Chapter 6: Act: Creating Content

Overview

In this chapter, we cover some central activities associated with content creation. We introduce the chapter by explaining the importance of content creation and how content creation should resemble what your competitors are doing but also be different from them because of your own unique brand voice. We then turn our attention to structuring content creation activities. We examine how content creation can be guided by the RACE framework, the difference between gated and ungated content and when to use each kind, why and how to build topical relevance, and how pillar pages can help us do so. Finally, we conclude the chapter by discussing what a content creation calendar is and how it supports content creation efforts.

| Learning Objectives |

| Understand the basics of content creation, how it ties in with the RACE framework, gated and ungated content, pillar pages, and content creation calendars. |

The Importance of Creating Content

Content creation is important for two main reasons. First, it helps build a website’s relevance and authority, contributing to its ranking on search engines—according to most marketers, content marketing is the most efficient SEO tactic (Ascend2 2015, cited in marketingprofs.com). Websites with blogs also have four times more pages indexed on search engines, making them more likely to show up during searches (Forbes).

Content is also a cornerstone of customer acquisition strategies, and it is one of the most powerful tools for use in the RACE framework. According to HubSpot, a consumer consults three to five pieces of content during their journey toward making a purchase. Leads generated using inbound marketing efforts are also less costly by about half compared to leads generated using outbound efforts. Inbound leads are also 10 times more likely to convert (vs. outbound ones), and studies have shown that content marketing efforts boost company revenues by an average of 40% (HubSpot).

Creating Content

Before starting content creation efforts, a company should have in mind a clear persona and associated journey, understand its own website, and ideally understand how its competitors are positioning themselves on search engines (i.e., have performed a competitive keyword analysis).

Creating content is a balancing act. First, it is a balance in that you must be similar enough to competitors to address the general needs of the market and look like a trustworthy organization, while being different enough to attract customers. This idea of standing out while fitting in is termed “optimal distinctiveness.”

Second, it is a balance between what you can offer and what consumers want. When creating content, firms need to keep in mind that they should represent the customer. This entails understanding what customers are looking for based on their needs and challenges and how what they need evolves throughout their journey.

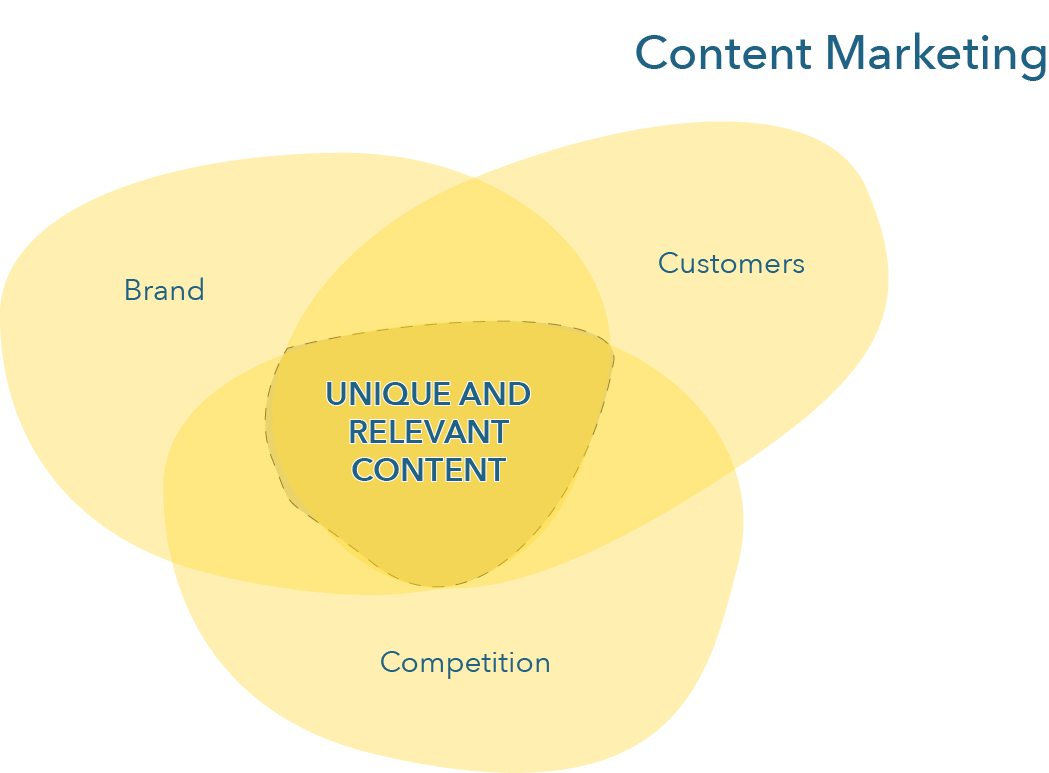

Creating unique and relevant content thus entails understanding the market and knowing the codes that organize content production, knowing what specifically about your brand gives it a unique voice (or “brand voice”), and combining these pieces of knowledge to create something unique that will interest consumers and is based on your capabilities, i.e., what you are able to do (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Content Marketing

Let’s explore this further through the example of creating content on Instagram.

Understanding the Competition and the Market

Something to keep in mind when creating content for social media platforms is associated with prototype and exemplar theories. Without getting into too much detail, the central idea here is that in order to stand out, you first must fit in.

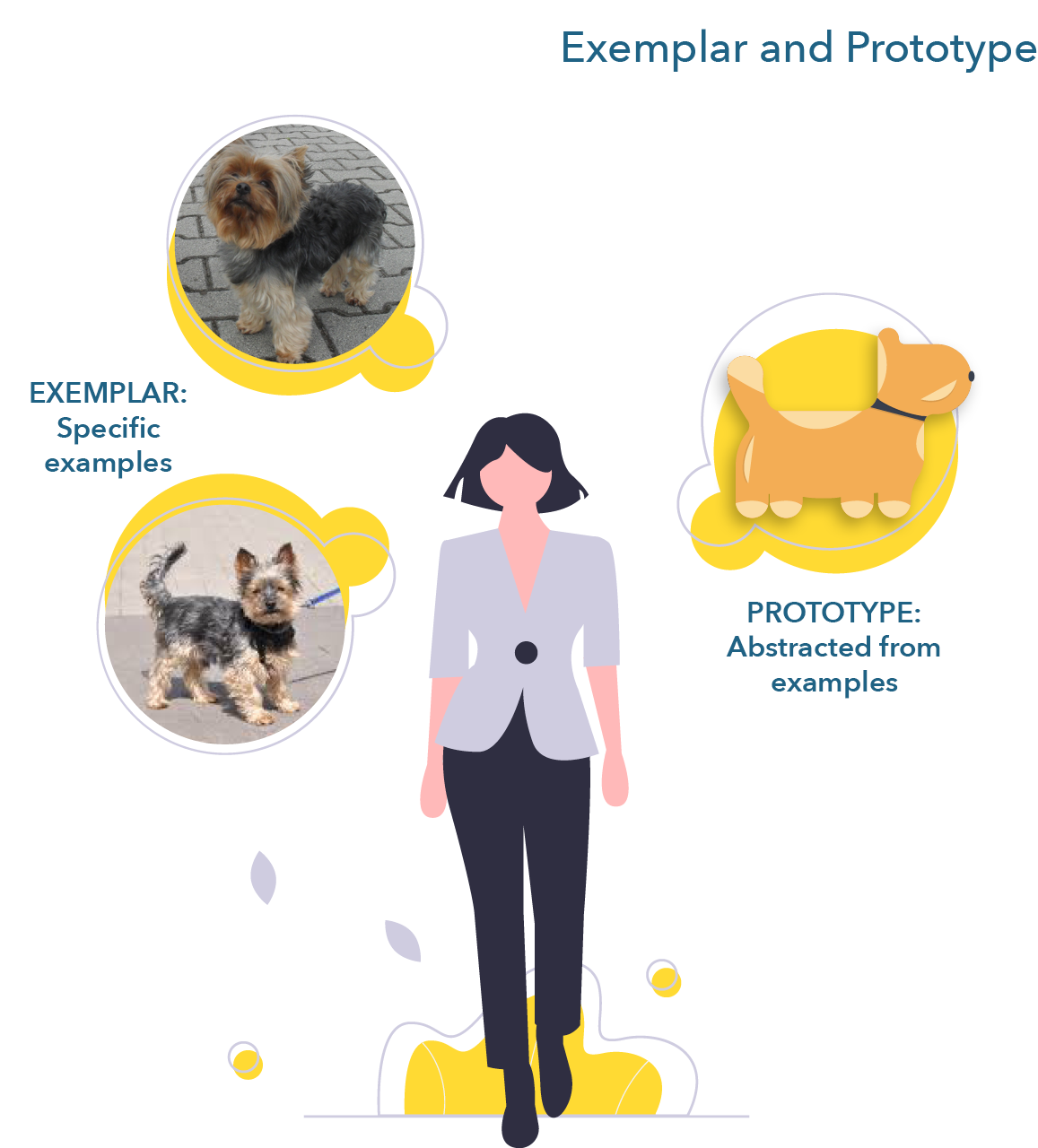

The idea goes as follows: Each category has some sort of a “standard” member, a “prototype” that people measure whatever is in this category against (or, from an exemplar perspective, each category has “dominant examples,” or exemplars, that are used to evaluate whatever is in this category; Figure 6.2). In order to fit in, such as to be considered legitimate as an Instagram account on cosmetics, cars, or tattoos, you must share attributes with the prototype or exemplar. This allows you to fit in.

Figure 6.2 Exemplar and Prototype

For example, fitness accounts tend to share characteristics in terms of what influencers look like (dressed in fitness attire and either looking fit or really, really fit), the setting in which they create their videos (typically, a gym), the kinds of things they post (how to exercise, diet posts, motivational posts, etc.), and so on.

Yet within the fitness category, there exist subcategories organized around different subtypes of fitness influencers. A first example is the fitness therapy profile, a type of fitness account exemplified by influencers such as achievefitnessboston, squatuniversity, and joetherapy. This type of account typically emphasizes science-based knowledge and instructional on how to properly practice fitness and recovery.

A strikingly different type of profile, still within the fitness category, is the “fitness motivational” account, exemplified in accounts such as zacaynsley, joesthetics, mssannamaria, and anna_delyla.

Knowing which subcategory a firm wants to participate in is important because not all personas will be reading all subcategories of fitness accounts. It also allows a better understanding of the category as a whole and how to potentially mix and match approaches, as exemplified by massy.arias.

Once you have gained membership by fitting in, your job is to find ways to distinguish yourself from others. In short, you want to fit in just enough that you are part of the category but you want to differentiate yourself enough that people will want to follow your Instagram account rather than one of your competitors. This is where the uniqueness of your brand comes into play.

Using Your Brand to Create Unique Content

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol, and/or other feature (e.g., Off-White and Off-White “quotes,” Coca-Cola and the Coke red, Bottega Venetta and its weave design) that identifies a company’s products or services and differentiates them from those of other companies.

Over the last three decades, practitioners and academics have developed many terms to help us better understand brands. For example, we now know what brands are more or less generally understood in the same way by consumers who have a certain image of the brands in their minds (brand image). The descriptive features that consumers use to describe these images are called brand attributes. We also know that marketers can play on this by assigning certain attributes—personality traits—to brands (brand personality). Marketers also strive to position their brand in a market in a way that is distinct and valued by consumers (brand positioning).

The main messages here are that brands serve to differentiate products and services, and, in our case, content created online, from other companies; that consumers form images of brands in their minds; and that, as digital marketers, we should strategically think of how to use brands to position ourselves, our products, our services and, importantly, our content.

Hence, once you have developed an understanding of the codes used around content creation in a market and how your competitors are uniquely positioned, the next step is to create content that will uniquely speak to consumers. Ideally, you will want this content to reflect who you are as a company, i.e., to reflect your brand.

Let’s take the example of brand personalities. Aaker (1997) identified five dimensions to the personality of brands:

sincerity(honest, genuine, cheerful)excitement(daring, spirited, imaginative)competence(reliable, responsible, dependable, efficient)sophistication(glamorous, pretentious, charming)ruggedness(tough, strong, outdoorsy, rugged)

We would expect that brands that aim to show a rugged image would create content differently from those aiming for a sophisticated one. Think, for example, of the latest Jeep ad that you might have watched and how it compares with the latest Mercedes ad that you have seen. Over time, interactions between consumers and touchpoints lead them to develop an image of your brand. Representing your brand in ways that align with the image you want to create in consumers’ minds is thus central.

Hence, to create unique content, ask yourself: What does my brand stand for? What do I want consumers to think of when they hear my brand name? How can my content properly showcase my brand?

Take Wendy’s, for example, which has become infamous for its sassy, cheeky, in-your-face, bordering-on-trolling social media presence. It, for example, challenged a teen to get a million retweets in exchange for a lifetime of chicken nuggets (the #nuggsforcarter campaign). It created a Spotify playlist taking shots at its competitors (as the company regularly does on Twitter). All of which, according to Wendy’s Chief Marketing Officer Kurt Kane, “is a natural extension of the Wendy’s brand Dave Thomas founded in 1969” (Fast Company).

Keeping Consumers in Mind

Last, and to reaffirm what has been said throughout the last chapters, your main role as a company when creating content is to represent the customer. That means to understand their needs and challenges, how what people look for varies throughout their journey, the types of searches they do (e.g., information, transaction, navigational; associated with ZMOTs; linked with their needs and challenges), and how you can answer consumers by providing them with content that is educational and entertaining.

Structuring Content Creation

In this second section, we are going to touch on a few key terms and approaches to help structure content creation: gated vs. ungated content and their respective roles in marketing campaigns, how to build topical relevance, and pillar pages.

Gated and Ungated Content

Gated content is “any type of content that viewers can only access after exchanging their information. Essentially, the content is hidden behind a form. Companies use gated content to generate leads and, ultimately, sales” (HubSpot). In contrast, ungated content is any content that users can freely access without having to exchange information.

An example of gated content is shown in Figure 6.3, where consumers are asked to “Download our exclusive trend reports.”

Figure 6.3 Gated Content Example

Gated content should be more extensive than ungated content, harder to find, and rather unique, so as to entice users to exchange their personal information for it. Examples include a white paper, an e-book, a report such as the one in Figure 6.3, a template, or a webinar—in other words, high value and rarer content.

You might ask why you should gate content, and the typical answer is to generate leads, such as in a lead generation landing page. Gated content should be thought of as the endpoint of a lead generation campaign, where consumers will provide their personal information, which will then allow a firm to enter into lead nurturing efforts, which we cover in the next chapter.

Typically, a firm will create ungated pieces of content (e.g., social media posts and blog posts) that will drive consumers to a piece of gated content. In other words, the content supporting the campaigns is ungated, and the endpoint where a visitor is converted into a lead is gated (see Figure 6.4, where a blog post is linked to an e-book).

Building Topical Relevance

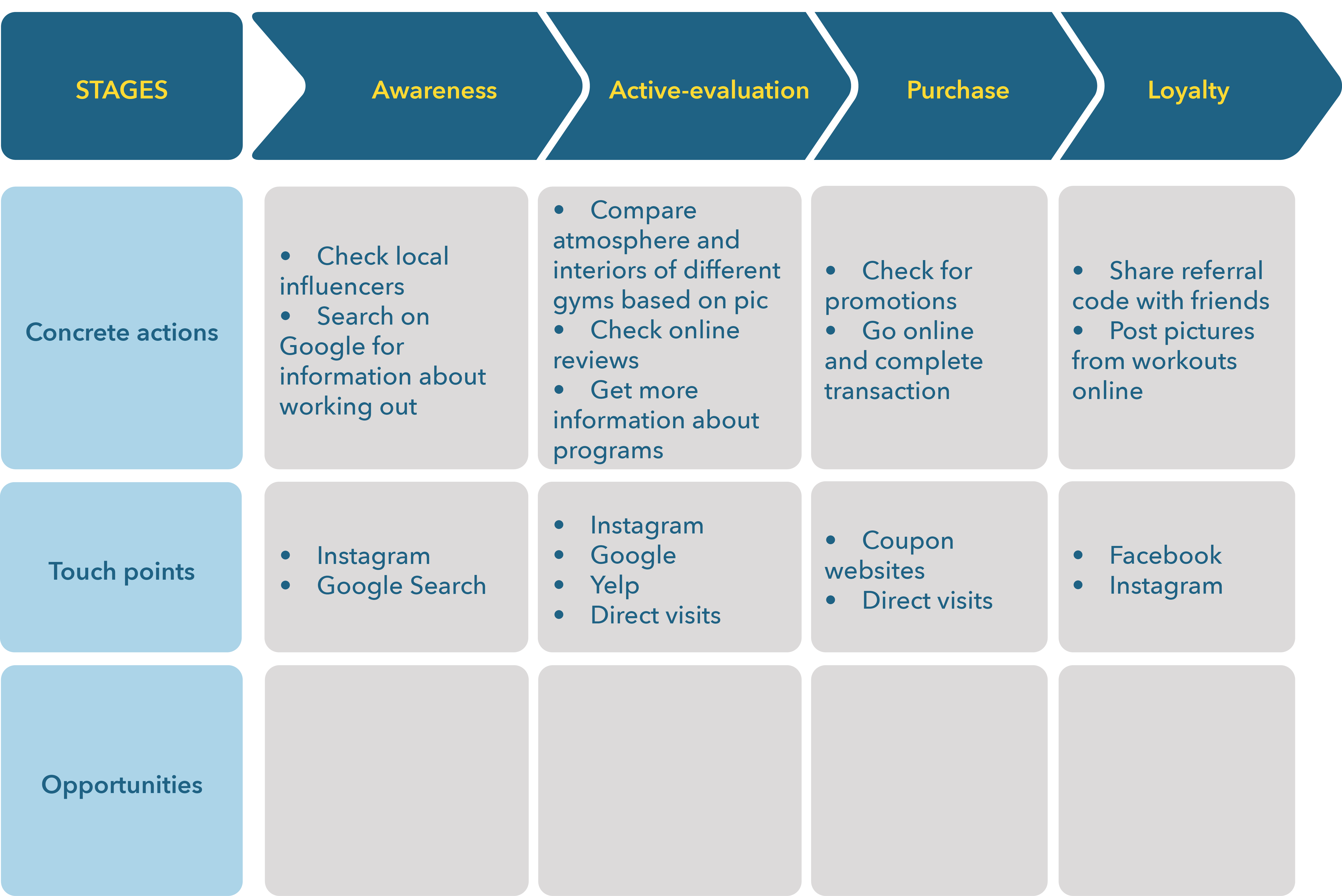

Over the last few chapters, we covered the basics of SEO, how to think about content creation and ads based on consumers’ needs and challenges, how to identify opportunities based on the concrete actions during their journey, and how to respond with ad hoc marketing activities.

Building topical relevance is part of a firm’s longer-term strategy for positioning itself and its web properties. It entails breaking down the general needs and challenges that consumers are experiencing into key topics that will orient our marketing efforts.

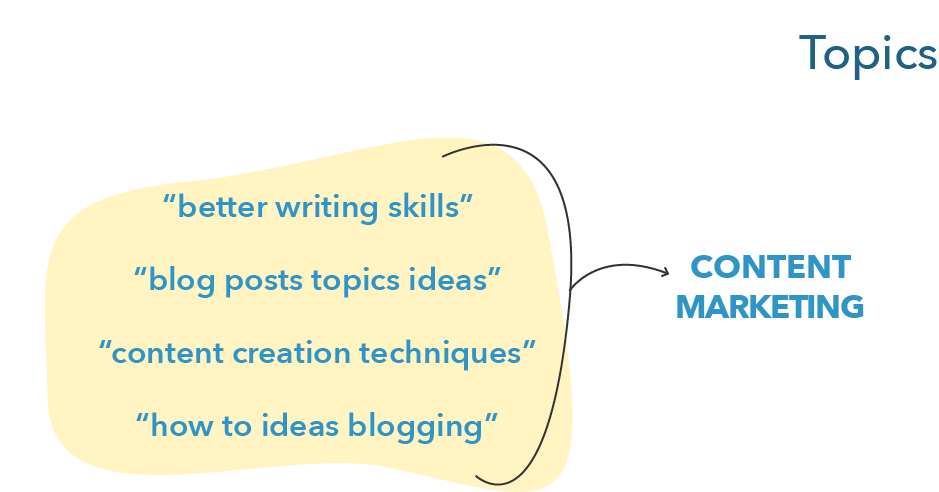

For example, if we wanted to build topical relevance on the topic of content marketing, we would come up with potential searches and areas of interest to create many blog posts, social media posts, and pieces of gated content on this topic (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5 Topics

To start building a web presence around certain key topics of interest to your consumers, the first step is to identify which topic you are interested in. A first, customer-driven, way to identify topics is by looking at the type of searches being carried out by consumers, which can be done using tools such as Google Trends or Search Reports in Google Analytics. Firms can also survey and interview consumers to better understand what is relevant to them, what their key needs and challenges are, and how they turn to the web to help address these. A second way to identify topics is through keyword analysis, as we discussed in Chapter 3.

Once a topic has been identified (e.g., content marketing), firms will plan their strategy to slowly build their relevance on that topic. Viewed from this perspective, each piece of content (e.g., a blog post) aims at addressing one targeted search. For example, a blog post positioned on the keywords “better writing skills” will answer a piece of the puzzle of content marketing: how to improve one’s writing skills. These might be hundreds of subtopics associated with a specific topic, opening further opportunities for content marketing efforts. A topic is thus a general domain that can tie together many specific searches (as exemplified in Figure 6.5).

Over time, building topical relevance will help a website, as a whole, show up higher on SERPs. This is because it helps address the main factors on which websites are ranked that we covered in Chapter 3: It facilitates the creation of cross-links, will help consumers spend more time on a website, boosts page views, and so on. Consumers might enter the website on the page on how to better their writing skills, for example, and once they are done reading their blog post, see and click on a recommended post on how to generate blog post ideas, increasing page views and time spent on site.

RACE and Content Marketing

As we have briefly covered, the RACE framework helps our content strategy by informing the type of content we should be creating for each stage of the framework.

Content marketing professionals typically talk about three types of content: top of the funnel (ToFu) content, middle of the funnel (MoFu) content, and bottom of the funnel (BoFu) content. The funnel represents the purchase funnel, or what we have referred to thus far as the consumer journey (awareness, active evaluation, purchase, and post-purchase).

We can easily map each stage of the funnel with RACE stages and stages of the consumer journey.

ToFu content activities target the awareness stage of the consumer journey and align with the Reach stage. At the awareness stage, consumers are experiencing and expressing symptoms of a need, problem, or challenge they are facing. The content aims at educating them. The need, problem, or challenge that consumers are experiencing can vary in abstractness. For example, they might have lower-back pain and are looking for a solution. Or they might need a pair of new running shoes. Content should thus address problems in ways that match what consumers are experiencing.

MoFu content activities target the active evaluation stage of the consumer journey and align with the Act stage. At the active evaluation stage, consumers are looking to evaluate solutions. Content should thus speak directly to the solutions that consumers can use to solve their needs, problems, or challenges. The goal of the content is to facilitate active evaluation and to serve as a bridge from education to your product or service. It is still important to represent the customer and to limit persuasion efforts, but to balance this with slowly warming consumers to what you have to offer.

BoFu content activities target the purchase stage and align with the Convert stage. At the convert stage, consumers are looking to buy a product. Content at this stage should help consumers evaluate your product or service to persuade them to buy what you are offering over the offer of competitors.

Searches consumers might make throughout the funnel could include the following (Figure 6.6):

ToFu (awareness/problem): “How to get dog hair out of my carpet?”MoFu (evaluation/solution): “Vacuum vs. sticky roll”; “Bissel Dog Eraser vs. Dyson Top Dog”BoFu (purchase/product): “Best price Bissel Dog Eraser”

Figure 6.6 Funnel

Examples of content from a firm (e.g., Bissell) to match these searches could be some of the following:

ToFu: “Everything you need to know about getting dog hair out of carpets and furniture”MoFu: “Why vacuums are superior to sticky rolls”BoFu: “Save on the Price of Bissell Dog Hair Eraser”

Top of the Funnel

At the top of the funnel, content should educate and entertain consumers based on the need, problem, or challenge they are facing. If people don’t know they need your product or understand what their problem is, it is crucial to educate them on it!

The types of content that typically help here (although this is not a comprehensive nor an exclusive list) include blog posts, webinars, pillar pages, and longer-form content such as comprehensive guides, videos, and infographics.

Middle of the Funnel

In the middle of the funnel, content should help consumers evaluate their options and facilitate that evaluation by educating and entertaining consumers on possible solutions. The firm’s objective at this stage is to start generating leads.

The types of content that typically help here (although this is not a comprehensive nor an exclusive list) include lists (e.g., “Top 10 solutions for lower-back pain”), case studies, how-tos, descriptions of multiple products (aimed at educating, not selling), quizzes to help consumers discover solutions, and other types of templates to help consumers identify solutions for their problems.

Bottom of the Funnel

At the bottom of the funnel, content should inform and persuade consumers about your product or service. The firm’s objective at this stage is to convert leads into customers.

The types of content that typically help here (although this is not a comprehensive nor an exclusive list) include testimonials and reviews, product offers, trials, coupons, samples, demos, free assessments or consultations, persuasive product descriptions, and sales-oriented webinars.

Beyond the Purchase Funnel

Content strategy should not stop at the purchase stage. Beyond the purchase funnel, firms should strive to create content that helps retain and engage customers. This could entail, for example, motivating social sharing, testimonials, and reviews, and encouraging loyalty through online customer events.

The types of content that typically help here (although this is not a comprehensive nor an exclusive list) include customer support and help documentation, contests, and giveaways based on product use, community forums, and strategies to encourage user-generated content. We will cover strategies for this stage in the last chapter of this textbook.

Pillar Pages

A pillar page is a comprehensive resource page that covers a core topic in depth and links to high-quality content created for the supporting subtopics.

It helps achieve the following two important digital marketing objectives:

building topical relevancesupporting content strategy RACE objectives such asattracting visitorsconverting visitors to leadsconverting leads to customers

Pillar pages come in all shapes and forms. The Content Marketing Institute, for example, differentiates between 10x content pillars, resource pillars, and service pillars. The following list presents a few examples of pillar pages on a wide variety of topics:

https://www.typeform.com/blog/guides/brand-awareness/http://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/athenahealth/population-healthier/598/https://zapier.com/learn/remote-work/http://kapush.org/cat-litter/https://slack.com/intl/en-ca/state-of-workhttps://stronglifts.com/squat/

What do these pages have in common?

Typically, they are very, very long. They tend to use multiple types of media (e.g., text, images, and videos). They are well integrated within their domain and have many cross-links. They answer many problems around a topic of interest for consumers. As a result, they help boost SEO efforts. Remember the main factors on which websites are ranked?

direct visitstime on sitepages per sessionbounce ratereferring domains, backlinks, follow-backlinks, and referring IPscontent lengthkeywords in body, density, in title, and metavideo on page

Pillar pages can help with all of these factors! By being long and answering many problems and needs associated with a single topic, they are more likely than “normal” pages to become references on these topics. This should allow the reduction of bounce rate, since consumers are almost certain to find what they are looking for! These pages are also more likely to increase time on site because they give so many resources for consumers to go through. By allowing many cross-links, they can favor many pages per session. They allow for writing extensive content with many keywords and multiple types of media.

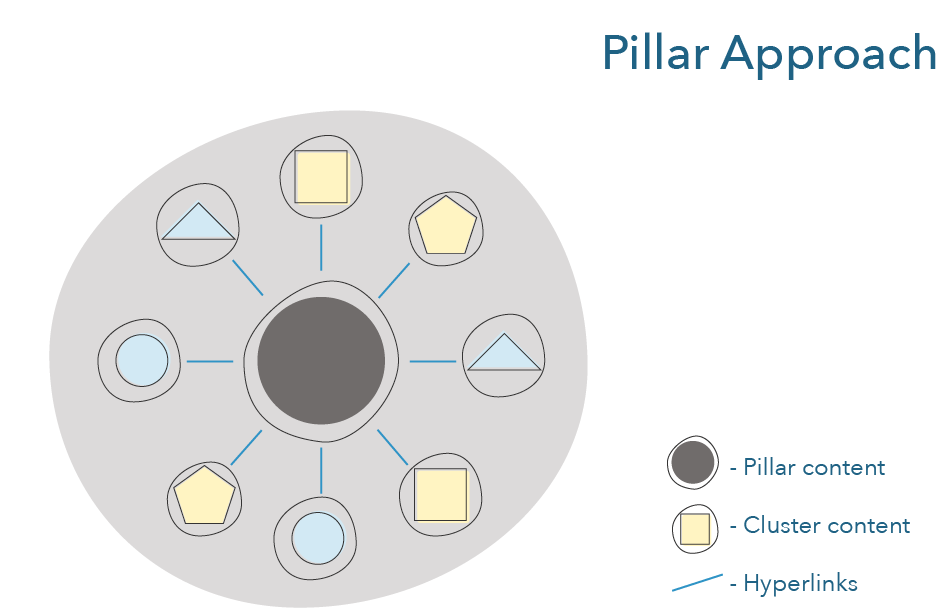

The main idea behind the creation of a pillar page is to identify a core topic of interest for consumers and break down this topic into topic clusters (or subtopics).

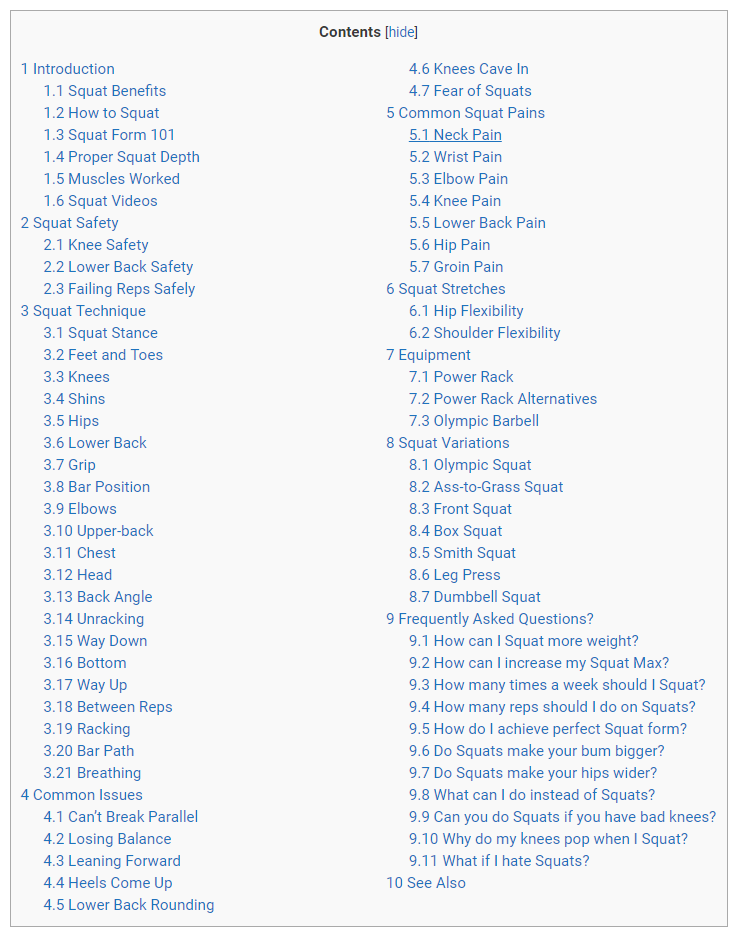

Take the Stronglifts squat pillar page, for example (Figure 6.7). The core topic of interest is “how to squat,” a question often asked by people interesting in exercising, bodybuilding, powerlifting, and the like.

When you enter this pillar page, you find a short summary on the squat and a few cross-links to guide consumers to other pages on the website, favoring higher page views. The summary is also useful because it can be used to hook people in, encouraging them to read on. The page then continues with several topic clusters organized around “how to squat”:

IntroductionSafetyTechniqueCommon issuesCommon squat painsStretchesEquipmentVariationsFAQs

Figure 6.7 Pillar Page Example

Each of these subtopics effectively represents subsections of the pillar page and addresses different needs, but they are all grouped into the same pillar page.

A pillar page can thus help build topical relevance because it provides a central and extensive resource on a major topic that can be well referenced (linked to) by other websites. It helps organize a website content around a core topic. If a pillar page is done well, the topic or problem it addresses should be one that a persona or multiple personas care about. Lastly, pillar pages help people easily navigate throughout multiple pieces of content on the same topic on the same webpage, providing a great user experience.

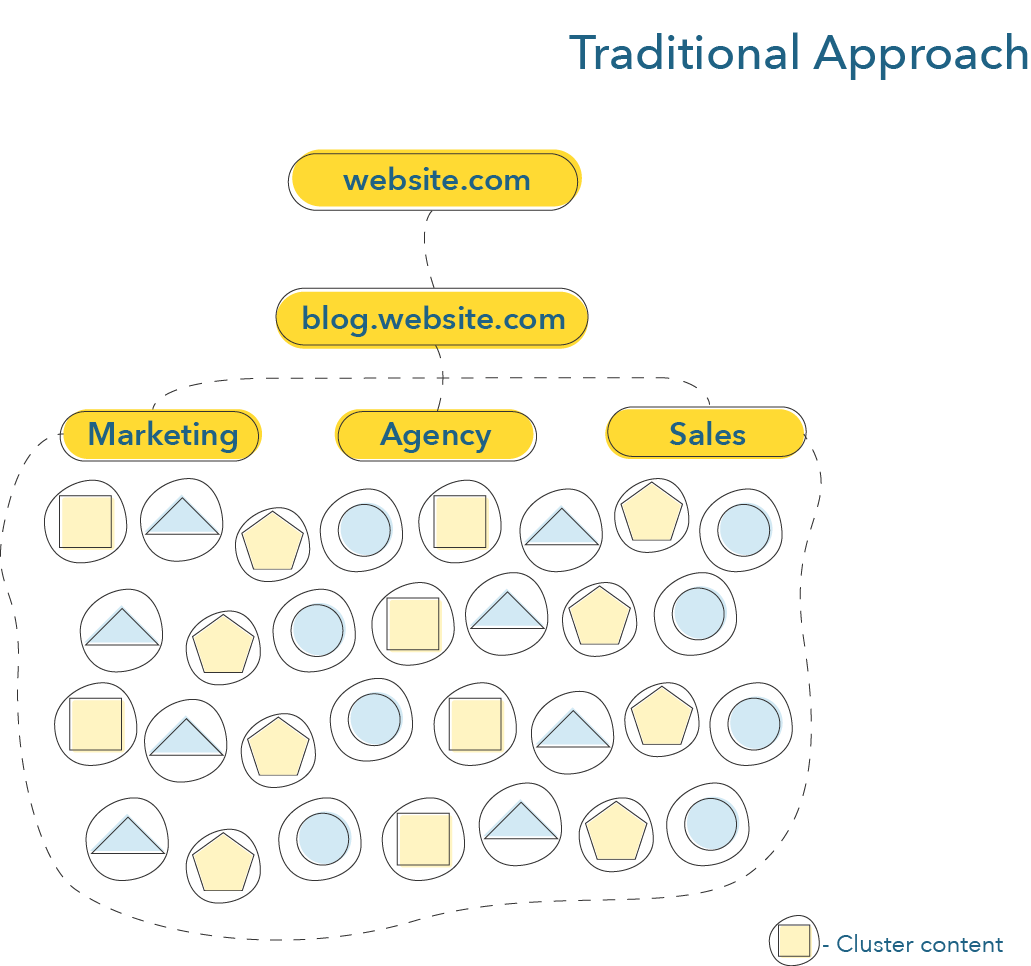

This is quite different from a typical content marketing approach that would have favored separate blog posts on all of these different subtopics and subsections of each subtopic!

Figure 6.8 illustrates the traditional content marketing approach and Figure 6.9 the pillar approach.

Figure 6.8 Traditional Approach

Pillar pages can also be used to support lead creation and sales.

A first way to do so is to use the pillar pages themselves. For example, a pillar page could include gated content, opt-ins (forms on the pillar page that ask for a consumer’s email address), and calls to action. Pillar pages that follow such an approach include the following examples:

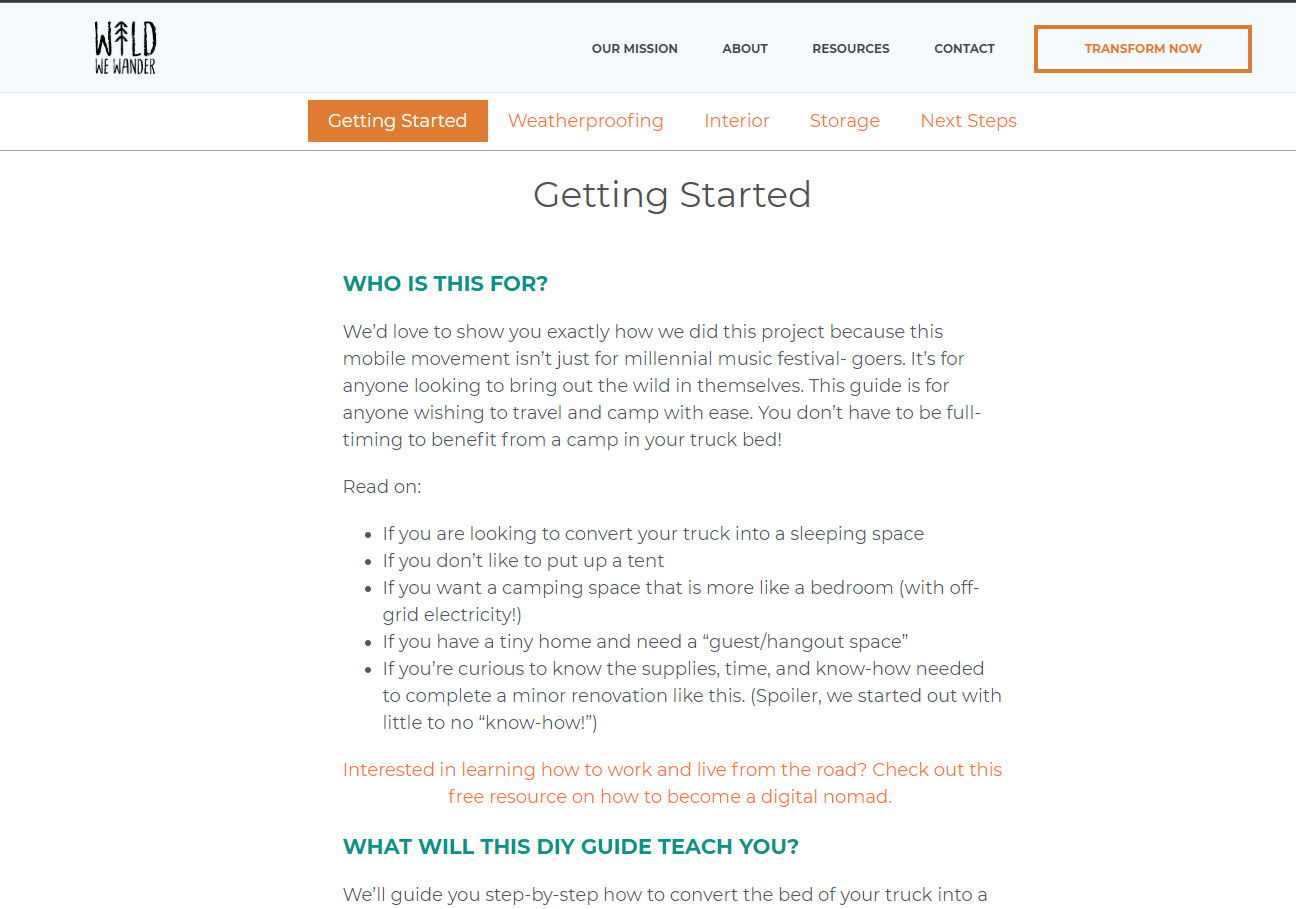

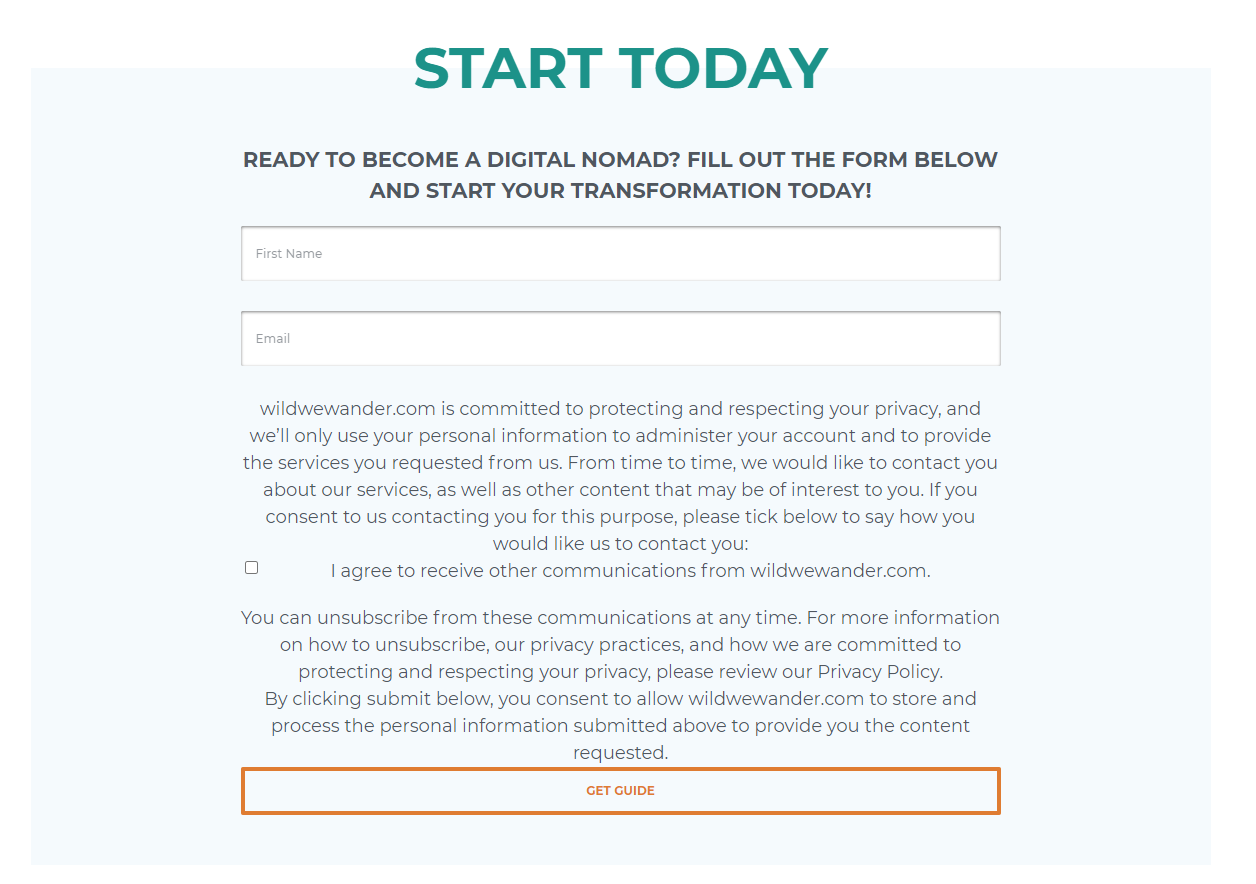

https://www.wildwewander.com/diy-truck-camperhttps://www.etuma.com/cx-professionals-guide-to-text-analysishttps://info.townsendsecurity.com/sql-server-encryption-key-management-definitive-guide

Take Wild We Wander, for example, and its pillar page on “how to DIY a truck camper.” This page (Figure 6.10) has all of the characteristics of a pillar page, but it also redirects consumers to a content asset (a free resource to become a digital nomad) that is a piece of gated content (Figure 6.11).

Figure 6.10 Pillar Page and Gated Content

Second, pillar pages can also be thought of as part of a longer-term strategy that includes other pieces of content. It often happens that companies will initially gate a pillar page and use it to generate leads. For example, the two pillar pages we presented so far could have been initially offered as e-books that offered all the information regarding “how to squat” and “how to DIY a truck camper.” The firms could have used these two gated content assets as part of a greater content marketing strategy, breaking down the e-book into smaller, more digestible pieces. Example of this could include short blog posts (“3 tips for a better squat,” “3 reasons why squats hurt your knees”), short videos (“the right squat position”), short social media posts (e.g., statistics and quotes from the e-book), and the like. Then, once the lead generation campaign was over, the e-book could have been turned into an ungated pillar page. Visually, this strategy can be represented as shown in Figure 6.12, where all of these “smaller” pieces of content link back to the gated e-book to generate leads.

Figure 6.12 Pillar Strategy

In fact, this is exactly the strategy that Unbounce used with their Conversion Centered Design e-book. Originally an e-book, the firm used it as a piece of gated content with supporting pieces of ungated content, including

a blog post highlighting the main lines,a SlideShare deck explaining the main principles, anda guest blog post on HubSpot.

These ungated pieces of content drove consumers to the e-book. To generate further leads, they also supported the launch of the e-book through other pieces of gated content, including

a webinar about Conversion Centered Design that captured leads for registration (gated) anda landing page to watch the webinar recording after the event.

Then, Unbounce took their e-book and transformed it into a pillar page (https://unbounce.com/conversion-centered-design/) and broke down the webinar, making it accessible on YouTube in six different videos.

Hence, if a firm plans to create pillar pages, it might be useful to think of how the page can first be embedded in a lead generation strategy before being made accessible more freely as a piece of ungated content.

Here are a few tips for forming such a strategy:

Find the core problems of your persona.Group these problems into core topics.Build each topic with subtopics.Identify content ideas for subtopics.Write an extensive piece of content.Fragment this piece of content into multiple pieces with different formats and different parts that can be used to bring people to the gate or foster interactions.Extend the reach of these parts on owned media and using paid activities.

Content Calendar

We conclude this chapter by discussing content calendars. Although pillar pages are a great long-term investment for web referencing and lead creation, most day-to-day content activities, be they posts on Facebook and Instagram or blog posts, are ad hoc activities. However, they should still be thought of from a mid-term perspective and integrated into a strategic approach to content marketing. This strategy should think of ways to build topic relevance over time, address many personas and stages in the journey process, and address all objectives of the RACE framework.

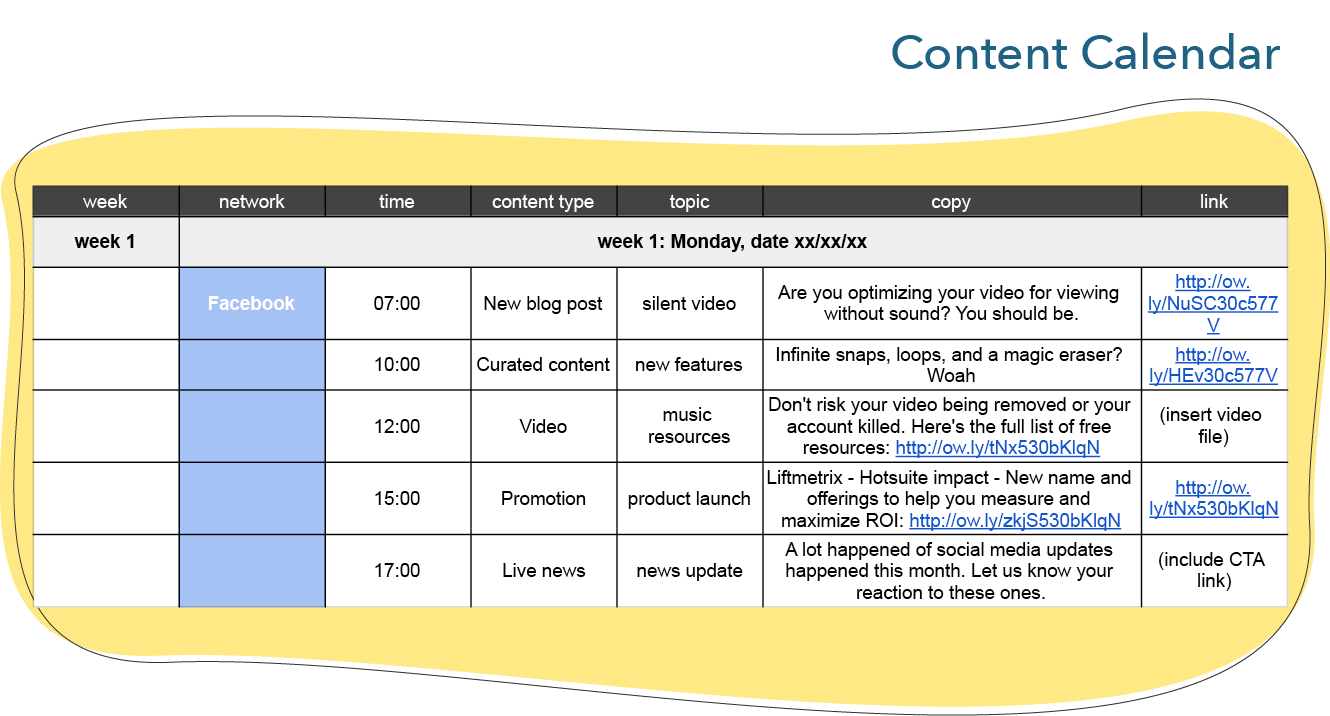

A great way to develop this strategy is through a content calendar. A content calendar maps future content creation activities. It answers questions like these:

Who is this content for (personas)?Which stage of the journey does this content address?What topic is it on?What keywords does it cover?

It can also help operationalize content marketing by providing information including the following:

date when it is supposed to go onlineauthor responsible for creating the content assetcontent typechannelheadlinecopycall to action

Figure 6.13 shows an example of a content calendar (text description here).

Figure 6.13 Content Calendar

Creating a content calendar should be done with reflexive intent. A firm should make sure that they are creating content for all stages of the journey, all personas, and all objectives of the RACE framework. By planning a month or two in advance and clearly mapping the personas, topic, journey stage, and RACE objectives that each piece of content addresses, a firm makes sure to create distributed efforts that do not privilege certain personas, stages, or objectives over others!

|

|