a flow of production, not stocks of product. It is designed to measure new production that was sold on a market. GDP is measured in dollars because it is a convenient common denominator. A shopping list of planes, architecture services, and oranges, just to name a few products, would be a nightmare to aggregate (to sum up).

Most of the data is collected from income and tax declarations sent to national agencies such as the Canadian Revenue Agency. This is survey data, which is aggregated and then sent to Statistics Canada, which calculates and publishes GDP figures. Once GDP statistics are produced, no one can trace back into the data to see who purchased what, or how rich someone is.

In Canada, GDP data is published at the end of every month, three months late. GDP includes only final products, to avoid double counting of inputs to production. A hammer is not included in GDP if it was purchased by a construction contractor who builds homes. The house will be included in GDP, as its price includes the cost of tools (hammers).

Money transfers between persons and sales of used products are also left out because they do not reflect new production.

-

Two kinds of GDP

There are two measurements of GDP, which follow the circular flow diagram. From this theory, economists deduct that incomes earned from resources must be equal to the sales of final goods and services. There are therefore two equal methods of calculating the size of the economy. They cannot be added to each other. That would be double-counting.

It is true of individuals. One person cannot (in logic) spend more money than they earn, and vice-versa. You cannot add their spending to their income to calculate the size of their economic activity. For example, if your income is $100,000 a year, your spending should be equal to that. But you are not worth $200,000!

GDP expenditure approach = GDP income approach

Spending on Goods & Services = Income from Resources

C + G + I + (X - M) = w + i + R + π + other incomes

Note - StatCan's new definitions

The formulas presented here are based on the traditional measurement of GDP. These categories are useful to understand the theoretical thinking behind the modelling.

However, there have been recent modifications to the classification of transactions in GDP. The following table shows the actual categories used by Statistics Canada for Expenditure-based GDP. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610022201

| Final consumption expenditure | |||

| Household final consumption expenditure | |||

| Goods | |||

| Durable goods | |||

| Semi-durable goods | |||

| Non-durable goods | |||

| Services | |||

| Non-profit institutions serving households' final consumption expenditure | |||

| General governments final consumption expenditure | |||

| Gross fixed capital formation | |||

| Business gross fixed capital formation | |||

| Residential structures | |||

| Non-residential structures, machinery and equipment | |||

| Non-residential structures | |||

| Machinery and equipment | |||

| Intellectual property products | |||

| Non-profit institutions serving households' gross fixed capital formation | |||

| General governments gross fixed capital formation | |||

| Investment in inventories | |||

| Of which: business investment in inventories | |||

| Non-farm | |||

| Farm | |||

| Exports of goods and services | |||

| Exports to other countries | |||

| Exports of goods to other countries | |||

| Exports of services to other countries | |||

| Exports to other provinces | |||

| Exports of goods to other provinces | |||

| Exports of services to other provinces | |||

| Less: imports of goods and services | |||

| Imports from other countries | |||

| Imports of goods from other countries | |||

| Imports of services from other countries | |||

| Imports from other provinces | |||

| Imports of goods from other provinces | |||

| Imports of services from other provinces | |||

Table - Expenditure-based definition of GDP

|

EXPENDITURE variables |

Description |

Definition |

Example |

|

C |

Personal consumption |

Consumer spending on goods and services |

milk |

|

G |

Government spending |

Buying goods and services |

military uniforms |

|

I |

Investment |

Buying physical capital |

Computers |

|

X |

Exports |

Foreigners buying domestic product |

Maple syrup, oil, airplanes, aluminum |

|

- M |

Imports |

Domestic spending on foreign goods |

Bananas, tv, dvd, iphone |

Table - Income-based definition of GDP

|

INCOME |

Description |

Definition |

Example |

|

W |

Wages |

Income from labour |

Salaries paid to workers |

|

i |

Interest |

Income from financial capital (loans) |

Interest paid on savings account |

|

R |

Rent |

Income from land, real estate |

Monthly revenue for apartment |

|

π |

Profit |

Income from private enterprise |

Restaurant Earnings after all costs are paid. |

|

O, t, D |

Other, taxes, Depreciation |

other sources, or costs to firms such as taxes and depreciation |

Farm revenues |

We see that wages make up the most of GDP on the income side. It should then not surprise anyone that consumption makes up the most of GDP on the spending side. On the expenditure side, almost all of the accounts have to do with goods and services. There is an exception: Investment.

However, do not confuse this type of macroeconomic investment with your personal portfolio of stocks and bonds. These are personal investments, and they are not included in GDP. In French, this is called placements. In macroeconomics, ‘Investment’ includes mostly expenditures on physical capital, such as machines, industrial buildings and residential housing.

To compare the wealth of countries of different sizes in all fairness, we use GDP per capita.

GPD per capita = GDP / population

Congo’s GDP is 35 billion US dollars (2016). Sounds like a lot of money. But Congo’s population is 64 million. That’s twice Canada’s. Once you divide the GDP by population, there’s only 444 dollars left per person in Congo. That is 100 times less than any Canadian province.

-

Potential Output

The GDP measure we have discussed is a measurement of real-life economic activity. If it rises, we are generally happy because more production means more stuff to make our lives more comfortable (hopefully not more junk), and more jobs so that everyone who wants a job can find one. Economists would like to be sure we don’t produce too much, because there is always a limit to our capacity of production. Economists also worry about not producing enough, because we wish to give everyone an equal opportunity to earn a living.

Economists want to compare GDP with a benchmark statistic that represents the level of production where all resources are used fully, without danger of over-heating. This level of production cannot be measured directly, as no one really knows what it is. It must be estimated, so there is some level of guess work here.

In Canada, potential output, or potential GDP, is estimated by many organizations such as the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), the Finance Department, the Bank of Canada, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The methods vary but they mostly come down to adding up the production capacity of our stocks of available labour and capital, such as machines, and natural resources. Of course, if we make more babies, if we have better education, if we attract more immigrants, and if we purchase better machines, our potential output will grow.

The big question is: are we producing more than potential?

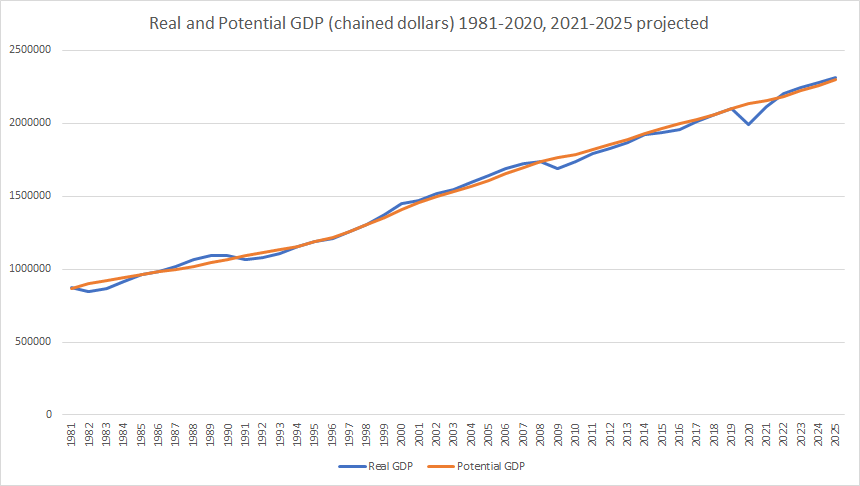

The answer is no, but almost. Since the end of the 2020-21 COVID 19 pandemic, Canadian production has recovered. During the pandemic, Canadian production decreased by 5.3 percent. It was one of the worst recessions since 2009, 1991, and 1981. Meanwhile, potential GDP kept growing because of demographic growth and improved technology. For 2020, production was worth 6.7 percent less than potential. That’s the largest output gap since 1981-1982, according to PBO figures. The good news is that the economy has come back to potential quickly. The PBO projects GDP to match potential as of 2021 through to 2025.

Graph – Potential GDP in Canada and the Output Gap

Source: PBO, 2020.

This chart was produced thanks to data from the PBO, but generally unavailable on the web. The graph clearly shows episodes of overheating in the late 1980’s, the early 1990’s (1998-2001), and the late aughts (2006-2008). During this time, Real GDP was above potential. The graph also shows episodes of recessions in the early 1980’s, the early 1990’s, and the late aughts (2009-2013).

The interesting thing on this graph is that we see that Potential GDP constantly increases. It is a moving target. This is because population size (births, immigration) and new technology (robots, software, machines) keep improving the production capacity of the economy. Full employment is only achieved when Real GDP is equal to potential. The consequence of this is that recoveries often take more time. Even if Real GDP increases, it may not outpace the rate of increase of Potential Real GDP, in order to fill in the gap.

We should mention three flaws about this statistic:

- Potential GDP is an estimate, and the technique used to produce the number may be up to debate.

- There are no Potential GDP figures for Canadian provinces.

- Potential GDP says nothing of planetary limits to growth

- Other Measures of Economic Accounting

The well-known GDP figures track spending by anyone, as long as they are on Canadian soil. Other measures do this differently. Gross National Product (GNP) is an older method which tracks the economic actions of Canadians both here and abroad. It excludes spending by foreigners in Canada.

GDP: size of the economy of Canada, whoever they are

= C + G + I + (X - M)

GNP: size of the economy of Canadians, where ever they are

= C + G + I

In the past, the level of trade between nations was much lower and GNP was the only measure of the economy. With added trade came the necessity to calculate GDP. Canada officially switched to GDP in 1986 but continues to calculate GNP.

The big difference between GDP and GNP is the inclusion of Net Exports in GDP. Because Net Exports are usually positive in Canada, GDP is thus usually larger than GNP in our country.

Shortcomings of GDP: excludes non-paid work, black-markets, happiness, distribution of wealth, social well-being, development of institutions. One statistic that can take many of these factors into account is the Human Development Index.

Green Policy

Overall, GDP does not include the notion of our ecological footprint. This footprint represents the cost for nature of the presence of human activity. Whether it be the fault of industry, consumers, or other institutions, our economy is having a toll on the natural environment.

As an individual, your ecological footprint represents the earth’s resources which are needed to supply you the things you consume during a whole year, including private goods and services such as food and entertainment, but also public goods such as protection, health care and education.

Not measuring our ecological footprint is a critical issue because most politicians base their success in terms of economic leadership on the growth of their GDP figure. GDP is therefore a misleading indicator for many reasons.

First, GDP does not consider the economic production of the earth itself: any production which is not sold through a market is de facto ignored by this measurement. Environmental services are the object of more recent research, such as the provision of clean air produced by trees, healthy fish caught by villagers, vegetables picked by gardeners, game hunted in the fall by both city and rural folk, plant medicines harvested by knowledgeable elders… These products are not bought, so they are not included in GDP.

If GDP were to drop suddenly, this means the market economy has contracted. This does not necessarily mean that the overall economy has contracted. Of course, it is almost impossible to count, and collate the data of aggregate measurements of the non-monetized economy. While money transactions leave a paper trail, barter and self-production do not.

Second, many products counted in GDP are very polluting and actually create debt for future generations in terms of depleted resources, decreased natural productions, and clean-up costs. These issues are not accounted for in GDP. Usually, when you work more, you hope it makes you wealthier. But there are cases where if a country works more, and its GDP increases, it will actually become poorer because of the debt that is contracted between human society and the natural environment.

Green data for GDP exists, in theory. Many countries have tested the idea of producing an aggregate production measurement, which accounts for and deducts environmental capacities. The USA, India, and China, have actually worked on a variety of measurements over the last 30 years. All of them abandoned these projects because they showed that their countries’ GDP growth shrinks dramatically, or even becomes nil, when the environmental quantities are brought into account.

Third, GDP is a flow statistic, and does not take into account the depletion of upstream stocks of resources, and the downstream stocks of goods. Many products we buy are programmed to become obsolete quickly, which means we need to artificially increase flows to keep consumer stocks steady. A more durable approach to consumer goods would reduce GDP and reduce our imposition on upstream stocks of resources.

Many organizations wish to report on their activities including their ecological footprint. To find out how to report data, any organization can follow the standards developed by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), an independent organization which is also a collaborating centre of the United Nations Environment Programme.

Climate Change Solution

GDP is not designed to measure the production of most GHGs, since they are not sold on a market. However, GHGs can be measured by their weight and volume. If we can track and measure the emissions, we can manage the emissions. A kilogram of carbon has the same greenhouse effect on the atmosphere, no matter the type of gas, or the location it was emitted from.

The problem is that some countries emit way more than others, such as Canada. Of course, the reason we emit so much is that much of our economy depends on fossil fuel energy. Massive investments are needed to reduce our dependence on oil and gas without reducing our economic production. How can we solve Climate Change without hurting GDP?

Let’s start with some data. One source is the Green Growth webpage of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD publishes many statistics which cross economic and environmental data.

For example, you can track the evolution of what the OECD calls “Production-based CO2 productivity” across countries. This is the ratio of GDP in US$, per kg of energy-related CO2 emissions. The top country in this dataset was Switzerland, with 15.78 $ per kg. This means that their GDP needs very little carbon. Switzerland’s economy is based on services such as banking and tourism, which can run on renewables.

Canada is at the bottom of the dataset, with a very low figure, at 3.00 $/kg in 2018. This means we need a lot of carbon to produce each dollar of our GDP. Canada is actually the fourth largest petroleum producer in the world, generating 5.5 billion barrels per day in 2019. Most of that oil comes from the Western Oil Sands, which happen to be the most polluting oil sources in the world. Canadian leadership needs to understand that our fixation on GDP is contributing to warming the planet.

Democracy Booster

What can regular people do about it? Sure, it’s hard to raise millions of dollars to fund green energy projects across the country. It’s hard to convince capitalists on Toronto’s Bay Street that oil is a bad thing, when oil has made Canada a wealthy country.

This said, regular people can do several things.

- Calculate your personal household carbon footprint. Plan your transition by making smart choices, and save money!

- Change your consumption habits away from plastics, fast fashion, airplane travel, cruise ships, and gasoline vehicles.

- Invest your savings in carbon-free securities. If you have a company pension plan, you can urge the investment managers to divest from oil producers, and invest in carbon-free companies.

- Vote for political parties at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels, who run on a plan to create jobs while transitioning the country out of carbon energy.

- Convince your local organizations, such as your school, your tennis club, or your hockey team to calculate their carbon footprint.

Let’s remember that many people’s livelihoods depend on the carbon economy, especially in Canada, and especially in certain parts of the country, such as Alberta and Newfoundland. No one should be left out to dry. However, let’s also remember that Canadians are not more important on this Earth than other humans, or other plants and creatures. Our daily lifestyle choices should not be putting the well-being of people and natural life at risk in other parts of the globe.

Wrap-Up

GDP is based on the spending aggregate Keynes invented in 1936. It is the most widely used economic statistic today. It is produced by Statistics Canada, and made public every month, three months late.

Statistics Canada also calculates the income version of GDP to make sure it balances out with expenditures (spending). It’s also nice to have as much data as possible to track different trends.

Once you have GDP, you can calculate GDP per capita to fairly compare the size of economies between countries. GDP is imperfect. Other measures include GNP and the Human Development Index.

Cheat Sheet

Gross Domestic Product:

A measurement of the monetary value of an economy’s production over a period of time.

Potential Output:

An estimate of an economy’s capacity to produce, if all resources are used at full use.

Gross National Product:

A measurement of an economy based on the nationality of the subjects, which does not account for trade.

Statistics Canada:

Our federal data collection agency.

GDP per capita:

A measure of wealth that can be used to compare countries.

References and Further Reading

Barnett, R. & Matier, C. (2010). Estimates of Canada’s Potential GDP and Output Gap – A Comparative Analysis. Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Parliament of Canada. Web. www.parl.gc.ca/PBO-DPB/documents/Potential_GDP.pdf

Bartlett, R. Cameron, S. & Lao, H. (2014). Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2014. Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Parliament of Canada. Web. http://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/files/files/EFO2014_EN.pdf

Carbon Footprint Ltd. (2020). Carbon Calculator. https://www.carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx

OECD. (2020). Green Growth Indicators: Headline Indicators. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Web. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=GREEN_GROWTH

Sheehan, B. (2009) Understanding Keynes' General Theory. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

US Energy Information Administration. (2019). International Data Rankings. United States Government. Retrieved from web. https://www.eia.gov/international/overview/world

Xiaohua, S. (2007). Call for return to green accounting. China Daily. Web. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/200704/19/content_853917.htm