Introduction to Digital Marketing

Overview

In this chapter, we discuss how digitalization is changing the ecosystem in which we conduct marketing activities. We start by defining marketing, value, and how value is created. We then go on to see how the media ecosystem and digital channels are transforming the logic we use to create value, moving away from representing the company to representing the customer. To set up the next chapter, we conclude by briefly discussing the consumer journey.

| Learning Objective |

| Understand that the main goal of marketing is to create value and how the changing ecosystem is transforming the ways we can achieve this goal. |

What Is Marketing?

According to the American Marketing Association — marketing’s top association — marketing is “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” (American Marketing Association 2013).

Our goal is to better understand how the consumer experience has been transformed and why it has become necessary to adopt a drastically different perspective on how to perform marketing online. Thus, as we reconceptualizere-conceptualize the ecosystem in which consumers and firms operate, we concentrate on the following elements of that definition: “processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value.”

In other words, the role of marketing is to create value for a broad range of stakeholders. In this textbook, we concentrate on value creation for consumers. We concentrate on value creation because consumers “do not buy products or services, they buy offerings which … create value” in their lives (Gummesson 1995, p. 250). Hence, our focus will be on understanding how firms can create value in consumers’ lives — and how they can do so online.

Firms create value for consumers in many different ways. If we rewind back a few decades, we find that our understanding of value creation was tainted by the work of economists, and value was mostly thought of as being based on products’ utility. Utilitarian value, therefore, denotes the value that a customer receives based on a task-related and rational consumption behavior (Babin et al. 1994). Since then, our understanding of value has vastly broadened to include other types of value, such as hedonic value — value based on the customer’s experience of fun and playfulness (Babin et al. 1994)—or linking value, which is based on the creation of interpersonal links between consumers (Cova 1997). This is important for digital marketers because it means that there are numerous avenues to contribute to consumers’ lives through value creation that expand beyond the use of a product by a consumer to achieve a specific task.

Another important transformation of our understanding of value creation over the last decade is the idea that value is always co-created (Vargo and Lusch 2004). Value is co-created through the meeting of consumers, with their own resources such as skills, expertise, and existing possessions, with that of firms and their resources, such as brand campaigns, service delivery models, and the products they sell.

Let’s see these notions concretized through an example: Before, we would have conceptualized a consumer as buying a car because they wanted to extract the utilitarian value associated with the product (i.e., moving from point A to point B). Value resided in the car and was transferred to a consumer when they put that product into use. Nowadays, we understand the purchase of a car as conceptually very different. First, consumers can buy a car for reasons other than going from point A to point B. Maybe they want to belong to a community of other consumers, or what is referred to as a consumption community, and buying this car allows them to do so. This community-oriented strategy is employed by iconic brands such as Harley-Davidson. Or maybe the consumers see the car as a recreational object, where the end is not important (i.e., where they are going), but how they get there is. This has led to many ads that emphasize the pleasure of driving, rather than more utilitarian characteristics such as fuel economy. And we now understand the value created by a car as emerging from the interaction of a consumer and the car. For example, creating value by consuming a sports car can be limited by the skills of the driver. The car has a set of characteristics from which consumers can create value, but they can only maximize value co-creation if they possess the expertise to do so. Similarly, a consumer can co-create value when buying a Harley-Davidson while riding it, but they might leave undeveloped value when they do not participate in the worldwide community of Harley-Davidson drivers.

To sum up, value exists in many different ways, and it is always the result of the interaction between a consumer and a firm (and its products and services). This has important implications for digital marketing, one of them being the creation of content. Many firms participate in creating value in consumers’ lives by offering free content. This content can have hedonic value, such as a humorous YouTube video. It can also help consumers better their skills and knowledge, such as online tutorials. By increasing consumers’ expertise, firms allow consumers to expand their resources, which can lead them to create more value when consuming products. We will come back to this idea in the conclusion of this chapter.

How do firms create value?

For the last 30 years, the dominant paradigm for understanding how firms create value for consumers has been market orientation. Market orientation refers to the “the organization-wide generation of market intelligence, dissemination of the intelligence across departments and organization-wide responsiveness to it” (Kohli and Jaworski 1990, p. 3). By this, we mean that organizations create value by generating information and disseminating this information throughout the firm in order to properly respond to it. This is done by generating and responding to information about customers, or what is referred to as customer orientation, and generating and responding to information about competitors, or what is referred to as competitor orientation. For this reason, marketing academics and practitioners typically aim to identify and respond to customer needs as well as examining and responding to their competitors’ efforts. Being market-oriented has been found to be necessary for a firm to compete in markets effectively (Kumar et al. 2011). For this reason, we will cover both customers and competitors in the first few chapters, and the strategic framework offered in this textbook is centered around answering customers’ needs, goals, and desires, ideally more effectively than the competition does.

Now that we have defined the bases of marketing, we turn our attention to change brought about by the internet and how it transformed the ways that firms create value for consumers.

Creating Value in the Digital Age

Canadian media scholar Marshall McLuhan famously wrote that “the medium is the message” (McLuhan 1964). By this, he meant to emphasize that the characteristics of a medium (e.g., TV vs. print vs. internet) played an important role in communications, in addition to the message. We conclude this chapter by showing how the internet, as a medium, has played a transformative role in shaping the message and what this means for marketing.

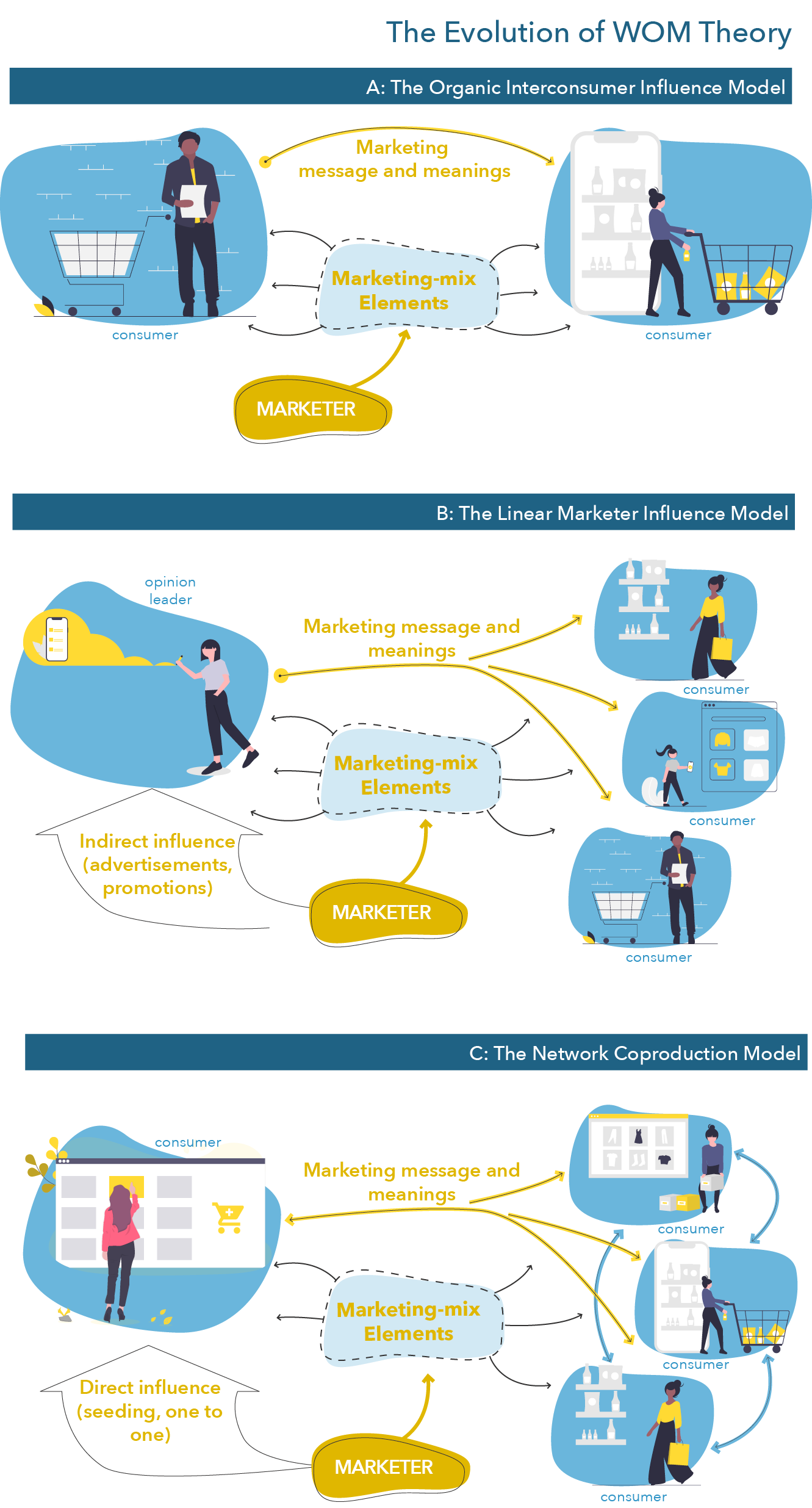

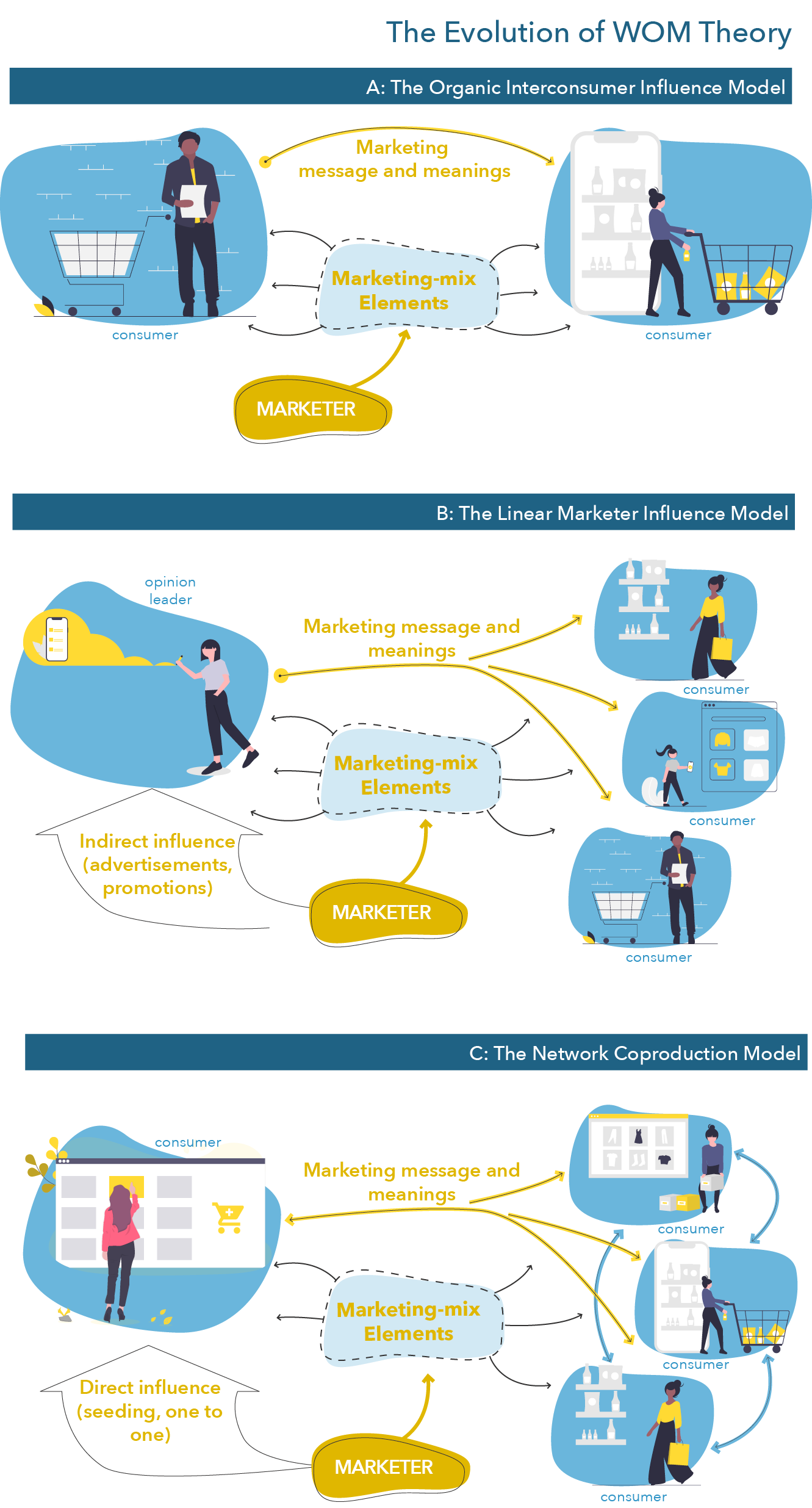

The ways messages are diffused to consumers have been vastly transformed since the 1950s. In reviewing word-of-mouth (WOM) models (Figure 1.1), Kozinets and co-authors (2010) identify three periods that are useful in conceptualizing how the diffusion of messages from firms to consumers has evolved.

Figure 1.1 The Evolution of WOM Theory

In the 1950s, the diffusion of messages echoed a view found in the very successful series Mad Men: advertising firms would create what they believed to be a message that could sell products and would use mass media such as TV, newspapers, magazines, and the radio to diffuse these messages. Word of mouth was organic, in the sense that it happened between consumers without interventions from firms. This is known as the organic interconsumer influence model.

In the 1970s, theories started to recognize that some individuals held more power than others to influence other consumers. Increasingly, these influential consumers and celebrities were leveraged by firms to diffuse their messages. This is known as the linear marketer influence model because in these earlier efforts, such influencers were believed to faithfully diffuse the message created by firms and their advertising agencies.

The emergence of the internet led to a third transformation in how we understand message diffusion and word of mouth and a movement toward a network co-production model. In this last model, consumers like you and me, online communities, and other types of networked forms of communication (such as publics created through hashtags, see Arvidsson and Caliandro 2015), have an increasing role to play not only in diffusing messages but also in transforming them.

Marketers have capitalized on this new mode of diffusion for messages by directly targeting influencers who are part of consumer networks and communities, which has resulted in the explosion of influencer marketing and the rising influence of micro-influencers. They have also developed capacities, such as social media monitoring, to identify emergent discourses on and around their brands, which sometimes completely reinterpret brand meanings.

The increased power of consumers in creating, modifying, and diffusing messages on and around brands has led, for example, to the creation of doppelgänger brand images, “a family of disparaging images and meanings about a brand that circulate throughout popular culture” (Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel 2006). Or, to simplify, consumers now create alternative campaigns that tarnish the intended image initially created by brands. Consumers using Twitter to diffuse alternative brand meanings or groups of consumers such as 4chan co-opting advertising campaigns are examples of this. For firms, the increased role of consumers in the creation and diffusion of messages has important implications for value creation: firms now have to consider not only how their messages can be amplified by consumers but also how they could be co-opted, reshaped, and resisted.

Another transformation brought about by the internet is media and audience fragmentation. In the 1970s, All in the Family was for a few years the top-watched TV show in the US. At its peak, it was watched by a fifth of the population. The 1980 finale of the hit series Dallas was watched by 90 million viewers, or more than 75% of the US television audience, while the last episode of M*A*S*H was watched by 105 million people. The last finale to make the top 10 list was Friends, in 2004, as the adoption of broadband internet accelerated.

Consumers have an increasing number of options for media-based entertainment. Traditional media companies are now competing against user-generated content found on social media websites such as Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok. Younger consumers have moved en masse to these new media, complicating the creation of advertising campaigns. Media fragmentation and the rise of internet in the lives of consumers has led to the emergence of the concept of the attention economy.

This is not a new concept. In 1971, Simon was already discussing how “information consumes … the attention of its recipients,” and Bill Gates was stating in 1996 that “content is king.” The implications for digital marketing had been recognized as early as the mid-1990s, when Mandel and Van der Leun mentioned in their book Rules of the Net how “attention is the hard currency of the cyberspace.” Goldhaber (1997) would add that “as the Net becomes an increasingly strong presence in the overall economy, the flow of attention will not only anticipate the flow of money but eventually replace it altogether.” This has led to a drastic rethinking of how to do marketing online and is intrinsically tied to the rise of inbound marketing and content marketing.

To recap, a few decades back, information was rather scarce; people, for the most part, consumed information from only a few sources, and companies could rather easily target consumers to diffuse their advertising messages. Nowadays, information is plentiful, consumers are diffused over a largely fragmented media ecosystem, and it has become more difficult for companies to diffuse their advertising messages to a mass of consumers, which can work against them. That difficulty, and the development of targeting technologies that have transformed how we can send messages to consumers, have led to two important transformations for marketers and how we understand value creation for consumers.

Finding Consumers vs. Being Found

The first transformation was a movement away from finding consumers toward being found by consumers.

What does this mean?

If we rewind history, it used to be that marketers would “find” consumers: They would use market research reports in order to understand where consumers hung out so as to place advertising there, what they watched so that they could run ads during their favorite shows, and understand their movements in a city so as to put ads and billboards in the right places. Although this still functions online—you can “find” consumers through online targeting by placing your ads on relevant websites—there has been an important switch toward consumers finding companies.

Consumers find companies through their normal everyday searches. In the chapter on consumers and their journey, we are going to see how finding companies expands the sets of brands that consumers consider before making a purchase.

How does this work?

Think of a need or a problem you might have. How do you usually go about answering this need or resolving this problem? Maybe you will ask a friend. Maybe you will go to a store and trust the salesperson. Or perhaps, as millions of consumers do every day, you will turn to the internet to do a search about your need or your problem. This is how thousands of consumers discover new brands and products every day! This has strong implications for digital marketers, one of the most important being content creation: In order to be found by consumers, you need to create content that addresses their problems. This is a topic we will explore in more detail when discussing content creation.

In short, it used to be that companies would find consumers and try to attract them to their stores or choose their brands through traditional media and advertising. Nowadays, our job has moved to creating content that informs, educates, and entertains consumers so that they can find us when they are searching for solutions to the needs they have or issues they are facing.

Representing the Company vs. Representing the Customer

The second transformation has been a move from representing yourself as a company to representing the customer.

What does this mean?

It used to be that, when finding consumers, companies would talk about themselves. Take, for example, this ad from Home Depot, which emphasizes how “Home Depot is more than a store … it is everything under the sun … all at a guaranteed low price” where you can save on flooring and where they have everything for your needs. In short, the ad is presenting the company and explaining why the company and its product are the best choice for the consumer. The ad represents the company.

Representing the customer means switching the focus to consumers’ needs and goals and the problems they are experiencing—and helping consumers address those problems. There are numerous ways to do so. Companies often create resources, such as tutorials and infographics, to help consumers solve their problems or achieve their goals. For example, Nike has developed an extensive set of videos to help consumers work out at home, train for running, or eat better (all of which can be found on their YouTube channel). This obviously represents opportunities for Nike to talk about their brand in every tutorial and connect with consumers, but the main goal is not to talk about how great Nike and its products are: It is to help consumers achieve their goals of training, running, and eating. It still serves the company well, though. When a consumer is searching for at-home exercises, they might come across Nike, consume their tutorials, and then, when it is time to purchase a new pair of sneakers or a tee to exercise in, be more likely to buy from Nike rather than a competitor.

Some brands have taken this a step further by offering tutorials tied with products they sell in-store, with a readily available shopping list for do-it-yourself projects. Home Depot, for example, offers tens of tutorials on their YouTube channel: This makes sense since the home improvement store sells products for such projects. By going a step further and representing the needs of the consumer, Home Depot can bring potential customers to their website when they want, for example, to build a fire pit. Within these tutorials, Home Depot presents a list of “Materials You Will Need,” which directly brings consumers to sections of their websites where they sell such products. The tutorial has thus become a great resource to create sales!

A Transformed Consumer Journey

What is a consumer journey? It is the experience of a consumer across the different stages of their buying process, which then extends to phases of relationships with a company. For example, let’s imagine you want a new pair of sneakers. You might have an existing pair. How satisfied were you with that pair? If you were highly satisfied and you still love the brand, you might go buy the same pair. This is partly why companies try to build loyal customers: to foster repeat sales. If you were unsatisfied, this model is not available anymore, or you want some variety, you might go and look for another pair of sneakers. You will then go through different stages: Having recognized a need you want to answer, you will move to discover options to answer that need, evaluate these options, make a choice and buy a new pair of sneakers, and then evaluate how much you like or dislike this pair.

As we will explore in the next chapter, these transformations and the new digital ecosystem in which consumers evolve have led to a drastically different way to enter in relationships with brands: Consumers now discover brands, rather than being discovered by them, and they start their relationships with those brands with online searches aligned with their needs, goals, and problems. The objective of companies doing marketing online is thus to be there when consumers need them. We will talk in the next chapter about how we can conceptualize such changes in transformations in the journey consumers take when buying products they want.