10.4 Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and the Workplace of the Future

LEARNING OBJECTIVESBy the end of this section, you will be able to:

As we have seen earlier in this chapter, general advances in computer technology have already enabled significant changes in the workplace. In this module, we will look at how future workforce demographics may be affected by existing and emerging technologies. The combination of automation and robotics has already changed not only the workplace but everyday life as well. It also comes with a host of ethical and legal issues, not least being where humans will fit in the workplace of tomorrow. Managers of the future may ask, “Does my company or society benefit from having a human do a job rather than a robot, or is it all about efficiency and cost?” |

Robotics and Automation in the Workplace

Advances in the field of robotics—a combination of computer science, mechanical and electronics engineering, and science—have meant that machines or related forms of automation now do the work of humans in a wide variety of settings, such as medicine, where robots perform surgeries previously done by the surgeon’s hand. Robots have made it easier and cheaper for employers to get work done. The downside, however, is that some reasonably well-paying jobs that provided middle-class employment for humans have become the province of machines.

A McKinsey Global Institute study of eight hundred occupations in nearly fifty countries showed that more than 800 million jobs, or 20 percent of the global workforce, could be lost to robotics by the year 2030.74 The effects could be even more pronounced in wealthy industrialized nations, such as the United States and Germany, where researchers expect that up to one-third of the workforce will be affected. By 2030, the report estimates that 39 million to 73 million jobs may be eliminated in the United States. Given that the level of employment in the United States in mid-2018 is approaching 150 million workers, this potential loss of jobs represents roughly one-quarter to one-half of total current employment (but a smaller share of employment in 2030 because of future population and employment growth).

The big question, then, is what will happen to all these displaced workers. The McKinsey report estimates that about twenty million of them will be able to transfer easily to other industries for employment. But this still leaves between twenty million and more than fifty million displaced workers who will need new employment. Occupational retraining is likely to be a path taken by some, but older workers, as well as geographically immobile workers, are unlikely to opt for such training and may endure job loss for protracted periods.

In developing countries, the report predicts that the number of jobs requiring less education will shrink. Furthermore, robotics will have less impact in poorer countries because these nations’ workers are already paid so little that employers will save less on labor costs by automating. According to the report, for example, by the same date of 2030, India is expected to lose only about 9 percent of its jobs to emerging technology.

Which occupations will be most heavily affected? Not surprisingly, the McKinsey report concludes that machine operators, factory workers, and food workers will be hit hardest, because robots can do their jobs more precisely and efficiently. “It’s cheaper to buy a $35,000 robotic arm than it is to hire an employee who’s inefficiently making $15 an hour bagging French fries,” said a former McDonald’s CEO in another article about the consequences of robots in the labor market.75 He estimated that automation has already cut the number of people working in a McDonald’s by half since the 1960s and that this trend will continue. Other hard-hit jobs will include mortgage brokers, paralegals, accountants, some office staff, cashiers, toll booth operators, and car and truck drivers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that eighty thousand fast-food jobs will disappear by 2024. As growing numbers of retail stores like Walmart, CVS, and McDonald’s provide automated self-checkout options, it has been estimated that 7.5 million retail jobs are at risk over the course of the next decade. Furthermore, it has been estimated that as self-driving cars and trucks replace automobile and truck drivers, five million jobs will be lost in the early 2020s.

Jobs requiring human interaction are typically at low risk for being replaced by automation. These include nurses and most physicians, lawyers, teachers, and bartenders, as well as social workers (estimated by the BLS to grow by 19 percent by 2024), hairstylists and cosmetologists, youth sports coaches, and songwriters. McKinsey also anticipates that specialized lower-wage jobs like gardening, plumbing, and care work will be less affected by automation.

The challenge to the economy, then, will be how to address the prospect of substantial job loss; about twenty million to fifty million people will not be able to easily find new jobs. The McKinsey report notes that new technology, as in the past, will generate new types of jobs. But this is unlikely to help more than a small fraction of those confronting unemployment. So the United States will likely face some combination of rapidly rising unemployment, an urgent need to retrain twenty million or more workers, and recourse to policies whereby the government serves as an employer of last resort.

ETHICS ACROSS TIME AND CULTURESAdvances in Robotics in JapanJapan has long maintained its position as the world’s top exporter of robots, selling nearly 50 percent of the global market share in terms of both units and dollar value. At first, Japan’s robots were found mainly in factories making automobiles and electronic equipment, performing simple jobs such as assembling parts. Now Japan is poised to take the lead by putting robots in diverse areas including aeronautics, medicine, disaster mitigation, and search and rescue, performing jobs that human either cannot or, for safety reasons (such as defusing a bomb), should not do. Leading universities such as the University of Tokyo offer advanced programs to teach students not only how to create robots but also how to understand the way robot technology is transforming Japanese society. Universities, research institutions, corporations, and government entities are collaborating to implement the country’s next generation of advanced artificial intelligence robot technology, because Japan truly sees the rise of robotics as the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” New uses of robots include hazardous cleanup in the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami disaster that destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. After those events, Japan accelerated its development and application of disaster-response robots to go into radioactive areas and handle remediation. In the laboratory at the University of Tokyo School of Engineering, advances are also being made in technology that mimics the capabilities of the human eye. One application allows scientists a clear field of vision in extreme weather conditions that are otherwise difficult or impossible for humans to study. Japanese researchers are also developing a surgical robotic system with a three-dimensional endoscope to conduct high-risk surgery in remote mountainous regions with no specialized doctors. This system is in use in operating rooms in the United States as well, but Japan is taking it a step further by using it in teletherapy, where the patient is hundreds of miles away from the doctor actually performing the surgery. In Japan’s manufacturing culture, robots are viewed not as threats but as solutions to many of the nation’s most critical problems. Indeed, with Japan’s below-replacement fertility since the mid-1970s, Japan’s work force has been aging quite rapidly; in fact, beginning in the period from 2010 to 2015, the Japanese population started shrinking. Clearly, robots are potentially quite important as a means to offset prospective adverse consequences of a diminishing labor force. Critical Thinking

|

Artificial Intelligence

Although some robots are remotely controlled by a human operator or a computer program written by a human, robots can also learn to work without human intervention, and often faster, more efficiently, and more cheaply than humans can. The branch of science that uses computer algorithms to replicate human intelligent behavior by machines with minimal human intervention is called artificial intelligence (AI). Related professions in which the implementation of AI might have particular impact are banking, financial advising, and the sales of securities and managing of stock portfolios.

According to global consulting giant Accenture, AI is “a collection of advanced technologies that allows machines to sense, comprehend, act and learn.” Accenture contends that AI will be the next great advance in the workplace: “It is set to transform business in ways we have not seen since the Industrial Revolution; fundamentally reinventing how businesses run, compete and thrive. When implemented holistically, these technologies help improve productivity and lower costs, unlocking more creative jobs and creating new growth opportunities.”76 Accenture looked at twelve of the world’s most developed countries, which account for more than half of world economic output, to assess the impact of AI in sixteen specific industries. According to its report, AI has the potential to significantly increase corporate profitability, double rates of economic growth by 2035, increase labor productivity by as much as 40 percent, and boost gross value added by $14 trillion by 2035, based on an almost 40 percent increase in rates of return.77 Even news articles have begun to be written by robots.78

LINK TO LEARNINGRead this article about AI and its applications. Also, read this article about how some startups are creating new AI-related technology and products to automate accounting systems to learn more. |

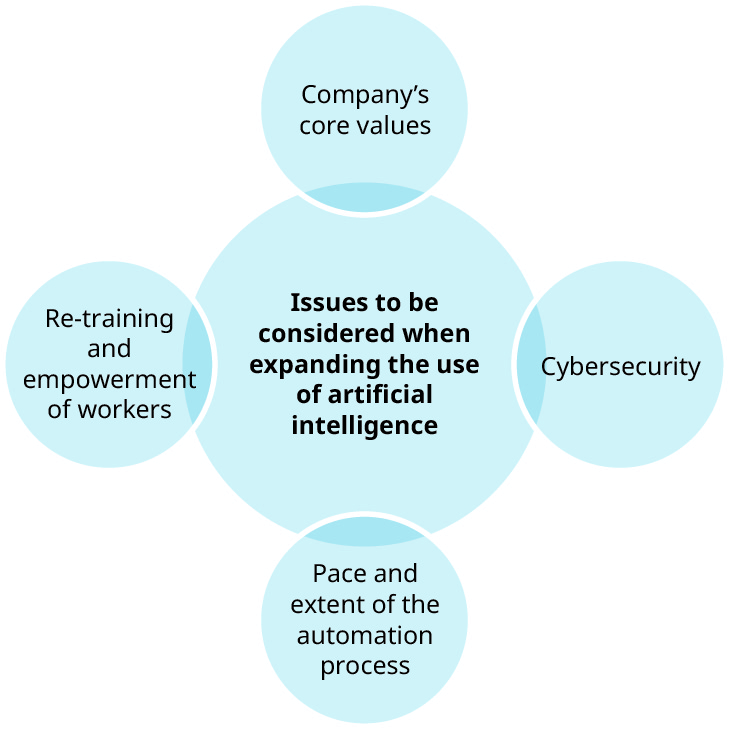

A report by KPMG, another global consulting and accounting firm, indicates that almost 50 percent of the activities people perform in the workplace today could be automated, most often by using AI and automation technology that already exist. The ethical question facing the business community, and all of us on a broader level, is about the type of society in which we all want to live and the role automation will play in it. The answer is not simply about efficiency; a company should consider many variables as it moves toward increased automation (Figure 10.9).

| Figure 10.9 Managers should balance multiple variables as the workplace moves toward increased use of artificial intelligence, automation, and robotics. (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license) |

For example, as AI programs become better able to interact with humans, especially online, should a company be required to inform its customers if and when they are dealing with any form of AI and not a person? If people cannot tell when they are communicating with an AI program and not a human being, has an AI-controlled computer or robot reached a form personhood? Why or why not? Although traditional business ethics can provide us with a starting place to answer such questions, we will also need a philosophical approach, because we also need to decide whether it is necessary to have consciousness to be considered a person. This issue is further muddied when a human employee largely is tapping AI i to serve customers or clients. Should this combination of human and AI assistance be made patently clear?

Another issue in AI and all forms of automation is liability. According to Reuters News, “lawmakers in Europe have agreed on the need for [European Union]-wide legislation that would regulate robots and their use, including an ethical framework for their development and deployment, as well as the establishment of liability for the actions of robots, including self-driving cars.”79 The legal and ethical questions in assigning liability for decisions made by robots and AI are not only fascinating to debate but also an important legal matter society must resolve. The answers will one day directly affect the day-to-day lives of billions of people.

Citation/Attribution

Attribution information

- If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a print format, then you must include on every physical page the following attribution:

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a digital format, then you must include on every digital page view the following attribution:

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

Citation information

- Use the information below to generate a citation. We recommend using a citation tool such as this one.

- Authors: Stephen M. Byars, Kurt Stanberry

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Business Ethics

- Publication date: Sep 24, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

© Dec 12, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

No Comments