Theories of Leadership

Early Trait Approach

From the turn of the century until the 1940s, most leadership studies focused on the personality traits of individuals that made them leaders and not followers. Thomas Carlyle set the stage for the great man theory, and other researchers followed suit, trying to determine what kind of traits made a great leader great.

Francis Galton, an English scientist and researcher, wrote a book Hereditary Genius in 1869, which was the first social scientific attempt to study genius and greatness (Galton, 1869). To determine if human ability was hereditary, he chose “eminent” men (men who exhibited extraordinary leadership qualities) and counted the relatives to see how many additional “eminent” men were in their background. Galton hypothesized that there would be a higher percentage of “eminent” men in their lineage than in the general population. His testing (for which he invented methods of historiometry) showed that numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when going from first degree to second degree relatives, and from second to third. He took this as evidence of the inheritance of abilities.

As you might guess, even Galton recognized the limitations of these studies. He went on to study twins and adopted children, testing the “nature vs. nurture” term that he’d coined, but never strayed too far from the idea that qualities were inherited instead of taught.

In the early 1900s, American psychologist (and, like Galton, a eugenicist) Lewis Terman studied gifted children, and he conducted a variety of studies on the children and their parents to reinforce the idea of inheritance of abilities. And in the July, 1928 issue of The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, researcher W.H. Cowley wrote,

The approach to the study of leadership usually has been and perhaps always must be through the study of traits. Leadership obviously is not a simple trait but rather a complex of main traits fashioned together as a unity. An adequate appraisal of leadership would reduce this complex to its individual units, and any study of leadership to be of value should produce a list of traits which go together to make the leader. (Cowley 1928)

In 1948, after years of experiments and studies, researcher Ralph Stogdill determined that leadership exists between persons in a social situation, and that persons who are leaders in one situation may not necessarily be leaders in other situations (Stogdill, 1948). This marked the end of researchers’ tenacious ideas that individual differences characterized leadership, or that they’d be able to predict leadership effectiveness. In the next sections, we’ll talk about the behavioral and contingency approaches these new theories sparked. But we have to acknowledge here that this wasn’t the end of studying traits in leadership. The trait approach wasn’t done—it just took a break.

Looking at Trait Theory Today

So, if studying leadership traits isn’t useful, why are we talking about it? Well, surprisingly, interest in the topic continues, supported by media and general public opinion. Think about how media describes business leaders like Mary Barra and Bill Gates. They’re innovative. They make tough decisions. They’re philanthropic. The media is constantly throwing their personality traits out there for us to digest.

Twelve percent of all the research published on the topic of leadership between 1990 and 2004 contains the keywords “personality” and “leadership.” Interest persists, and new information has been uncovered. Researcher Steven J. Zaccaro pointed out that, even in Stogdill’s argument against traits, his studies contained conclusions suggesting that individual differences can still predict leader effectiveness.

Remember that Cowley wrote that traits collectively lent themselves to leadership effectiveness. Taking a page from this book, Zaccaro and colleagues developed the trait-leadership model that attempted to address traits and their influence on a leader’s effectiveness. The premise of the Trait-Leadership Model (Zaccaro, Kemp, Bader, 2004) is that (a) leadership emerges from the combined influence of multiple traits (integrated, rather than individual, traits) and (b) leader traits differ in their proximal influence on leadership.

Zaccaro’s model looks like this:

This model comes with a list of leader traits, which Zaccaro reminds us are always not exhaustive. But traits based on his 2004 model include extraversion, agreeableness, openness, neuroticism, creativity, and others.

Two other models have emerged in recent trait leadership studies. The Leader Trait Emergency Effectiveness Model, created by researcher Timothy Judge and colleagues, combines behavioral genetics and evolutionary psychology theories of how traits are developed and puts them into a model that attempts to explain leader emergence and effectiveness. A second model, the Integrated Model of Leader Traits, Behaviors, and Effectiveness, created by D. S. Derue and colleagues, combines traits and behaviors in predicting leader effectiveness and tested the mediation effect of leader behaviors on the relationship between leader traits and effectiveness.

In spite of the increased focus of researchers on trait theory, it remains among the more criticized theories of leadership. Some argue it’s too simplistic. Others criticize that it studies leadership effectiveness as it’s perceived by followers, rather than actual leadership effectiveness. But we want to leave you with two thoughts on the trait approach before we move on:

- Traits can predict leadership. Years ago the evidence suggested otherwise, but the presence of proper framework for classifying and organizing traits now help us understand this better.

- Traits do a better job of predicting the emergence of leaders and the appearance of leadership than they do distinguishing between effective and ineffective leadership.

Stogdill’s comments encouraged researchers to look in other directions back in the late 1940s. If it’s not the personality traits that predict effective leadership, perhaps it’s the behavior of those leaders we should be studying. Let’s take a look at the behavioral approach to leadership next.

Behavioural Approach

Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid

In 1964, researchers Robert Blake and Jane Moutin introduced their managerial grid as a graphic portrayal of a two-dimensional view of leadership.[3]

Like the Ohio State and University of Michigan studies, Blake and Mouton concentrated on concern for production and concern for people. They scored each of those areas on a scale of 1 (low) to 9 (high) to create 81 different positions in which the leader’s style might fall. The result was five different types of behavioral styles.

- In the accommodating management style, leaders yield and comply. They pay attention to the comfort of the employees in hopes that they’ll be productive. This style often results in happy employees but is not necessarily productive.

- In the indifferent management style, leaders evade and elude. They don’t give much consideration to people or production, and try to fly under the radar a bit without getting into trouble.

- In the sound management style, leaders contribute and commit. They pay high attention to both people and production and encourage teamwork and commitment. It’s very Theory Y!

- In the dictatorial management style, leaders control and dominate. They pay attention to production but not to people, and use rules and punishment to achieve goals. It’s very Theory X!

- In the status quo management style, leaders balance and compromise. They are middle-of-the-road, and as a result, people needs and production needs aren’t necessarily met.

Managers performed best when they scored in the “sound” area. But the grid offered better framework for conceptualizing leadership style rather than presenting any new information in clarifying leadership behaviors, because there’s very little substantive evidence to support the conclusion that a sound style is most effective in all situations.

The Scandinavian Studies

We’re going to fast forward a few years to the 1990s, when Scandinavian researchers Ekvall and Arvonen began to reassess the idea that there were only two dimensions that captured the essence of leadership behavior.[4] In a changing world, they decided, leaders would exhibit development-oriented behavior. By exhibiting development-oriented behavior, these leaders would value experimentation, seek out new ideas and generate and implement change.

In their review of the Ohio State studies, Ekvall and Arvonen found that the researchers had identified behaviors such as “pushes new ways of doing things” and “encourages employees to do new things,” but those items didn’t explain much about leadership in 1940s, when those behaviors didn’t have as great an impact. Their studies indicate that just concentrating on two different dimensions of behavior may not be adequate to capture leadership in the twenty-first century.

Behavioral theories had modest success in identifying consistent relationships between leadership behavior and group performance. But none of these consider situation as a factor. Would Ralph Nader have been as successful a consumer activist if he’d been in Nicaragua and not the United States? Would Franklin Delano Roosevelt have been as successful leading the nation through the Revolutionary or the Civil Wars? None of these behavioral theories could clarify these situational differences. So, as we continued to grow in our theories of leadership, we started to look at contingency theories—theories that considered the leader and the situation

Contingency Approach

We know that traits and behaviors both have an impact on a leader’s success, but what about situation? This is the contingency approach. Circumstances might lead to peers and followers shunning a particular leader, and then seeing him or her in a different way later on. Since the 1960s, the guiding light for research has been the assumption that what makes a leader great depends on the situation.

The failure of researchers to arrive at any consistent results around leadership in the mid-twentieth center led to the study of situational influence. As they started to realize that a certain style and set of skills was appropriate for one situation and failed in another, they sought to determine which conditions matched which styles and skills. This led to several theories on isolating key situational variables, and we’ll look at a few of those now.

Fiedler Model

Fred Fiedler developed the first comprehensive contingency model for leadership and proposed that effective group performance depended on a solid match between the leader’s style and the degree to which the situation gives control to the leader.[1]

Fiedler started his study by determining whether a leader was more task oriented or relationship oriented in his or her behavioral traits. He determined to measure the leader’s propensity to one trait or another by developing the least preferred coworker questionnaire (LPC). The least preferred coworker asked leaders to react to sixteen sets of contrasting adjectives that would describe their least preferred coworker. LPCs respondents that described their least preferred coworker in relatively positive terms, it stood to reason that the leader employed a relationship based approach. Those that described their least favorite coworker unfavorably were deemed to be more task oriented.

It’s worth noting that about sixteen percent of those taking the evaluation scored right in the middle and fall outside the predictions of this theory. So the rest of our discussion concentrates on that 84% of respondents that took one side or the other.

At this point, Fiedler sought to define situations by which to compare these results. He did, in fact, identify three contingency dimensions that he was convinced defined the key situation factors that determine leadership effectiveness. Those situations were

- Leader-member relations: the degree to which members have confidence and trust in their leader (good or poor).

- Task structure: the degree to which job assignments are proceduralized (high or low).

- Position power: the degree of influence a leader has over power variables, such as hiring, firing, discipline, promotions and salary increases (strong or weak).

Fiedler then started comparing task-oriented and relationship-oriented leaders and their performances, based on the twenty-four possible combinations of the situations above, and this was the result:

Fiedler concluded that task oriented leaders tended to perform better when situations were very favorable or very unfavorable to them. Relationship oriented leaders perform better when situations are moderately favorable. Fiedler then modified his conclusions to state that task oriented leaders performed better in situations of high or low control, while relationship oriented leaders performed better in situations of moderate control.

While there are problems with the LPC evaluation and studies show that respondents’ scores are not stable, there is considerable evidence to support Fiedler’s conclusions. Still, it’s often difficult in practice to determine the quality of leader-member relations, the structure of task and how much position power the leader possesses.

Cognitive Resource Theory

More recently, Fiedler and an associate, Joe Garcia, reconceptualized Fiedler’s original theory, this time focusing on the role of stress as a form of situational unfavorableness and how a leader’s intelligence and experience influence his or her reaction to it.[2]

Essentially, Fiedler and Garcia propose that it’s difficult for leaders to think logically or analytically when they’re under stress, and how their intelligence and experience impacts their effectiveness in low- and high-stress situations. In other words, bright individuals perform worse in stressful situations, and experienced people perform worse in low-stress situations. This theory is garnering solid research support.

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Theory

The term “situational leadership” is most commonly derived from and connected with Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Theory. This approach to leadership suggests the need to match two key elements appropriately: the leader’s leadership style and the followers’ maturity or preparedness levels.

The theory identifies four main leadership approaches:

- Telling: Directive and authoritative approach. The leader makes decisions and tells employees what to do.

- Selling: The leader is still the decision maker, but they communicate and work to persuade the employees rather than simply directing them.

- Participating: The leader works with the team members to make decisions together. They support and encourage the team members and are more democratic.

- Delegating: The leader assigns decision-making responsibility to team members but oversees their work.

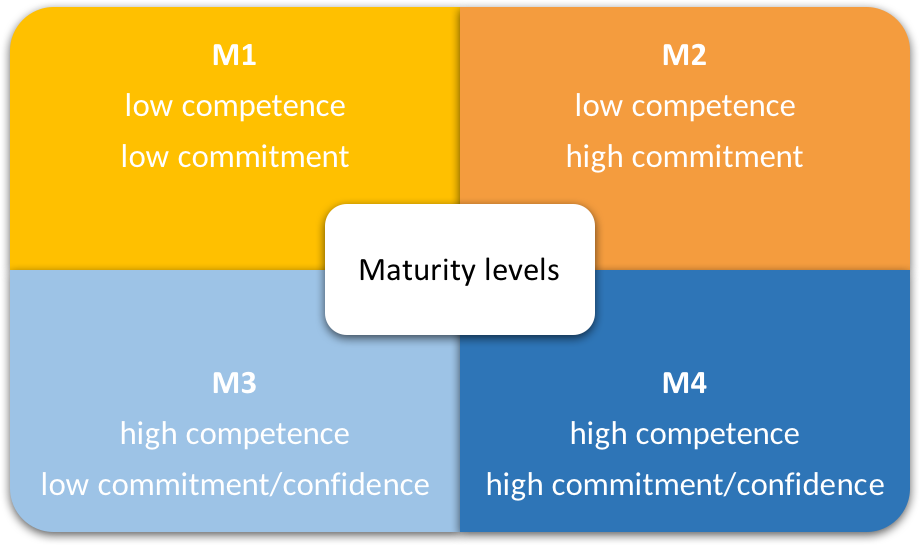

In addition to these four approaches to leadership, there are also four levels of follower maturity:

- Level M1: Followers have low competence and low commitment.

- Level M2: Followers have low competence, but high commitment.

- Level M3: Followers have high competence, but low commitment and confidence.

- Level M4: Followers have high competence and high commitment and confidence.

In Hersey and Blanchard’s approach, the key to successful leadership is matching the proper leadership style to the corresponding maturity level of the employees. As a general rule, each of the four leadership styles is appropriate for the corresponding employee maturity level:

- Telling style works best for leading employees at the M1 level (low competence, low commitment).

- Selling style works best for leading employees at the M2 level (low competence, high commitment).

- Participating style works best for leading employees at the M3 level (high competence, low commitment/confidence).

- Delegating style works best for leading employees at the M4 level (high competence, high commitment/confidence).

Maturity levels and leadership styles

Identifying the employee maturity level becomes a very important part of the process, and the leader must have the willingness and ability to use any of the four leadership styles as needed.

Goleman’s Model of Situational Leadership

Another situational theory of leadership has been developed by Daniel Goleman. His theory incorporates his development of the concept of emotional intelligence. He develops that idea into six categories of situational leadership, describing the leadership style and suggesting when each style is most appropriate and likely to be successful:

| Pacesetting Leader | The leader sets aggressive goals and standards and drives employees to reach them. This works with highly motivated and competent employees, but can lead to burnout due to the high energy demands and stress levels. |

| Authoritative Leader | The leader authoritatively provides a direction and goals for the team, expecting the team to follow his lead. The details are often left up to the team members. This works well when clear direction is needed, but can be problematic if the team members are highly experienced and knowledgeable and might resent being dictated to. |

| Affiliative Leader | A positive reinforcement and morale-boosting style. The leader praises and encourages the employees, refraining from criticism or reprimand. The goal is to foster team bonding and connectedness, along with a sense of belonging. This approach works best in times of stress and trauma or when trust needs to be rebuilt. It is not likely to be sufficient as a long-term or exclusive strategy. |

| Coaching Leader | The leader focuses on helping individual employees build their skills and develop their talents. This approach works best when employees are receptive to guidance and willing to hear about their weaknesses and where they need to improve. |

| Democratic Leader | The leader intentionally involves followers in the decision-making process by seeking their opinion and allowing them a voice in the final decision. This works well when the leader is in need of guidance and/or the employees are highly qualified to contribute and there are not strenuous time constraints that require quick decisions. |

| Coercive Leader | The leader acts as the ultimate authority and demands immediate compliance with directions, even applying pressure as needed. This can be appropriate in times of crisis or disaster, but is not advisable in healthy situations. |

Normative Decision Theory

One final theory we will look at is Vroom and Yetton’s Normative Decision Theory. This approach is intended as a guide in determining the optimum amount of time and group input that should be committed to a decision. A leader has a number of options available to him in this regard:

- He can make a decision entirely by himself.

- He can use information from team members to make decisions.

- He can consult team members individually and ask their advice before making the decision.

- He can consult team members as a group before making the decision.

- He can consult the team as a group and allow the team as a whole to make the decision.

Victor Vroom and Phillip Yetton provide a model that helps leaders decide when to use each approach. The model walks leaders through a series of questions about the decision to be made, and the answers will lead the decision maker to the suggested approach. The questions focus on a few key factors:

- Is decision quality highly important?

- Does the leader have sufficient information to make the decision?

- Is it highly important for team members to accept the decision?

- Are the team members likely to accept the leader’s decision if he makes it individually? What if he makes it with their consultation?

- Do the team members’ goals match those of the leader and organization?

- Is the problem structured and easily analyzed?

- Do team members have high levels of expertise in the matter to be decided?

- Do team members have high levels of competence in working together as a group?

Leaders are challenged not only to make good decisions, but to decide who decides. At times, the best choice is to involve others in the decision.