Institutions and Political-Economy Systems

Why Should I Care?

Would you prefer to live in a system where people are free to produce and buy what they want? Or would you prefer to live in an economy where most decisions are made by political committees? Sounds like a rhetorical question, but its not. These two political systems dominate our lives. For better or for worse. Free markets bring inequalities and environment issues, but command-style economies can become stultified and backward. Health institutions are the key to good feedback, no matter the political system.

This Lecture Has 3 Parts

- Institutions

- Command vs. Market

- Mixed Economy

Interview with Jean Francois Parent - on the Rule of Law

What is an Economic System?

Every economy uses resources to make goods and services. But the economic “environment” can influence the way the economy works. As you remember, a system is made of many components, two of which are discussed here: the controller, and the environment. These components of Control and Environment are a function of the social institutions at play in society.

-

Institutions

An institution is a structure of social order governing the behaviour of individuals. Even in free societies, there are many of these institutions. Think of the family, the Church, or sports organizations such as junior hockey. The study of institutions spans many disciplines, such as sociology, political science, anthropology, and economics. Within economics, the sub-branch of Political Economy, and Institutional Economics is specialized in dealing with the role of institutions in the economy.

In Canada, the major economic institutions are the justice system, the Parliament and its government, the education network and culture. These institutions go beyond the individual and live on after their members pass. They instill social order and govern behaviour. In such, they affect the economy.

Institution

A structure of social order governing the behaviour of individuals.

Political Economy

A social science that studies production, trade, and their relationship with the law and the government. A branch of both Political Science and Economics.

Institutional Economics

A sub-branch of economics which focuses on the role of institutions in shaping economic output.

Justice

Establishes and administers Rule of Law. Protects private property. Guarantees equality of humans towards law. Promotes competition through the respect of contracts. Police reduces crime and destruction of property (economic assets).

Government

Raises income and consumption taxes. Produces Defence, Health and Education services. Subsidizes certain industries. Acts as Referee in market disputes. Will oversee energy supply. Will draft labour, pollution, and competition laws. Dispenses aid to needy.

Education and Science

Provides training and knowledge to people. Increases labour productivity. Provides knowledge and new technology to industry.

Culture

A determinant of identity, moral values and beliefs, and artistic expression. Drives consumer tastes and preferences. Ex: in Quebec, culture affects the food market. Gourmet cheeses and French wines are sold in larger quantities here.

-

Command vs. Market

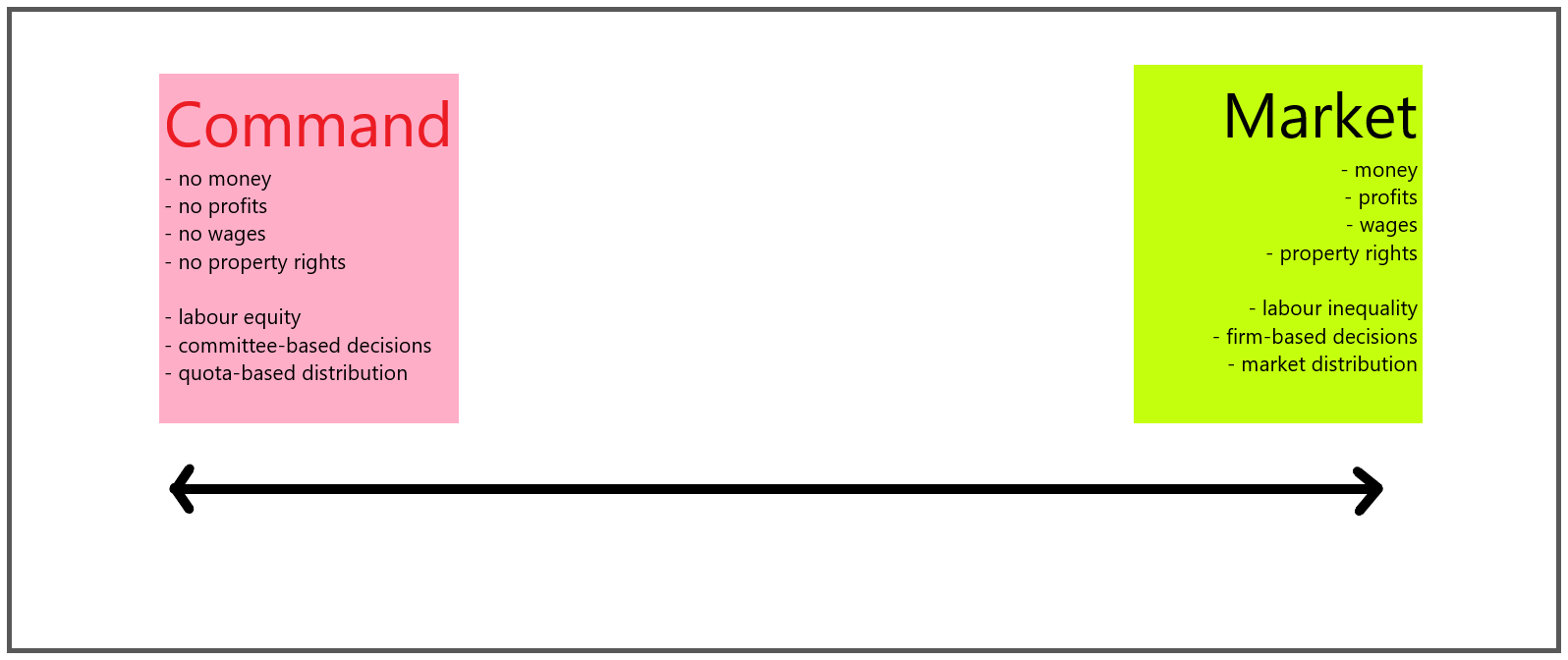

Institutions can steer the economy on a spectrum that separates two opposite political systems: Command economies, and Market economies.

The main institutional differences lie with the legal system and the monetary regime.

First, a regime of Rule of Law recognizes and upholds freely agreed contracts and transactions. This encourages entrepreneurship and free markets. If a State decides not to provide the legal framework necessary for markets, these usually won’t exist. For example, if there are no courts in a country to recognize a land deed, there is no private property, and no market for real estate. In this case, the person living on the land cannot sell it because there is no legal proof of ownership. Don't forget, markets are a creation of the state and its institutions.

Second, a pure command system has no money, whereas money is a hallmark of market economies. The decisions to produce inputs and outputs are handed down as 'commands', or orders. This is the case in most military operations, and purely socialist economies. When people need to obtain goods and services, these are provided through the use of tickets, or some form of permission. For example, communist regimes such as the USSR and Cuba had no private property for personal housing, which was provided by the State. There was no rent to be paid either. Families were assigned dwellings as they became available by State provision. In socialist regimes, food is distributed in stores, with coupons, or tickets, but no money.

Main differences between market economies and command economies

| Command |

Market |

|

| Domestic Currency |

No |

Yes |

| Foreign reserves |

Yes |

Yes |

| Coordination of production |

Committee |

Free Enterprise |

| Profits |

No |

Yes |

| Private property |

No |

Yes |

| Stock markets |

No |

Yes |

The actual situation of socialism within our economies is more complex than this table. There are many grey areas. To differentiate them, we will ask two questions to categorize economic systems.

First, who owns the resources? It may be the State, by force. Or, individuals may be permitted to own land, capital and labour. This makes a big difference.

Second, how are products distributed to consumers? This question refers to the allocation mechanism of the economy. The State can take care of this, with a system of vouchers, coupons and quotas. Or there may be a free market where suppliers sell their products to buyers in exchange of money or barter.

In a free-market economy, individuals are allowed and encouraged to own resources such as capital, and entrepreneurship. Markets are then where products meet consumers. State intervention is at a minimum: providing the basic services of policing, justice, Rule of Law and contract arbitration. Private property and the lure of profits regulate production decisions through free markets.

In a command economy, there is no money. Individuals cannot own resources. Production decisions are held by the State, which usually sets “plans” such as the famous soviet 5-year plans. The State also decides who gets products by controlling allocation: vouchers, coupons, etc. State intervention is at a maximum, profits are outlawed, there are no free markets, no private property, no contracts, and usually very little democratic Rule of Law.

Ownership-allocation grid of political-economy systems

|

|

Who owns resources? |

|

|

Who allocates products? |

Individual |

State |

|

Market |

A – Pure Capitalism |

C – Market Socialism |

|

State |

B – State Capitalism |

D – Pure Socialism |

A: Pure Capitalism

Individuals own resources and the market allocates products. This is Capitalism. There are no cases of countries with pure capitalism in every sector of the economy. Also known as Free market or Laisser-faire capitalism.

B: State Capitalism

individuals own resources, and the State allocates production. This is State Capitalism: see USSR, Quebec Egg Farms

Why Political-Economy?

In this text we refer to institutional regimes as political-economy systems, such as socialism and laisser-faire capitalism. Most textbooks would refer to them as 'economic systems'.

First, these regimes can be confused for political ideologies, which we will leave to political scientists and historians. In economics, these concepts are analyzed in their material aspect.

Second, since we have introduced Systems Analysis in this manual, we preferred to be specific when we discuss the political and institutional aspects of economic systems. Economic systems can be used to mean any system of production, whereas 'political-economy' systems is specific to the institutional makeup and the governance regime behind the economy.

In terms of systems analysis, political economy deals mostly with the components of feedback, environment and control.

-

The Canadian Mixed Economy

Canada is said to be a mixed economy. In many industries, free markets and entrepreneurs make the many economic decisions about what to produce and for whom. However, many industries in Canada have more in common with modern-day China than with a free-market utopia.

Electricity in Quebec is supplied by a State-owned monopoly: Hydro-Québec. This is MARKET SOCIALISM. The same is true of lotteries (Loto-Québec), of alcohol distribution (Société des alcools du Québec, SAQ), and of automobile insurance (Société d’assurance automobile du Québec, SAAQ).

Other wide swaths of economic activity are totally withdrawn of capitalism. Health services in Canada are provided by State-owned hospitals who do not sell their services on a free-market. That would be illegal. These health services are allocated through production quotas and paid for with mandatory income tax. In economic terms, this is truly socialist. The same is – partly – true of education. On one hand, public schools in Canada are owned by provincial governments and funded with income and municipal taxes. Schooling is not sold on markets. On the other hand, private schools may be owned by individuals and may sell their services freely. The education “industry” thus operates as a mixed economic system.

Green Policy

The question of institutions, and the degree to which you see a free-market economy in a country, can lead to very significant outcomes in terms of environmental policy. We certainly don’t have the space and time to explain every aspect of this topic. However, we can discuss a few examples.

We know that corporations can do a lot of environmental damage, even if they don’t do it on purpose. But if they can secure a revenue for their pollution (secondary production), they usually are very good at reducing their pollution, by capturing that output, and selling it on a market. Some smart research, funded by the State, can help corporations improve both the environment and their profits.

We also know that corporations can over exploit natural resources, such as over-harvest forests. However, if they are the owners of finite plots of land, they tend to manage the forests in more durable ways. Another point is that profit-seeking corporations may not be the best form of organization for logging trees. Maybe, this should be done by non-profit cooperative organizations who are run by locals, instead of investors.

Let’s not be blind to what is going on. Pollution happens every day. Large corporations are behind much of it. The solutions, however, usually lie in the types of institutions that are in place, and the types of rules that they enforce.

Climate Change Solution

We are coming to a point where people realize that our institutions need to work together to tackle the Climate Change issue.

Market-based solutions are possible. This is the idea behind the carbon tax, which has become the go-to solution for most economists. The idea is simple: tax the price of any input, and/or output, that uses carbon, such as oil, gasoline, and plastics. Users, whether industry or consumers, will opt for cheaper – and cleaner – alternatives.

We could also ban carbon products outright. But in the end, we have to work globally because one ton of carbon emitted in the atmosphere will affect all of the peoples of the earth, without discrimination. It doesn’t matter if for example, Norway reduces their emissions, if at the same time other countries are increasing their emissions.

Democracy Booster

It is necessary to consider institutional reform. In many countries, the rules of the game are allowing some states to increase their GHG emissions with no retribution.

For example, in Canada, there is not much New Brunswick, or Quebec, can do, to stop Alberta from exploiting its oil patch. Similarly, there is not much one country can do to impose GHG reductions on another country. Think of municipalities, provinces, states and federations. The design behind these orders of government may need to be re-considered.

Wrap-Up

Institutions organize the economy around the values and objectives of its society. Social institutions such as the family, religion, and sport are part of the cultural makeup of the economy. Government institutions such as courts, schools, and other government service providers, also shape the economy.

An Economic System is a set of rules that define who owns the resources, and who gets the products of the economy. Individual freedoms to own resources and trade define capitalism. State intervention defines socialism. Canada is in between.

Cheat Sheet

Rule of Law:

a society where a secular state uses a justice system of courts and legal defence, to enforce rules fairly over people. Everyone is treated equally by the law.

Private Property Rights:

Rights set by a justice system that guarantees the possibility for individuals to own property such as land, but also written work, music, and other creations of the mind.

Economic System:

a set of rules that define what to produce, how, and who gets the goods and services.

Capitalism:

individuals own resources and markets allocate products.

References and Further Reading

Colander, D. C., Rockerbie, D. W., & Richter, C. (2006). Macroeconomics, Third Canadian Edition. McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Friedman, M. (1990). Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. Harvest Books.

Jacobs, J. (1994). Systems of Survival, a Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics. New York: Random House.

Komlos, J. (2023). Foundations of real-world economics: What every economics student needs to know (Third edition). Routledge. Chapter 8 - The Case for Oversight, Regulation, and Management of Markets.

Marx, K. (1867) Das Kapital.

The world urgently needs to expand its use of carbon prices. (May 23, 2020). The Economist Newspaper.

A few cinematic suggestions

The following suggestions are for entertainment purposes. Many of the following films are subject to criticism from historians for inaccuracies or choosing to depict one side in a favourable light.

Tetris is a recent movie that covers the efforts of a US venture capitalist to secure the international rights to the game invented by Russian Alekseï Pajitnov in 1984 USSR. All property in the USSR was controled by the State, which agrees eventually to sell the foreign rights to the Japanese video game company Nintendo and later to The Tetris Co., co-owned by Pajitnov, and Dutch-American entrepreneur Henk Rogers.

Moscow on the Hudson is a 1984 film starring Robin Williams, who plays a Russian musician on tour to the US. He defects in New York City and falls in love with an Italian immigrant. The movie starts in Moscow where daily life is depicted with tongue-in-cheek moments, such as when Williams waits in a line-up for chicken, when in fact the store only has shoes. He decides to take a pair too large for himself, but which he can use as a bargaining chip with his superior.

Trotsky is an 8-episode series on the history of the Russian Bolchevik revolution, as seen from the point of view of Leon Trotsky, the leader of the revolution. The series debuted on Channel One in Russia in 2017 for the 100 year anniversary of the 1917 revolution. Trotsky's name had been taboo by Stalin and subsequent soviet period.

No Comments