Marshall's Supply and Demand

Why Should I Care?

How can you make predictions about the future? Markets are subject to complex environments, with a multiplicity of actors, and even more shocks coming in from all sorts of random directions. There is a way to sort through the chaos.

This Lecture Has 4 Parts

- Assumptions about price arbitrage

- Assumptions about buyers and sellers

- Types of industrial structure

- Dealing with outside forces

What is Marshall’s Supply and Demand?

British economist Alfred Marshall wrote the book on markets in the early 20th century. His work has become the foundation for micro-economics to this day. The supply and demand model aims to capture a whole industry, rather than individual transactions.

Photo credit: https://snl.no/Alfred_Marshall

The model Marshall put together imposes a single price on all of the buyers, and all of the sellers. To make this model work, there are a few assumptions that need to be made about the actors involved. An interesting aspect of the model is that if you change some of the assumptions, especially about sellers, you change the type of industry structure. In the case where a seller has extreme power over the market, we call this a monopoly and Marshall’s model allows us to predict what will most likely happen to prices and quantities offered in that situation.

In regards to systems analysis, supply and demand modelling has to do with two components of the economic system: control (buyers and sellers decide what they want to do), and feedback (information from prices influence buyers and producers). The model also allows to include the external environment, and boundaries.

The end-game of the supply and demand model is to analyze if markets are functioning properly. There are two ways to look at this. First, you can look at whether or not the market is balanced, or in equilibrium. This is when prices and quantities tend to be stable over time. In this case, the markets are neither in surplus, or in shortage. There is not too much product on the market, nor to little. If the market is balanced, economists will say that the markets have cleared. This first aspect is part of what we call positive economics, where we discuss how systems work.

3 Market Conditions

If the quantity demanded on the market is equal to the quantity supplied, we call this market condition equilibrium.

Qd = Qs Equilibrium

If the quantity demanded on the market is smaller than quantity supplied, we call this market condition a surplus.

Qd < Qs Surplus

If the quantity demanded on the market is greater than quantity supplied, we call this market condition a shortage.

Qd > Qs Shortage

Another aspect to think about, is whether or not the market price and market quantity, are socially acceptable. This second aspect is part of normative economics, where we discuss how systems should work. The main question is: are there enough units of the product for people to be satisfied? For example, the market for housing might be balanced, but there might not be enough homes for everyone in society. Another example, the market for automobiles might not be in surplus, but there might too many cars on the roads, creating traffic and air pollution.

Measuring the size of the disequilibrium

The simplest way to measure the size of a disequilibrium, is to consider the units of quantity. The formula is quite simple:

Disequilibrium = Qs - Qd

The result will be negative when there is a shortage, when product is missing from the needs of the consumers.

The result will be positive when there is a surplus, when product is unsold and sitting on shelves or rotting away.

| Product |

Qs |

Qd |

Disequilibrium |

Market Condition |

| Shoes |

500 |

600 |

-100 |

shortage |

| Computers |

20,000 |

18,000 |

2,000 |

surplus |

| Cribs |

800 |

920 |

-120 |

shortage |

-

Assumptions about price arbitrage

Marshall assumes that all of the product will be sold at the same price, no matter who buys it, or how much they purchase. This is a pretty strong assumption, because in real life, sometimes people negotiate, and sometimes it helps to get a better price, when you buy a larger quantity. Marshall was trying to build a model using mathematics, which was a new and cutting-edge thing to do in the early 1900’s. It would be a little bit more difficult to model an industry where all sorts of contracts could be negotiated at different prices. That’s not to say it does not happen in real life. Some industries function this way. Sometimes long-held relationships allow for preferential pricing. Sometimes volume gets a rebate. Sometimes timing makes a difference. Real life has a way of being full of quirks.

The point of a model, however, is to run simulations based on logic. In this case, quirks can get in the way, so economists prefer simplifying assumptions. In this model, there is a single price for every transaction, and if you were curious to know, it is imposed by a binding disinterested arbiter. Also, the model assumes that prices determine the behaviour of buyers and sellers on the market. In other words, quantities demanded, and quantities supplied, are both a function of the product’s price.

-

Assumptions about buyers and sellers

The supply and demand model assumes that buyers and sellers will do what’s in their best interest. For example, buyers will purchase more product if it becomes less expensive. The model also assumes that sellers will supply more product if its price increases.

These assumptions of rational behaviour are the object of much debate in economics, whereas some see the assumptions as being quite strong statements about how people should act, rather than depict how people actually behave in reality. Arguments over rationality tend be quite heated, really (see Goodman et. al., chapter 4 for a recent discussion of contributions from behavioural economists). Try to explain to a dog lover, that pets are not a rational choice.

Nonetheless, the model needs these assumptions to hold true. Because these behaviours are consistently going in opposite directions, both price, and production levels have to stabilize. We will explain this in more detail later.

-

Types of industrial structure

The supply and demand model allows the economist to analyze scenarios where sellers have more or less power on the market. The level of power depends on the type of industry and the structure of firms within the industry. Let's define a few terms before discussing further.

Commodity

A good or service which is indistinguishable, or non-differentiated, from other products on the market. Standardized products that are perfect substitutes no matter the producer. Ex: raw materials, vegetables, staple foods, etc.

Differentiated products

A good or service which is distinguishable, or differentiated, from other products on the market. Non-standardized products that are not perfect substitutes with output from other producers. Ex: custom materials, personalized services, creative meal recipes, hybrid products.

Industry

A group of producers who make similar products. The scale of the group can vary according to the shocks studied. The firms included should be affected similarly by an outside effect.

Monopoly

A situation where one firm produces all the goods in the industry.

Competition

A situation where each firm produces a small share of the goods in the industry.

The first element to define here is the scope of the group of producers we are going to analyze. An industry is a group of producers who have something in common, most often they produce a very similar good, and have to compete with each other on that market.

Economists can use the definition of the good to create an industry, but often the products are similar but not quite the same. Goods that are the same are called commodities. An example would be a 2X4 piece of lumber. In this case, all of the producers are part of the same industry.

Goods that are somewhat similar, somewhat substitutable, but different, are called differentiated. An example would be the Subaru Outback automobile. An economist studying the general automobile industry would include this model into the industry. However, an economist studying the small-car sedan market may be tempted to exclude it because it can be considered a small truck, or sport utility vehicle (SUV). Another economist studying the SUV market might be inclined to exclude it because it can be considered a station-wagon sedan. The Outback is a hybrid of both SUV and sedan characteristics, which makes it a very appreciated vehicle in its market segment. This hybrid nature is however a little bit of a puzzle for analysts.

So who do you decide what to include, and what to exclude? Economists will usually group firms together if their production would be similarly affected by a change in policy or market conditions.

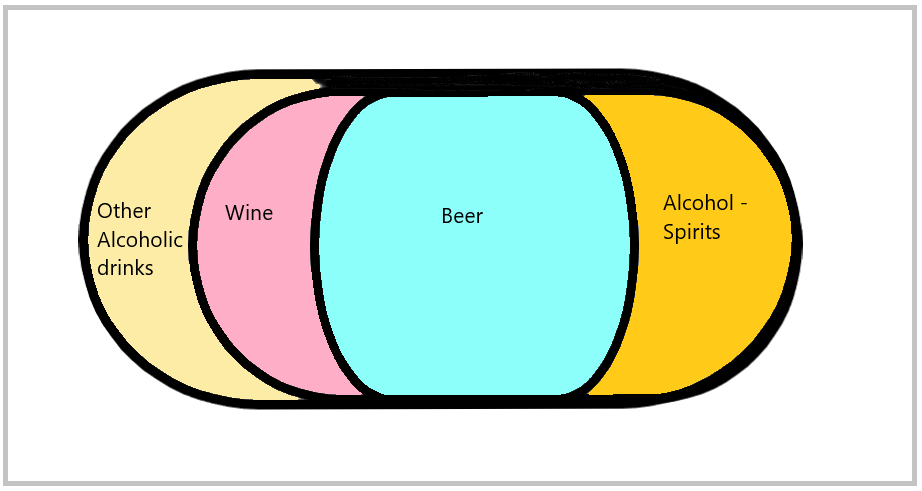

For example, a tax on beverages would affect all beverage makers, whether they produce soda pop, juice, milk, beer, wine, or spirits. But a change in consumer preferences for alcoholic drinks would not affect each beverage producer the same way. This is going to affect different kinds of alcohol. Sometimes it's ok to aggregate the firms and sometimes you need to make smaller categories.

Imagine there are four categories of alcoholic drinks: spirits, beer, wine, and others (including mixers, cider, and any other product). The industry you are studying depends on which products are similar enough to each other to be included in the same group. This depends on the types of variations you are going to analyze. The following diagram includes all alcoholic drinks, but you can imagine that each of these four categories can be subdivided. For example, wine can be divided into reds, whites, rosés, and sparkling. Beer can be divided into stouts, lagers, pilsners, weissens, honey browns, belgian whites, and others. Spirits can be divided into whiskeys, scotches, vodkas, gins, sherrys, sakes, and others.

Beverage industry diagram

In terms of industrial structure, when there is only one seller, we call this situation a Monopoly. In this case, you can imagine the seller will increase prices to maximize their profits. For consumers, this is not the best situation. It is also not the best solution for other suppliers because they are excluded from the market.

Ideally, the industrial structure that provides the most product, at the best price, is called Perfect Competition. In this case there are lots of sellers, and lots of buyers, and the price is as fair as possible.

Another, very interesting category, is an industrial structure called Monopolistic Competition. In this situation, a producer has invented a differentiated product which allows them to reduce direct competition. However, the product is still a close substitute to other offerings, so that the firm cannot abuse of a true monopoly position.

-

Dealing with outside forces

The model’s main strength is not so much that it predicts a stable price, an equilibrium, but that it allows analysts to deal with changes coming from outside forces. The model allows you to sort all of the variables that could affect the economy, or an industry in particular, and predict the ripple effects of an outside shock on the market.

Some of these shocks can be political, like the election of a new government which brings new types of regulations. Other shocks can be from related markets, such as inputs, or specialized services. Whatever the shock, the model helps to make a smart prediction.

Cheat Sheet

Quantity supplied

A quantity of product that is supplied by sellers.

Quantity demanded

A quantity of product that is demanded by buyers.

Industrial Structure

The type of industry power dynamic depending on the level of competition.

References and Further Reading

Goodwin, N., Harris, J. M., Nelson, J. A., Rajkarnikar, P. J., Roach, B., & Torras, M. (2018). Microeconomics in Context, 4th Edition. Routledge.

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics.

No Comments