Monetary Policy

Why Should I Care?

When the Bank of Canada prints too much money, we are all the poorer. But if money is insufficient, it's very difficult to obtain loans to buy a home, or start a business. We have to get this right.

This Lecture Has 4 Parts

- Definition of Monetary Policy

- Tools of Monetary Policy

- Simple Quantity of Money Theory

- Effectiveness

What is Monetary Policy?

Managing money supply is not the job of politicians. They would be easily tempted to run the printing press and create havoc with rampant hyperinflation. That’s why we give independence to central banks, such as the Bank of Canada (BoC), and ask the impartial men and women at its helm to govern monetary policy.

-

Definition of Monetary Policy

Monetary Policy refers to actions taken by the central bank to change the money supply in order to achieve economic objectives.

These objectives are:

- To ensure low levels of inflation

- To maintain high levels of production and employment

- To avoid an imbalance of international trade and payments.

In Canada, the explicit mandate of the Bank of Canada is to contribute to the economic well-being of Canadians, by overseeing monetary policy, the financial system, the currency, and federal funds management.

In regards to monetary policy, the objective is to preserve the confidence of Canadians in the value of the currency, by maintaining inflation at a low rate, which is stable and predictable. Contrary to the USA’s Federal Reserve, Canada’s central bank has no mandate to achieve full-employment.

-

Tools of Monetary Policy

Monetary policymakers have essentially three tools: changes to the overnight interest rate, open-market bond transactions, and direct deposits to bank accounts.

The Policy Interest Rate, also known as the Overnight Rate, the Target Rate, or the Key Bank Rate, is the interest rate the Bank of Canada charges on its loans. These loans are granted to commercial banks only. They usually contract these loans amongst themselves on the overnight loan market, at the end of a given day when they need extra cash to balance their financial statements. The money is paid back the next morning with fresh money from new deposits. However, if the private overnight loan market is using an interest rate that is too high, or too low, the Bank of Canada can intervene until the market interest rate matches the Bank Rate. This is where the open-market bond transactions, and the direct deposits come into play. This being said, the most important objective of the central bank is to manage the rate of inflation. Changes to any of its tools is directed by inflation pressures.

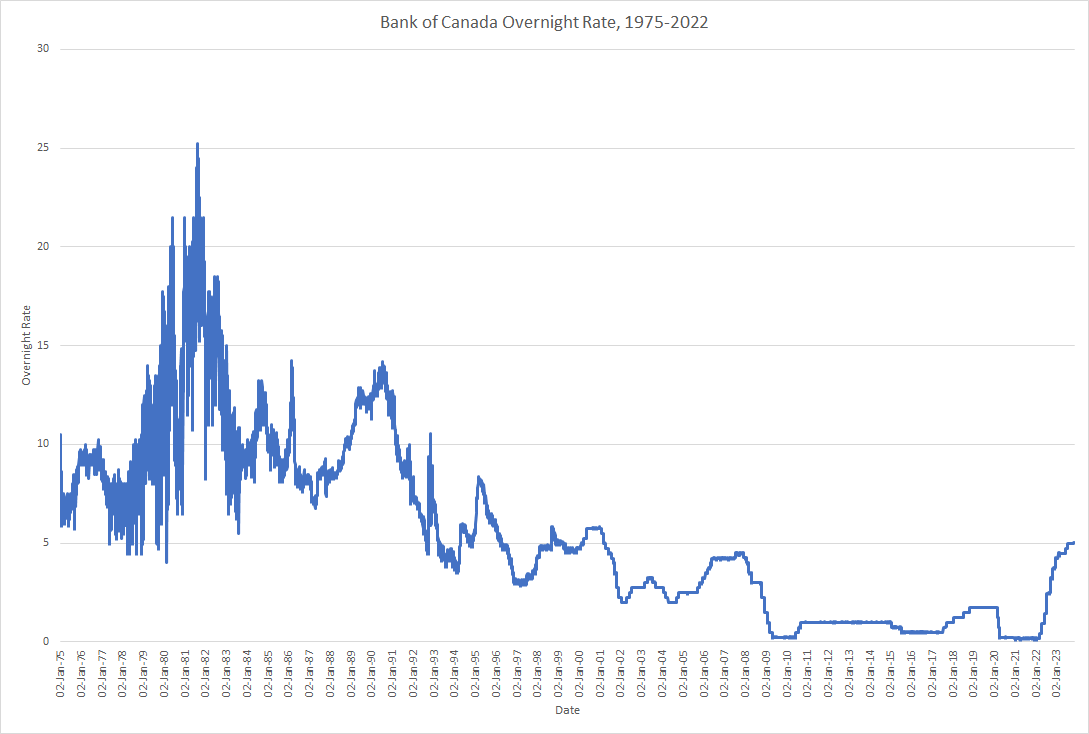

As you can see on the graph below, the overnight rate has been steadily decreasing since the turbulent 1980's. Recently, the bank has been increasing the rate to stem inflation which had not gone over 3 percent annual rate of increase since the 1990's.

Graph - Overnight Lending Rate since 1975

Source: Statistics Canada, Table : 10-10-0139-01, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1010013901

In Canada, the guiding principles for inflation measurement are the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for long-term variations, and the core measurement of CPI for short-term variations. Core CPI excludes the most volatile industries at any given time. The BoC tolerates inflation between 1 and 3 percent, aiming at a 2 percent target. This means that if inflation rates were to be lower than 1 percent, then the BoC would apply expansionary monetary policy to stimulate the economy. If the inflation rates were to be higher than 3 percent, it would apply restrictive monetary policy to cool the economy down.

The Bank Rate is usually the lowest interest rate in the land. Why? Simply put, banks have to pay this as a basic cost of doing business. They cannot charge a lower interest rate to their other clients, or they won’t make a profit. Hence, if the Overnight Rate changes, all the other interest rates in the economy will also change in the same direction.

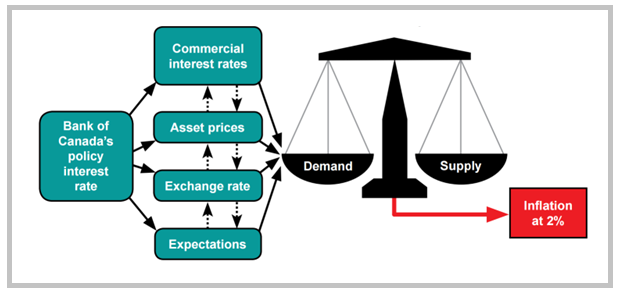

In terms of enacting monetary policy, the Bank of Canada uses a technique called interest-rate targeting, rather than direct money-supply management. With interest-rate targeting, the first move is to modify the overnight rate. This acts as a signal, which allows the quantity demanded for money to adjust. Investors and home buyers change their minds about their demand for loans, given the new price. The diagram below shows how many relationships are in play. The Bank Rate directly affects the prices of financial products (in green) across the economy, notably the following elements:

- Commercial interest rates

(corporate loans, mortgages, car loans, etc.) - Asset prices

(houses, condos, buildings, corporate stocks and bonds - Exchange rates

(CAD to USD, EURO, GBP, YEN, etc.) - Expectations

(Consumer confidence, Investor confidence, Predicting earnings/losses)

These elements are inter-related. For example, Expectations can affect Exchange rates, Asset prices and Commercial interest rates. In return, these changes can modify Expectations.

The outcomes in aggregate measurements of each of these elements will modify volumes of sales, production and revenue, in the production economy (in black). Finally, the outcome of the production economy determines prices for goods and services offered to consumers. Hopefully, the system does not show price inflation above 2 percent per year.

Diagram - Using the Bank Rate to affect markets and inflation

Source: Bank of Canada.

Since there are so many people involved, the overall price-sensitivity of demand for money is difficult to predict accurately. So it's become well understood by economists that it is better to let demand reveal itself when faced with a new price, in this case, the price of money is the interest rate on loans.

Once demand is revealed, the bank will actively modify money supply to match the needed funds. Since the Canadian dollar is a fiat currency, the central bank can modify money supply without increasing or decreasing holdings of gold or other assets. The central bank can do two things: 1) modify bank deposits in its accounts, 2) buy or sell bonds on the money market. The central bank will usually do both, but the extent to which it uses deposits, or bond transactions depends on its financial situation and market conditions at the time of designing the policy.

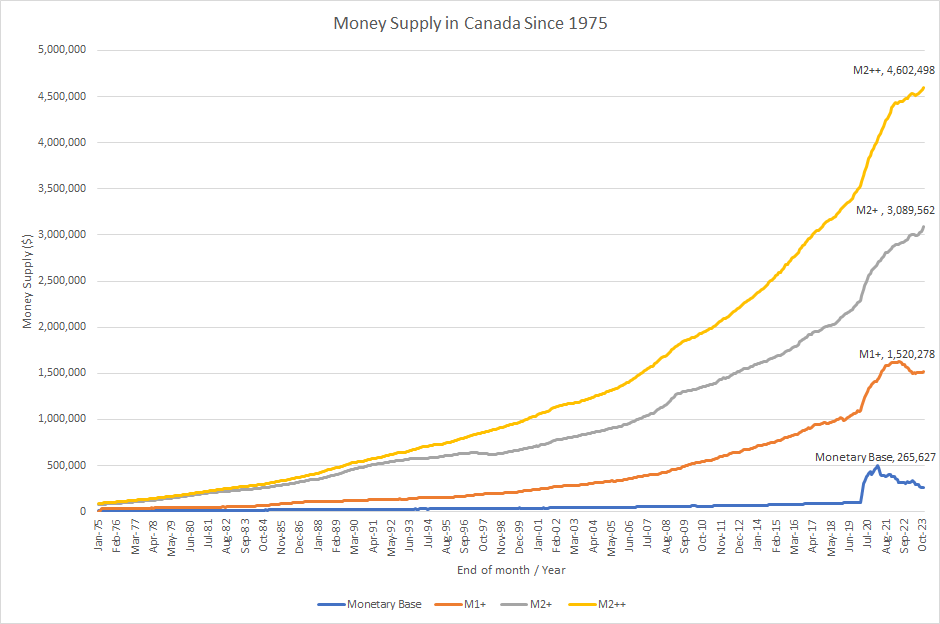

The following graph shows just how much money was added to the financial system during the COVID-19 pandemic. If you look carefully at the Monetary Base, which includes cash and chequing accounts, the stock of base money shot from 104 B$ in March 2020, to 262 B$ in April, and 361 B$ in June. These increases are unheard of outside of war times. The stimulus tops out in March of 2021, at 497 B$, at five times the amount of hard money circulating in the economy as a year earlier. Since the end of the pandemic, Monetary Base has been culled, and sits now (Dec. 2023), at 265 B$.

Graph - Money Supply in Canada since 1975

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 10-10-0116-01. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1010011601

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 10-10-0116-01. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1010011601

The graph also shows a few more curves. These represent different versions of money pools in Canada, and usually represent a wider definition of money as the pools include more types of bank accounts.

The second curve, M1+, is a monetary aggregate that includes the Monetary Base, plus chartered bank chequable deposits, chequable deposits at trust and mortgage loan companies, and chequable deposits at credit unions and caisses populaires. M1+ is a comprehensive measurement of money sitting in accounts that are liquid. These accounts can be used for purchases on an instant notice. You can see that the massive increase in Monetary Base has spurred a sudden increase in M1+. This is due to all of the cheques and subsidies awarded during the pandemic. The decrease in Monetary Base, coupled to increases in the interest rates in 2022-23 have had an effect. M1+ peaked in May 2022 at 1.62 T$ and now sits a little lower, at 1.52 T$.

The third curve is M2+, which is a monetary aggregate that casts a much wider net. M2+ includes almost all of the available funds in the economy. It includes paper money, coins, and money in circulation in personal chequing accounts, savings accounts, as well as deposits at trust and mortgage loan companies, caisses populaires and credit unions, life insurance company individual annuities, government owned savings institutions and money market mutual funds. The graph below shows that money supply in Canada is growing very robustly, even more so since the COVID pandemic. Contrary to the Monetary Base, which is controlled by the Bank of Canada, general money supply in Canada has not contracted in response to higher interest rates since 2022. M2+ sits at 3.09 T$ (Dec. 2023).

The last curve is the M2++, which represents all of the liquid, but also all of the non-liquid funds, such as investments in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other securities such as Canada Savings Bonds. It has increased steeply at the beginning of the pandemic, and has not declined since. It now sits at 4.6 T$ (Dec. 2023), which represents more than twice Canada's GDP.

Economists usually consider that a change in monetary policy takes anywhere from 9 months to 24 months to work its way through financial markets into the producing economy. This means that the changes in the monetary aggregates are lagged between each other. Monetary Base has been decreasing since April 2021, but it's effect on M1+ was felt only in November 2022. It took 18 months. The decrease in Monetary Base may also affect the larger aggregates later, but that remains to be seen.

Until 1995, the Bank of Canada was actively managing money supply, and letting the financial markets set the interest rate. The hard facts of economics is that you can't set both the quantity and the price of any product, even if you are a monopoly, as is the case here for a central bank.

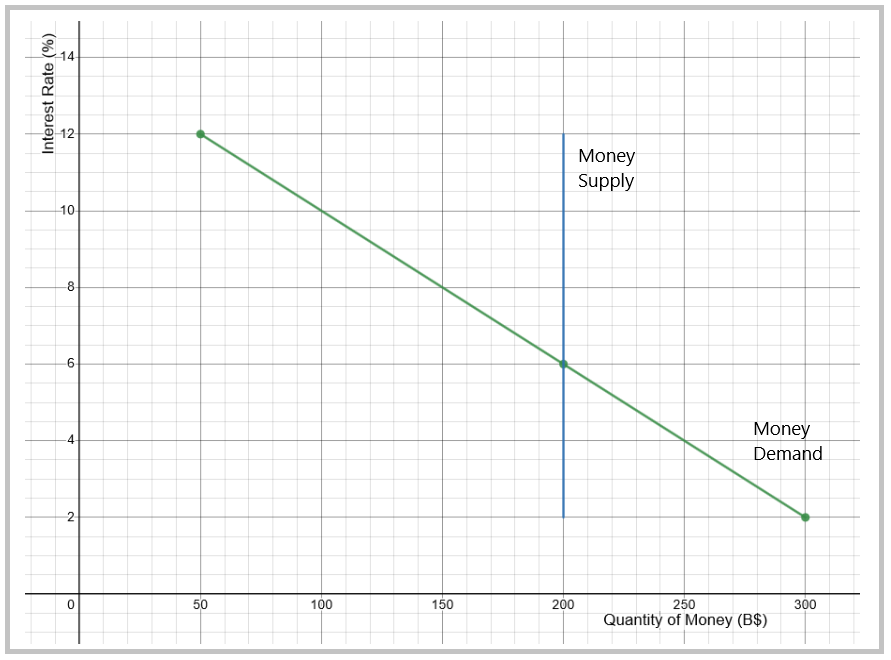

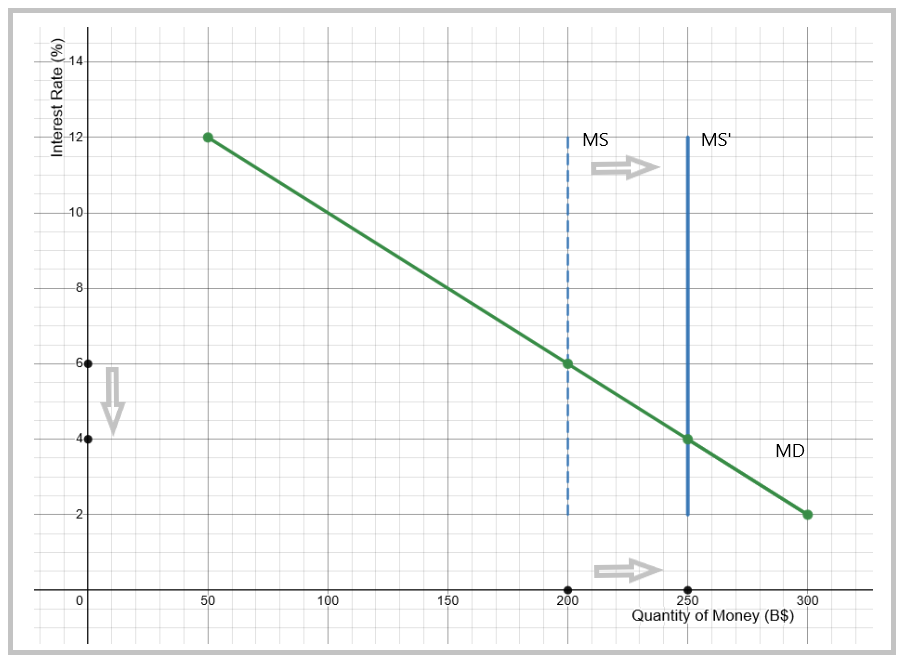

The following graph shows the basic curves of the money market, where interest rates are set by the central bank, and so is the supply of currency. The slope and position of the demand curve is the main parameter which is out of the hands of central bankers. In a central banking situation, the money supply is therefore a vertical line, which shifts left to right as the central bank acts on markets to decrease or increase the supply. The demand for money is a function of the interest rate, which is in effect the price for loanable funds.

Graph - The Money Market

Acting to grow the economy

The following graph shows an example of a decrease in the overnight rate, as the main strategy to implement an expansionary monetary policy. This kind of policy would only be in effect if the annual inflation rate was below 1 percent or actually negative.

The first action is for the central bank to reduce the overnight rate, from 6 to 4 percent. Keep in mind that this example is using fictional yet realistic values for the Canadian economy. This creates a shortage of money, since at this lower price, quantity demanded is more important. In this example, MD increases from 200 billion dollars (B$), to 250 B$. Since Canadian currency is fiat, it is not produced by free-market suppliers. It's supply is fixed by the BoC.

The second action happens once consumers and investors realize that the interest rate has fallen. The central bank increases the supply of money and the MS curve shifts right, to clear the shortage of loanable funds.

Graph - How an Decrease in the Policy Interest Rate Affects Money Supply

The 50 B$ shortage means that people and corporations were lining up at banks for more and/or bigger loans. In Canada, the banks can create the money, but they need to respect currency reserve ratios. So in effect, they can't write up new loans unless the central bank gives them some financial room to do so. This is where the direct actions come in. The Bank of Canada now knows that it needs to increase money supply by 50 B$. It will increase deposits in chartered bank accounts at the BoC, and it will buy bonds from the money market (selling cash in return, thus increasing money supply). By the way, the BoC does not need to create 50 B$ of new cash, to create 50 B$ of Money Supply. There is a monetary multiplier effect, which is something we will leave to more advanced courses in monetary theory.

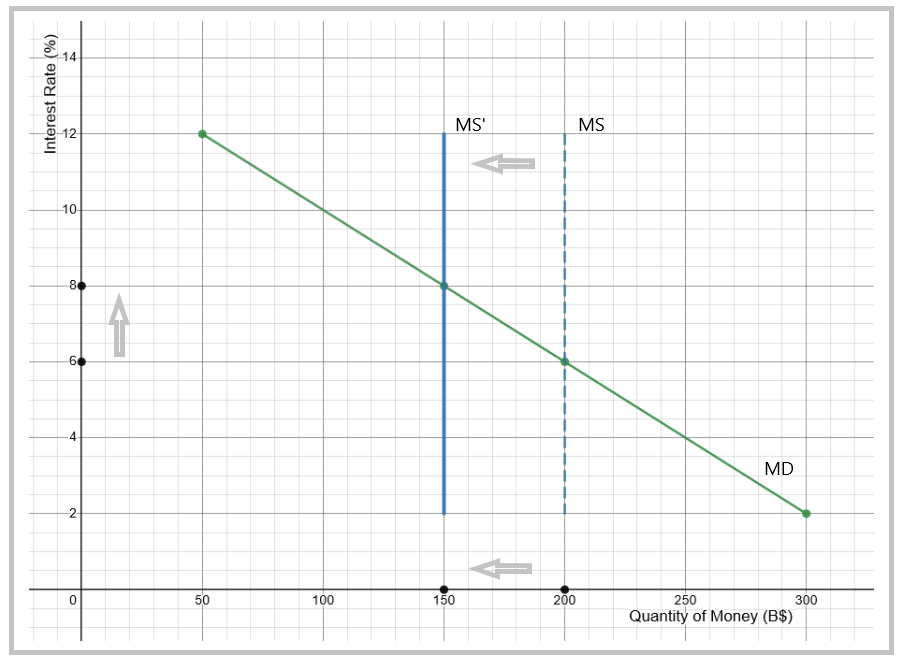

Acting to slow the economy

The following graph shows an example of an increase in the overnight rate, as the main strategy to implement an restrictive monetary policy. This would be in effect if the annual inflation rate was above 3 percent.

The first action is for the central bank to increase the overnight rate, from 6 to 8 percent (this example is using fictional values but realistic for the Canadian economy). This creates a surplus of money, since at this higher price, quantity demanded is less important. In this example, Qd decreases from 200 B$ to 150 B$.

The second action happens once consumers and investors realize that the interest rate has increased. The central bank decreases the supply of money and the MS curve shifts left, to clear the surplus of loanable funds.

Graph - How an Increase in the Policy Interest Rate Affects Money Supply

The 50 B$ surplus means that people and corporations are no longer asking banks for loans. Many investment projects are put on hold. In Canada, the banks don't want to hold money that is not lent out for profit. This is where the direct actions come in. The BoC now knows that it needs to decrease money supply by 100 B$. It will decrease deposits in chartered bank accounts at the BoC, and it will sell bonds on the money market (buying cash in return, thus decreasing money supply).

Rate Targeting Is More Efficient

When you look at these graphs, you might be tempted to ask yourself why the BoC prefers to move interest rates first, rather than just shift the money supply curve. This is called Rate Targeting.

The answer is: ''been there, done that.''

Through the 1970's and 1980's, the BoC would act on financial markets and let banks figure out the overnight lending rate. It was hard to execute that policy because it is difficult to estimate the monetary multiplier, and the slope of the demand curve. Those decades were notoriously hard to manage, with inflation rates as high as 12.5 percent in 1981, and mortgage interest rates as high as 22 percent.

You might be tempted to believe that clever use of statistics and scientific methods would have solved that, but empirical evidence has shown that it is much more efficient to move the interest rate first, and let demanders reveal their preferences. The move to interest-rate targeting in 1994 marked the end of inflation in Canada for almost three decades. Canada's central bank now has a solid international reputation for providing a stable price environment, which investors appreciate.

What is Quantitative Easing?

You might have heard the expression 'Quantitative Easing' in a podcast or TV clip on a business news channel. The term came out in 2008, when the US and Canada were going through a major recession. Many companies went bankrupt, such as the Lehman Brothers bank, and many others were teetering on the edge, such as General Motors and Chrysler Motors. The Obama administration actually purchased GM and Chrysler, as did the Harper government for the Canadian assets of these companies, to avoid their bankruptcy.

Amid this financial disaster, the central banks resorted to purchasing trillions of assets from financial markets, and held on to them until the economy recovered. This was called 'Quantitative Easing', or QE, because the central banks felt that moving interest rates down was not potent enough to fix financial markets and get the economy out of recession. Central banks had also used traditional transactions on bond markets, and they deemed them insufficient. QE involves purchasing assets which are less liquid, and part of 'broad money', or outside the 'narrow money' of the Monetary Base.

QE is a modern toolbox response to monetary issues which is derived from the recent changes to money creation. Central banks are no longer responsible for creating money, as they had done in most of the post-WWII period. The following video explains the modern role of central banks and the effects of QE in monetary policy.

VIDEO - Money Creation in the Modern Economy

-

Simple Quantity of Money Theory

For most economists, monetary policy is the strongest (and most potentially harmful) means of government intervention. Keynes famously quipped that money was not that important. His most important critic, Milton Friedman, later argued quite convincingly that mismanaging money supply was the main reason that the 1929 stock market crash turned into a major decade-long depression.

The main question is: Do changes on the financial markets affect the production economy?

The answer is: it depends on the business cycle phase, and also on which economist answers the question.

For conservative economists, who might identify with the Marginalist, Monetarist and/or Austrian schools of thought, monetary policy can do way more harm than good. The main temptation for any manager of a fiat currency, that is, a currency you can print to no end, is to do just that. If you increase the supply of any product, its value decreases. And with fiat money, because it has no intrinsic value, other than to be a means of exchange, it's value can drop to nothing. In this case, the sticker price of goods and services increases dramatically to cover the drop in value of the currency.

The formal presentation of this idea can be summarized in a neat, and very useful, equation. It is called the simple quantity of money theory.

M * V = P * Q

Where

M = stock of money supply

V = velocity (flow of money)

P = price level

Q = quantity of production (flow)

and

Output = Sum of (Pi * Qi)

In essence, P*Q measures output, and can be replaced by real GDP. Money supply is known and accounted for. Velocity is a variable that has no direct measurement, and is not observable outside of this model. Velocity represents the churn rate of the stock of money in the economy to account for all of the transactions that need to take place to produce real GDP (sum of P*Q).

Getting back to the equation, if M increases, and V is held constant, then simple algebra dictates that P*Q must increase. Conservatives, especially Austrians, assume that increasing money supply is not a productive investment because it does not increase the economy's physical capital, or labour, which could help produce more output. If this is true, we hold Q constant as well. The end conclusion is that any increase in the stock of money, will directly increase prices, thus we call it inflationary.

if M * V = P * Q,

and if V and Q are constant,

then an increase in M must generate an increase in P.

The model works the same way in reverse, when you apply a restrictive monetary policy. If you reduce the stock of currency, prices will decrease.

For conservative economists, monetary policy does not transmit to the productive economy and so its effects on prices are the only real effects. Inflation is thus the product of mismanaging a fiat currency. There is truth to this because most of our inflationary periods have been under fiat regimes. Some conservatives will argue for gold-standard central-banking, or even free-banking, instead of fiat central-banking, and in the case of central-banking they will argue for strict use of policy to avoid hyperinflation.

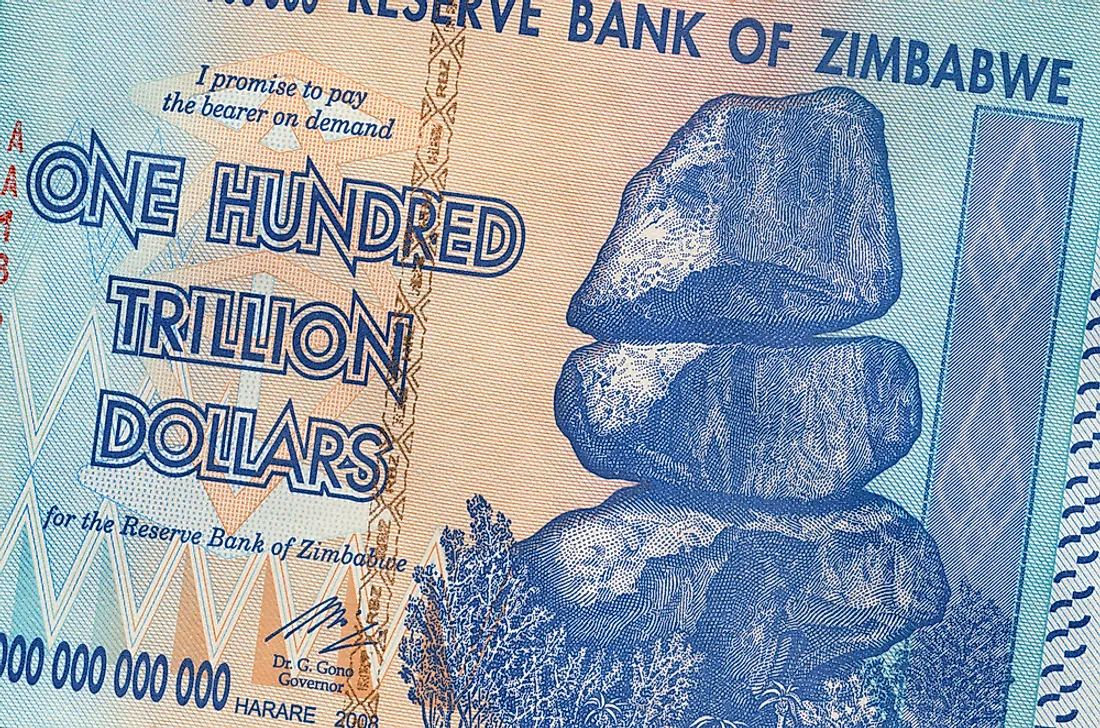

Hyperinflation: It's Not Always Money's Fault If Your Economy Was A Mess

There is a misunderstanding about the root cause of hyperinflation. If you look at most of the well-known cases, such as 1918 Weimar Republic, or 2005 Zimbabwe, the country's economic conditions were awful, prior to the expansionary policy of fiat money printing. Often, these countries were hit by severe supply-side shocks, such as war bombing of productive capacity, or a sudden deterioration of international trade. When the exchange rate drops suddenly, the country is effectively importing inflation, since all of the imports are more expensive. There is usually a historically traceable presence of inflation prior to the central bank's intervention. Unfortunately, if you apply expansionary monetary policy to a backward economy where inflation is already present, nothing good can come of it, really.

So, it is true that printing money is inflationary, but cases of hyperinflation usually are rooted in very deeply set structural issues. Printing money is certainly not the solution, but often it is seen as the last resort policymakers have, in their toolbox to keep their institutions paying out salaries and keeping their proverbial boat floating.

Another issue with over-printing is that of war. Historically, central banks have loosened their rule-book on printing money during times of war. It was the case in Britain on several occasions, notably World War I, and World War II, but also in Canada and the US. Wars are notoriously unproductive, and costly, creating constant needs for more weaponry and vehicles destined for destruction. When countries are faced with the prospect of losing war, they do not hesitate to lift monetary rules, or even the gold-standard.

For Keynesian economists, policy depends on the phase of the business cycle. Debates are plentiful on details, but in essence, Keynesians will agree with the quantity of money theory if the output level is equal to potential. The point of intervention is to help the economy when it's off its potential, such as in a recession, so there's an argument here in favor of monetary policy. Remember that fiscal policy requires the approval of public opinion and its elected representatives. That makes it a little slower to execute than it is for the board of a central bank to meet and act on interest rates.

-

Effectiveness

It is difficult to generate hard scientific evidence as to how effective monetary policy is, if you compare empirical work in economics with other disciplines such as psychology or chemistry. These scientists use laboratories to test the effects of a stimuli on real people, or real elements of nature. This is almost impossible to do in economics. This being said, there are lots of historical case studies over the past centuries, about money and fiat currencies. These cases can be studied as natural experiments. Hyperinflation is such an important topic that economists have studied its many incidences, and provide confident arguments about when monetary policy works well, and when it does not.

Economists usually agree that monetary policy works better on the way down. It's easier to slow down the economy, than it is to grow it. Hikes in interest rates will usually have a quicker and more important impact on the economy, compared to reductions in interest rates. This means that restrictive monetary policy is more effective than expansionary monetary policy.

The first reason is that bankers prefer to follow suit on a rate hike quickly, because if they don’t their margins are squeezed. Inversely, bankers might take more time to implement rate reductions because their margins are now larger and they want to benefit from this lucrative situation. The speed of adoption will depend on the level of competition in the banking sector.

Second, investors are highly sensitive to rate hikes, but they might not be immediately interested by a rate reduction. This is especially true of business investment in capital goods (machines, equipment and plants). A rate reduction is enticing, but above all else, investors need a worthy project. The existence of these projects is a function of many factors such as consumer demand, industry cycles, innovation, political stability, expectations of demand and perceived profitability.

Liquidity Trap: Monetary Policy is useless, according to Keynes, in the extreme event of a very drastic recession. In this situation, when the overnight rate has been lowered regularly, demand for savings overwhelms the financial system. In this case, the AS curve is completely flat, as people prefer to hold cash, rather than loanable funds (investments). Investors and ordinary citizens prefer to hoard cash, than to deposit their money in interest-based savings accounts, term deposits or even bonds. At this point, an interest rate decrease does not grow money supply because “Cash is King”.

Policies Must Work Together: Fiscal and monetary policies must work hand in hand to grow or slow the economy. This may not be the case because Parliament, which decides fiscal policy, does not control the Bank of Canada, which plans and executes monetary policy.

Not Region-Specific: Monetary Policy is not region specific, and a single monetary unit may hurt/help different regions according to cycles. A contractionary policy aimed at cooling off Alberta or Ontario, could hurt another region, such as the Maritimes, which needs expansionary policy to grow out of structural unemployment.

Overall, the main historical lessons of monetary policy are:

1. Don't print too much money.

2. Don't add money supply when the economy is hit with a supply-side shock.

3. Don't shrink money supply when the economy is hit with a demand-side recession.

4. It's easier to fix interest rates, than the quantity of money.

Summary Table

|

|

Expansionary Monetary Policy |

Contractionary Monetary Policy |

|

What? |

Interest rates (i) ↓ MS ↑ |

i ↑ MS ↓ |

|

Why? |

To Create Jobs |

To Reduce Inflation |

|

Who? |

Bank of Canada |

Bank of Canada |

|

When? |

Recession |

Over-heating |

|

How? |

More loanable funds, more investment, AE increases, Y increases. |

Less loanable funds, less investment, |

|

Pros |

No budget deficit. Affordable. |

No Political Pain. Works. |

|

Cons |

Inflationary. Not region specific. |

Lack of coordination with fiscal policy. |

Wrap-Up

Monetary Policy refers to measures taken by the central bank to manage the supply of money in the economy. Its objective is to keep stability in prices, output, and foreign exchange rates.

Tools are open-market transactions, direct deposits in accounts at commercial banks, and changes to the overnight rate.

These measures wind up in GDP through changes to the amounts of loans, and investments such as new equipment, or new homes.

Tight, restrictive or contractionary monetary policy is very effective to cool the economy down. But it is uncertain that loose, or expansionary, monetary policy is very effective to increase GDP.

Cheat Sheet

Expansionary Monetary Policy:

A policy designed and executed by the central bank to increase the money supply when the economy is in recession.

Contractionary Monetary Policy:

A policy designed and executed by the central bank to decrease the money supply when the economy is over-heating.

Quantitative Easing:

Operations of the central bank on financial markets to purchase assets and contribute to expansionary policy.

Policy Interest Rate:

The interest rate charged by the central bank to other private banks for their overnight borrowing needs. This rate determines the floor of interest rates across the financial industry.

References and Further Reading

Bernanke, B. S. (2022). 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19. WW Norton.

Binnhammer, H. H., & Sephton, P. S. (2001). Money, Banking, and the Canadian Financial System, Eighth Edition. Toronto: Nelson Thomson Learning.

Cagan, P. (1956). The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation. https://fr.scribd.com/document/373295145/Phillip-Cagan-1956-The-Monetary-Dynamics-of-Hyperinflation-pdf

Hanke, S. (2017). Hyperinflation: Much Talked About, Little Understood. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevehanke/2017/10/31/hyperinflation-much-talked-about-little-understood/?sh=3e1569823944

Liping, H. (2017). Hyperinflation: A World History. Routledge.

McLeay, M., Radia, A., & Thomas, R. (2014). Money creation in the modern economy. Bank of England, Monetary Analysis Directorate. Quarterly Bulletin, Q1. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Molico, M. (2019). Researching the Economic Impacts of Climate Change. Ottawa: Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2019/11/researching-economic-impacts-climate-change/

No Comments