How to Build Knowledge Scientifically?

Why Should I Care?

How research is conducted can affect the results of a scientific project. It is important to understand the "how" of the scientific method, since so much knowledge is derived from science. Understanding how science is done, and how it has evolved throughout history, allows one to better understand the role of science in society.

This lesson has 4 parts

- Definitions

- Objects of observation

- History of Science

- What is the Research Process?

How to Build Knowledge Scientifically?

paragraph

video here

-

Definitions

Observation

An event, an aspect, a behavior, or other phenomenon, which is recorded for analysis. What is noted, written, seen, heard, felt, smelled, or otherwise observed. Ex: the colour blue is an observation of eye colour.

Case

The case is an identifier that binds many variables to the same object. In social science, a person is usually the case associated to a set of variables being observed. For example, if you are studying eye colour and height, both of these variables would be recorded from each person, from each case. Cases can be numbered or named so that we can associate their set of observed variables. In a large sample, each case would have a number. Cases can also be an animal, a plant, an organization, a group, or any other type of object being observed for many characteristics.

Variable

Any aspect or characteristic that varies from case to case, or over time. Ex: eye colour in humans varies from person to person (cases). Height in humans varies both across cases, and over time.

Empirical data

Data are sets of observations that were obtained from natural life. Empirical means that the data is not artificial or hypothetical.

Anecdotal data

One or very few observations will be considered an anecdote, or anecdotal. Scientists won't base generalizations on small sample data sets. Ex: an observation is made of one child screaming. Scientists won't generalize that many, most, or all children scream.

Hypothesis

A statement that focuses on the possible relationships between variables, expressed in a way that involves testing through observation. Ex: extroversion in personality may be associated to certain occupations, such as stage performance.

Theory

A logically coherent set of ideas that accounts for the empirical patterns discovered by empirical research. Theory is not a synonym of hypothesis. It is rather the whole set of knowledge, including observations and testing for hypotheses, over some time, about a topic. Ex: Economic theory would predict that lower prices be associated to increased demand for good or service.

-

Objects of observation

Observations are often categorized as variables, using some kind of metric or unit of measurement. For example, a simple dataset would be measuring body weight in kilograms. It is a daunting task to list all of the variables ever used in social science. However, to give you a sense of what's possible for scientists to observe, here is a list of groups of variables. Some disciplines will be more interested in certain variables, for example, political scientists will be interested in ideology. However, any scientist can include any variable they wish to measure, often times to compare with other variables being studied.

The following list includes categories in bold, with examples of variables. For each example, imagine how you would measure the variable. In some cases it would be a numerical value, in other cases, it would be a quality. Ex: Shoe size would be 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, etc.

Personal Characteristic

height, skin colour, eye colour, shoe size

Socio-Demographic Characteristic

religion, gender, age, language, income, etc.

Opinion

political, hockey, moral, legal, cultural, artistic

Motivations

interests, goals, objectives, influences

Ideology

schools of thought, political parties, philosophies

Biases / Prejudice

culture, education, prior experience

Preferences

taste, needs, wants, cultural preferences

Personality

outgoing, resentful, loyal, personal values, upringing and grooming

Personal History / Background

events, people, deaths, immigration

Family Dynamics

rank in the family, role, age

Cultural History

events, people, history class, family politics

Perception / Self-Perception

how you are perceived, how you perceive yourself

Aptitude /Ability

running, jumping, typing, reading, speaking, calculating

Behaviour

actions, verbal, non-verbal

Intention

honesty, lying, mischief, morality

Action

cowardice, bravery, brazenness, audacity

Level of Knowledge

test, quiz, recall, response time, memory

-

History of Science

Science is a rather young development in human history. The scientific method, as applied in university research, really took off in the 18th century AD. This is not that long ago, if you consider that agriculture and cities appeared in about 8,000 years BCE.

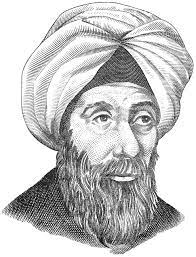

However, there are debates as to which thinkers were the first scientists, such as Aristotle, who is credited with breakthrough studies in biology (Lo Presti, 2014). According to Harris (2020), "many experts recognize Ibn al-Haytham, who lived in present-day Iraq between 965 and 1039 C.E., as the first scientist. He invented the pinhole camera, discovered the laws of refraction and studied a number of natural phenomena, such as rainbows and eclipses."

Ibn al-Haytham: The First Scientist

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ibn_al-Haytham

During this period, the Arab world produced many innovations, such as the inventions of algorithms, and algebra.

In terms of developing a very rigorous scientific method, many look to William Gilbert, a lesser-known British scientist credited with discoveries in magnetism. His work was extremely meticulous in his experiments, which set the bar for design and methodology in science. De Magnete was published in 1600, more than four centuries ago.

William Gilbert: The Father of Rigorous Methodology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Gilbert_%28physician%29#/media/File:William_Gilbert_45626i.jpg

The question of whether or not a thinker was a scientist is mostly a question of methods. Did they use hypothesis testing and observations? Or did they use arguments? If they used arguments, like Thales in Ancient Greece, then they aren't considered true scientists.

Another point of contention is over the creation of the first university, which will accelerate the use of the scientific method. According to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the University of Al-Karaouine (also written as Al-Quaraouiyine and Al-Qarawiyyin) was founded in 859 AD and is "considered by UNESCO and the Guinness Book of World Records to be the oldest continually operating university in the world." The university was established at the very beginnings of Morocco’s oldest imperial city, Fez, which speaks to the utility of education and science to the development of cities (Griffiths & Buttery, 2018).

Al-Karaouine: The Oldest University

In Europe, the oldest, and still operating, university seems to be that of Bologna, Italy, which started as a law school in the year 1180 (Verger, 2003). This said, these were rocky times. During the medieval period, religious zealots burned many libraries on the European continent. Thanks to Irish monks, the written works dating back to Ancient Greece and Rome had been transcribed and protected on the Éire Island, naturally isolated by the sea (Cahill, 1996). Once the renaissance period started, continental Europeans were very happy to be able to build on the rich wealth of knowledge that the Irish monks had preserved.

Elements at the heart of science from its beginnings

The scientific method has evolved over the centuries since it first began to be developed by the early scientists. Still, to this day, the scientific method is beholden to three core elements: transparency, logic, and repeatability.

Transparency relates to the author's openness to share what they learned, and not to keep it private for personal gain. Much research is done in private today, in corporate laboratories for example. However, university scientists are encouraged to share their results publicly, and without charge, usually through academic publishing. Transparency also relates to how the data was collected. Scientists should be open to explain their methods, and instruments. Nowadays, quantitative datasets are made available online, for any reader who wishes to review, or even try to duplicate results on their own computer.

Logic relates to the fact that scientific explanations of any phenomena must be rooted in some kind of reason. We don't allow scientists to explain something away using the powers of the supernatural, for instance. In this case, logic does not refer to using only arguments. One needs to provide empirical evidence, observations, to confirm their hypothesis. But the explanation must rooted in logic. A scientist cannot delegate the explanation to a God or the Divine.

Repeatability refers to the practice of repeating experiments and studies to see if the results vary. This is especially important when a scientist has found an unlikely and surprising result. Other scientists will try to replicate the study on a new sample, in very similar conditions, to add weight to the findings and conclusions. If the result is not replicable, then the initial study loses its importance. If the initial result replicates many times, it becomes part of scientific theory.

-

What is the Research Process?

The scientific research process has seven important steps. They don't always need to be in this order, but most research projects operate this way.

Seven Steps of the Scientific Process

Step 1 - Choose a topic

Using the 5 Ws, who, what, when, where, why, and how, find a topic that needs to be researched. It may be a popular social issue, such as drug addiction, which is a big problem, or a more technical issue, concerning a specialized area of a scientific discipline, such as the sensitivity of monetary policy in economics.

Step 2 - Review the literature

This allows the researcher to decide on the aim of the research. Once you know which studies have come out recently, and where the scientific community is headed, you can decide on what you want to contribute.

Step 3 - Formulate the problem

This step is necessary to single out an issue you want to research in more detail. Do you wish to replicate results from another study, which you find surprising? Do you wish to start a new vein of research which has been avoided or ignored by others? Do you wish to compare results using different methodologies? Once you answer those questions, you can start writing a detailed research question and a set of hypotheses you can test with data.

Step 4 - Design the method

Pick and create the instruments that make up your method for observing new data. Are you going to use a laboratory experiment? Would you prefer to run a survey? Do field work? Is this data going to be extracted from living people or from objects that don't speak?

Step 5 - Gather data

Observe and record. This step relates to the gathering of new observations. This is original data that will contribute to the body of literature on this topic.

Step 6 - Analyze and Interpret data

In this step, the scientist looks for patterns in the data. Are there types of observations that are more frequent? Is it possible to qualify the observations, using terms like fast/slow, high/low, heavy/light, etc. ?

Step 7 - Communicate results

The scientist now needs to write an article for publication in a scientific journal. The submission will be reviewed by a blind committee of peers who don't know the identity of the author. The scientist can also participate in conferences, and present their findings to colleagues.

How Research Begins

Research does not begin in the lab, or in a fieldwork activity. It might begin with someone sitting at home, reading the newspaper. It might start with a conversation with a colleague, after one watches a movie, reads a book, makes an observation as a parent, or chats with their grand-father.

Research can begin anywhere. Think of personal experiences. Maybe your family has history with Nazi Germany, that might bring about family discussions, or a collection of objects, which can become the basis to start a research project.

Values of Modern Research

The process of scientific research depends heavily on the honesty and integrity of the scientists who publish studies. We identify four important values that allow for this research process to be as pure, ethically, as possible.

Objectivity

To gather data honestly, even if discoveries contradict cherished personal beliefs, or personal interests

Empirical Verification

Without data to confirm an idea, the scientific process is stalled. Science cannot depend on personal experience, intuition, faith in authority, or tradition to provide answers to research questions.

Cooperation

Science builds on past research made available for free, and lays the foundation of future research without charge. Scientists work together on science. There may be competition, in terms of attaining a scientific result first. However, this does change the way studies and research methods are shared, which is cooperatively. Research done for private corporations is not shared publically. It is rather kept as industrial secret for the benefit of the corporation.

Transparency of Method

Communicate method and results clearly, honestly, and in enough detail that other researchers can fully understand how the research was carried out, and how the data was interpreted.

References and Further Readings

Bouma, G. D., Ling, R. & Wilkinson, L. (2012) The Research Process. Oxford University Press.

Cahill, T. (1996). How the Irish Saved Civilization, The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. Penguin Random House.

Del Balso, M. & Lewis, A. (2011). First Steps: A Guide To Social Research. Nelson.

Griffiths, C. & Buttery, T. (2018) The world's oldest centre of learning. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20180318-the-worlds-oldest-centre-of-learning

Harris, W. (2020). Who Was the First Scientist? HowStuffWorks.com Web. https://science.howstuffworks.com/first-scientist.htm

Lo Presti, R. (2014). History of science: The first scientist. Nature. Volume 512, pages 250–251. https://www.nature.com/articles/512250a

Verger, J. (2003). Universities in the Middle Ages, in Hilde de Ridder-Symoens; Walter Rüegg (eds.). Patterns. A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press. p. 48.