Labour Markets

Why Should I Care?

The level of employment determines how wealthy most people are. Not having a job often means hardship and poverty. If too many people don’t work, this affects the whole economy.

This Lecture Has 4 Parts

- The Labour Force

- Unemployment

- The Unemployment Rate

- The Participation Rate

What are Labour Markets?

Labour markets are social constructions, “places” where regular people exchange their labour, their physical and/or mental efforts, in exchange for money (wages). These markets are somewhat imperfect. Supply of labour from workers does not always match demand from employers. Market type varies but most people face a “one-to-all” scenario. There are usually a lot more workers than employers.

Why do employment levels vary in the first place?

Labour is the only resource to be variable in short-run. If sales drop, employers cannot shrink their machines, but they can cut their payroll.

-

The Labour Force

The Labour Force is a population of people who are available to work, or already have a job. In Canada, the Labour Force data are determined monthly by survey (sample data). Statistics Canada publishes the Labour Force Survey for Provinces and large cities. More accurate data, available for smaller communities, is available once every five-years in the Census program.

The Labour Force values are deducted from people’s occupations. It includes people who are working (Employed), and people who are not working, but looking for a job (Unemployed). They are both considered Active.

People excluded from the Labour Force are considered Inactive: this includes stay at home parents, retirees, disabled people, full-time students, welfare recipients, and rich people who don’t want to work.

A few exceptions: full-time students with part-time jobs, and parents on paid parental leave, are considered Employed by Statistics Canada. The surveyed population does not include all Canadians. It excludes prisoners, priests and clergy, military personnel, children 14 and under, and First Nations living on reserve.

Table - Labour Force Aggregate Values, January 2022

| K persons 15+ | Canada | Quebec | Ontario | Alberta | British Columbia |

| Population | 31 546.8 | 7 123.6 | 12 436.1 | 3 573.9 | 4 396.4 |

| Labour force | 20 189.3 | 4 464.9 | 7 973.4 | 2 441.8 | 2 812.9 |

| Employment | 18 819.9 | 4 198.0 | 7 387.1 | 2 262.1 | 2 662.4 |

| Unemployment | 1 369.4 | 266.9 | 586.3 | 179.7 | 150.5 |

| Not in labour force | 11 357.5 | 2 658.7 | 4 462.7 | 1 132.1 | 1 583.5 |

| Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0017-01 Labour force characteristics by sex and detailed age group, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality (x 1,000) | |||||

| https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410001701 |

|||||

As you can see from the table above, there were 18.8 million Canadians employed in January of 2022, which is more than half of the available population of Canadians aged 15 years or more. Of course, we don't need - or wish - for all of these Canadians to be working. Many people are retired, or decide not to offer their labour services on the market for other reasons. These ratios do matter of course because salaried income is the most important mechanism for wealth distribution in the country.

-

Unemployment

During economic downturns, there may be surpluses on the labour markets. This means there are too many workers for the jobs available. Economists will say this shows a low level of employment, and a corresponding high level of unemployment. Unemployment is the situation of being both jobless and looking for work.

Interview with Jean Francois Parent - on Unemployment

Types of unemployment are

Seasonal

Out of job because the season is over. Ex: Fishing, Forestry, Horticulture, Ski coach

Frictional

Out of job because of bad timing. Ex: graduate waits 9 months for opening

Cyclical

Out of job because of economic climate. Ex: laid off because sales are down

Structural

Out of job because of obsolescent production. Ex: Google News kills newspaper

Technological

Out of job because of process innovation. Ex: Automatic teller machines (ATM) replace bank tellers and cashiers

The unemployed represent a surplus of workers on the labour market. Workers are suppliers, so they are the supply curve. Firms are now buyers, so they are the demand curve. It’s a factor market, so the relationship is inversed with product markets. Unemployment is usually the result of a drop in demand from firms, who are reducing their production levels, or replacing workers by physical capital (robots, machinery, etc.). Keep in mind that the metrics for unemployment are based on humans as the main unit of measurement.

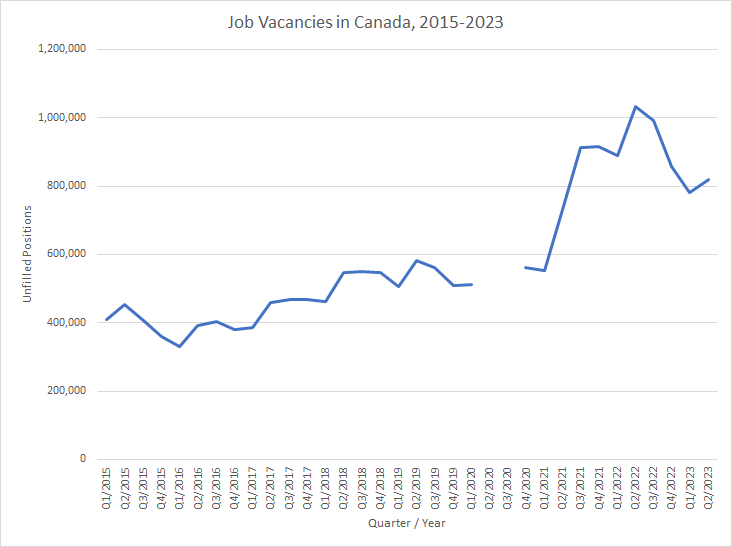

The opposite of unemployment is unfilled positions, which is becoming a very important issue in Canada. This is the measure of a shortage of workers on the labour market. The social ills associated to this issue are not as dramatic as poverty and anguish. However, it is causing lots of headaches for companies and managers who have a hard time filling their orders if they can't hire enough personnel. Statistics Canada has started measuring unfilled positions in 2015, under the variable Job Vacancies. As you can see from the graph below, job vacancies increased tremendously since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 (there is no data in Q1 and Q2 2020 because of the pandemic's effect on government operations). Keep in mind that Job Vacancies are not measuring humans, but administrative paperwork as the main unit of measurement. Many economists are weary about the using Job Vacancies data as the mirror expression of unemployment on the labour market.

Graph - Total Job Vacancies in Canada are on the Rise

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0326-01 Job vacancies, payroll employees, job vacancy rate, and average offered hourly wage by industry sector, quarterly, unadjusted for seasonality

-

What is the Unemployment Rate?

Aggregate values are useful for measuring trends. But if you want to compare across countries, provinces or industries, you need to use a rate (ratio or fraction). Each statistic will tell a different story, which we call interpretation in statistics. By comparing the number of people who are unemployment, to the total labour force, we get the Unemployment Rate (UR), which tells us how easy it is find work.

UR = Unemployed / Labour Force.

By the way, a ratio of 0.08 = 8 percent.

An increase in the unemployment rate (from 8 to 10%) indicates it is harder to find a job, as more people are jobless and looking for work. The media regularly report changes in the Unemployment rate because people care about how easy it is to find work or change jobs. Keep in mind that the unemployment can only measure surplus market conditions, and not shortages. This is why we need to use the Job Vacancies data in periods of labour shortages.

The Unemployment Rate will never be zero because of frictional unemployment. At “Full Employment”, the UR will be somewhere between 4 and 6 %. The UR will also never be negative, so it cannot measure labour shortages accurately. This is why we need a supplemental measurement of Job Vacancies, or Unfilled Positions.

In Canada, the unemployment rate has varied quite a bit over the years. The unemployment rate usually increases when the economy is in a slowdown, or recession. You can this happen see on the graph below, in the early 1980's, the early 1990's, in 2009-10, and more recently in 2020-21. There are also trends within the year. For example, the unemployment rate usually increases in the summer, decreases in september when children are back to school and parents are back to work. When comparing provinces, Alberta has historically enjoyed unemployment rates much lower than the Canadian average, while Quebec and the maritime provinces usually suffered higher rates. This trend has reversed recently since Quebec's labour market outcomes are consistently better than those of Ontario, BC and Alberta.

Graph - Unemployment Rate in Canada

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0017-01. Labour force characteristics by sex and detailed age group, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality (x 1,000). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410001701

As you can see on the graph, the unemployment rate for Canada jumped dramatically in April 2020. The highest rate recorded was 18.3 percent in Quebec, while the Canadian rate was 13.6 percent. The statistic dropped quite quickly afterwards for two reasons: A) the federal government introduced the famous Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and other new programs, and B) Statistics Canada considered someone on CERB to be in the active population and yet not looking for a job. One can only speculate what the unemployment rate would have been without programs like the CERB, however it seems fair to estimate that the rate would have hovered in the mid-teens for at least a 12-month period.

-

What is the Participation Rate?

The Participation Rate (PR) shows how big the labour force is. It shows how many people are participating in the labour market, relative to the adult population of the country.

Participation Rate = Labour Force / Adult Population.

Economists care about this because production levels depend on the quantity of available resources such as labour. Potential GDP depends on the Participation Rate. The mass media don’t report this statistic because it does not relate to citizen’s daily lives.

Interpreting trends

|

|

Population |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Labour Force |

Un. Rate |

Part. Rate |

|

2004 |

22 |

13 |

1 |

14 |

7.1 % |

63.6 % |

|

2005 |

23 |

13.5 |

1.5 |

15 |

10.0 % |

65.2 % |

As you can see from the table above, it is important to use both the UR and PR in your analysis of a labour market. In this particular country, the population has grown by 1 M people in 2005. Of that growth, half the increase were able to find a job, the other half are unemployed. The bad news is that the UR grew from 7.1 to 10 percent. It will be harder to find a job in 2005 than in 2004. The good news is that the PR increased by almost 2 percentage points to 65.2 percent. The country's capacity to produce has increased. If the country can integrate the unemployed into the labour market, the country's economic potential will be fulfilled.

Labour markets have to be analyzed with several statistics in order to understand what is exactly going on. Some labour markets have low unemployment rates, but that does not necessarily mean the economy is very strong, which we can see from a low participation rate.

-

Limitations

Labour markets can be performing at sub-par levels. Three problems are often hard to measure by regular statistics:

Underemployment is a situation where some people have a job for which they are over skilled. They would prefer to work in a better paid position but they cannot because of cyclical unemployment.

Discouraged workers don’t show up in the unemployment rate statistics because they have left the labour force. They used to look for work, but after several months – or years – have given up looking and stay at home living off someone else, or with a government aid program such as welfare payments.

Stagnant economies can have either high or low rates of unemployment. A low rate does not always mean it is easy to find work; it could mean that no one is looking for work because they have left the area to find work elsewhere. This is why economists pay more attention to changes in the unemployment rate over time, than its level at one point in time.

Green Policy

There are critical debates in economics about the impact of environmental regulations on employment levels. This is true, especially in countries, such as the USA and Canada, where so many jobs depend on highly polluting sectors such as mining and oil.

There are also many policy options to choose from and their effects on the economy can be hard to predict. For example, governments can ban production outright, as we have done with toxic inputs such as lead and asbestos. Governments can regulate quantities produced using quotas or production permits. Government can also tax a polluting product to discourage end-use consumers from purchasing the product.

To help policy makers, economists run simulations, which usually are called general equilibrium models, where some variables can be triggered to measure the inter-dependent effects on the other variables in the economic system. Economists can compare the effects of these types of interventions on the employment sectors of both the polluting industries, and the non-polluting industries.

In recent studies, it seems that the employment losses in newly-regulated industries would be absorbed by new work in the non-polluting industries. This effect does depend however on the type of policy used to reduce pollution, according to a recent study by Hafstead and Williams III (2018).

Climate Change Solution

Getting the solutions to Climate Change right is important, since the costs to industry and to millions of workers are so high. Economists are working on these solutions in ways that are easy to find. For example, there is now an academic journal devoted to this issue: it is called Climate Change Economics.

One of the journal’s most read articles is a 2010 paper on the economics of Hurricanes and Global Warming in the US, by William D. Nordhaus, an economist who was awarded the Swedish central banks prize in economics in honor of Alfred Nobel in 2018. Nordhaus calculates the incredibly high costs that hurricanes incur, something that’s only going to get worse with warmer climates.

On the topic of labour markets, a more recent article deals with the health and productivity effects of global warming on Chinese workers. The authors (Wang et al, 2020), find that

- The secondary (mining, energy) industry is most affected by pollution from a health perspective.

- Low-income groups suffer the largest loss of income due to pollution.

- A low carbon policy will improve air quality and economic equity.

Democracy Booster

When the Province of Quebec decided to ban the production of asbestos in 2011, it meant the permanent closure of large mines in the rural towns of Thetford Mines, and Asbestos. This mineral was in large demand for centuries, given its properties of strength, insulation, and heat resistance.

However, workers in these mines are prone to lung cancer and mesothelioma. For this reason, Europe and most of the world have banned the product.

Needless to say, it was a difficult decision, especially for these mono-industrial jobs, where there are not really other manufacturing or services jobs available. Getting political support from communities who will be ravaged by the industrial transition will be difficult but necessary. Green economics needs to keep this in mind when evaluating the overall effects of policies on the economy. People will vote against these policies if they feel there are no alternatives but loss of income.

Wrap-Up

Unemployment is a situation that occurs when you are jobless and looking for work. It is measured by a monthly survey issued by Statistics Canada, which also produces statistics on the labour markets such as the Unemployment Rate and the Participation Rate.

Cheat Sheet

Unemployment:

A situation that occurs when you are jobless and looking for work.

Unemployment Rate:

Percentage of people who are unemployed relative to the size of the labour market.

Participation Rate:

Percentage of people who are participating in the labour market, relative to the adult population.

Unfilled positions:

The number of jobs that are unfilled because there are not enough workers on the market. An indication of labour shortages.

References and Further Reading

Institut de la Statistique du Québec. (2018). Profils statistiques par région et MRC géographiques. Retrieved on 12 October 2018, from http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/profils/region_00/region_00.htm

Hafstead, M. A. C., & Williams III, R. C. (2018). Unemployment and environmental regulation in general equilibrium. Journal of Public Economics. Volume 160, April 2018, pp. 50-65.

National Film Board. (2009). GDP Project. http://gdp.nfb.ca/episode/1489/battered-in-durham-region

New York Times. (2010). Map of Unemployment in USA. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2009/03/03/us/20090303_LEONHARDT.html?ref=economy

Nordhaus, W. D. (2010). The Economics of Hurricanes and Implications of Global Warming. Climate Change Economics. Vol. 01, No. 01.

Wang, C. et. al. (2020). Economic Impacts of Climate Change and Air Pollution in China Through Health and Labor Supply Perspective: An Integrated Assessment Model Analysis. Climate Change Economics. Vol. 11, No. 1.

No Comments