How to Build Knowledge Scientifically?

Why Should I Care?

How research is conducted can affect the results of a scientific project. It is important to understand the "how" of the scientific method, since so much knowledge is derived from science. You have heard the saying, “The Devil is in the details.” Understanding how science is done, and how it has evolved throughout history, allows one to better understand the role of science in society.

This lesson has 4 parts

- Definitions

- Objects of observation

- History of Science

- What is the Research Process?

How to Build Knowledge Scientifically?

paragraph

video here

-

Part 1

paragraph

Collapsible Block

-

Part 2

paragraph

-

Part 3

paragraph

Definitions

Variable:

Any aspect or characteristic that varies from case to case, or over time.

Empirical data:

Data are sets of observations that were obtained from natural life. Empirical means that the data is not artificial or hypothetical.

Anecdotal data:

One or very few observations will be considered an anecdote, or anecdotal. Scientists won't base knowledge on small sample data sets.

Hypothesis:

A statement that focuses on the possible relationships between variables, expressed in a way that involves testing through observation.

Theory:

A logically coherent set of ideas that accounts for the empirical patterns discovered by empirical research.

Objects of Observation

Most variables measured in a social science research study would fall into the following categories. This is what scientists measure when they are

Personal Characteristic: height, skin color, eye color, shoe size, etc.

Socio-Demographic Characteristic: religion, gender, age, language, income, etc.

Opinion: political, hockey, moral, legal, cultural, artistic

Motivations: interests, goals, objectives, influences

Ideology: schools of thought, political parties, philosophies

Biases / Prejudice: culture, education, prior experience

Preferences: taste, needs, wants, cultural preferences

Personality: outgoing, resentful, loyal, personal values, upringing and grooming.

Personal History / Background: events, people, deaths, immigration

Family Dynamics: rank in the family, role, age, etc.

Cultural History: events, people, history class, family politics

Perception / Self-Perception: how you are perceived, how you perceive yourself

Aptitude /Ability: running, jumping, typing, reading, speaking, calculating, etc.

Behaviour: actions, verbal, non-verbal.

Intention: honesty, lying, mischief, morality.

Action: cowardice, bravery, brazenness, audacity, etc.

Level of Knowledge: test, quiz, recall, response time, memory.

History of Science

Science is a rather young development in human history. The scientific method, as applied in university research, really took off in the 18th century AD. This is not that long ago, if you consider that agriculture and cities appeared in about 8,000 years BCE.

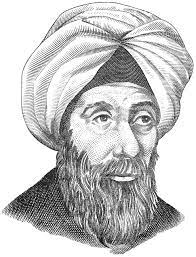

However, there are debates as to which thinkers were the first scientists, such as Aristotle, who is credited with breakthrough studies in biology (Lo Presti, 2014). According to Harris (2020), "many experts recognize Ibn al-Haytham, who lived in present-day Iraq between 965 and 1039 C.E., as the first scientist. He invented the pinhole camera, discovered the laws of refraction and studied a number of natural phenomena, such as rainbows and eclipses."

Ibn al-Haytham: The First Scientist

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ibn_al-Haytham

During this period, the Arab world produced many innovations, such as the invention of algebra.

In terms of developing a very rigorous scientific method, many look to William Gilbert, a lesser-known British scientist credited with discoveries in magnetism. His work was extremely meticulous in his experiments, which set the bar for design and methodology in science. De Magnete was published in 1600, more than four centuries ago.

William Gilbert: The Father of Rigorous Methodology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Gilbert_%28physician%29#/media/File:William_Gilbert_45626i.jpg

The question of whether or not a thinker was a scientist is mostly a question of methods. Did they use hypothesis testing and observations? Or did they use arguments? If they used arguments, like Thales in Ancient Greece, then they aren't considered true scientists.

Another point of contention is over the creation of the first university, which will accelerate the use of the scientific method. According to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the University of Al-Karaouine (also written as Al-Quaraouiyine and Al-Qarawiyyin) was founded in 859 AD and is "considered by UNESCO and the Guinness Book of World Records to be the oldest continually operating university in the world." The university was established at the very beginnings of Morocco’s oldest imperial city, Fez, which speaks to the utility of education and science to the development of cities (Griffiths & Buttery, 2018).

Al-Karaouine: The Oldest University

In Europe, the oldest, and still operating, university seems to be that of Bologna, Italy, which started as a law school in the year 1180 (Verger, 2003). This said, these were rocky times. During the medieval period, religious zealots burned many libraries on the continent. Thanks to Irish monks, the written works dating back to Ancient Greece and Rome had been transcribed and protected on the Éire Island, naturally isolated by the sea (Cahill, 1996).

Elements at the heart of science from its beginnings

The scientific method has evolved over the centuries since it first began to be developed by the early scientists. Still, to this day, the scientific method is beholden to three core elements: transparency, logic, and repeatability.

Transparency relates to the author's openness to share what they learned, and not to keep it private for personal gain. Much research is done in private today, in corporate laboratories for example. However, university scientists are encouraged to share their results publicly, and without charge, usually through academic publishing. Transparency also relates to how the data was collected. Scientists should be open to explain their methods, and instruments. Nowadays, quantitative datasets are made available online, for any reader who wishes to review, or even try to duplicate results on their own computer.

Logic relates to the fact that scientific explanations of any phenomena must be rooted in some kind of reason. We don't allow scientists to explain something away using the powers of the supernatural, for instance. In this case, logic does not refer to using only arguments. One needs to provide empirical evidence, observations, to confirm their hypothesis. But the explanation must rooted in logic.

Repeatability relates to scientists who copy or replicate someone's study to verify that the results still stand. This is especially important when a scientist has found an unlikely and surprising result. Other scientists will try to replicate the study on a new sample, in very similar conditions, to add weight to the findings and conclusions.

What is the Research Process?

There are 8 steps to the research process.

Step 1: Choose a topic 5 W

Step 2: Review the literature What do we know / ignore?

Step 3: Formulate the problem Question or Hypothesis

Step 4: Organize research design Pick and Create the instrument

Step 5: Gather data Observe and Record

Step 6: Analyze data Crunch the numbers, facts

Step 7: Interpret data Compare to flaws, caveats

Step 8: Communicate results Write article, conference

Formal theories are used to build steps 1, 2, 3 and 4. The latter steps aim to verify the validity of the theories with empirical data. Read Del Balso & Lewis, First Steps (2011), for more information on this.

What are the Data Collection Methods? |

What are Data Collection Tools? |

| Survey | Questionnaire / Interview |

| Experiment | Laboratory / Questionnaire / Interview / Recordings |

| Field Work | Recordings / Interview / Artifacts |

| Unobtrusive Measurement | Recordings / Artifacts |

| Content Analysis | Documentation / Media |

|

Available Data |

How Research Begins

Research does not begin in the lab, or in a fieldwork activity. It might begin with a newspaper clipping, a conversation with a colleague, a movie, a book, an observation as a parent, a conversation with your grand-father, etc…

Personal experience – Nazi Germany, Racial Discrimination, Family Environment, etc. may lead some people who suffered these events to study these topics as researchers.

However, personal experience can also bias your approach. You may misinterpret the ideas and opinions of people that have another age, gender, ethnicity, mother tongue, income, social class, education, etc.

Values of Modern Research

Objectivity: gathering data honestly, even if discoveries contradict cherished personal beliefs

Empirical Verification: research does not depend on personal experience, intuition, faith in authority, or tradition to provide answers to their questions.

Cooperation: science builds on past research (for free) and lays the foundation of future research (for free). Scientists work together on science (for free).

Transparency of Method: communicate method and results clearly, honestly, and in enough detail that other researchers can fully understand how the research was carried out, and the data interpreted.

References and Further Readings

Bouma, G. D., Ling, R. & Wilkinson, L. (2012) The Research Process. Oxford University Press.

Cahill, T. (1996). How the Irish Saved Civilization, The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. Penguin Random House.

Del Balso, M. & Lewis, A. (2011). First Steps: A Guide To Social Research. Nelson.

Griffiths, C. & Buttery, T. (2018) The world's oldest centre of learning. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20180318-the-worlds-oldest-centre-of-learning

Harris, W. (2020). Who Was the First Scientist? HowStuffWorks.com Web. https://science.howstuffworks.com/first-scientist.htm

Lo Presti, R. (2014). History of science: The first scientist. Nature. Volume 512, pages 250–251. https://www.nature.com/articles/512250a

Verger, J. (2003). Universities in the Middle Ages, in Hilde de Ridder-Symoens; Walter Rüegg (eds.). Patterns. A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press. p. 48.