Monopoly and Imperfect Competition

Why Should I Care?

Markets are not always perfect, and consumers sometimes pay too much for what they get. Producers will always try to “Cherry Pick” the best prices from consumers’ demand schedule.

This Lecture Has 3 Parts

- Monopoly

- Oligopoly

- Monopolistic Competition

Interview with Jean Francois Parent - on Monopolies and Competitive Markets

What is Imperfect Competition?

Some markets are more competitive than others. The level of competition is actually one of the most important factors that ensures a fair transaction. Of course there are rules, and regulations, that protect both buyers and sellers. But when you are the only game in town, either the only buyer (monopsony), or the only seller (monopoly), then you have more power over the outcome of the transaction.

Monopsony

Only buyer in a market with many sellers. For example, in a company town with a large employer, the company enjoys a monopsony position as the main buyer of labour. In a large city, workers have more choices and can choose to work in other factories or firms.

Monopoly

Only seller in a market with many buyers. For example, in a small town, there is usually only one grocery store which may hold monopoly power over the clientele. In a large city, clients can shop in several stores so that there is more competition.

Most of the time, there are way more buyers than sellers, so the monopoly is naturally the hot-ticket issue for consumer's interests. Health competition will ensure fair prices, but also fair treatment of clients, including quality of the product and post-transaction product service and support.

What makes an imperfect market? In simple terms, the number of producers determines the level of competition. One supplier is a monopoly, two producers is a duopoly, and three to eight producers is considered an oligopoly.

Why can this be a problem? When competition is low, suppliers can increase prices to increase their revenues, and their profits. We assume suppliers will always try to sell at the highest price possible, hoping to maximize their interests.

-

Monopoly

In the case of a monopoly, there is only one producer. In Latin, monopolium stems from mono (one), and polein, which means to sell. One company is now the only seller.

This producer can “cherry pick” the price-quantity combination that best suits him. The supplier compares the demand schedule to his costs. A monopolist will move supply to match the level of demand for a given price. By reducing supply (Qs), the monopolist can increase the price. Of course, his overall sales will drop, so its up to the monopolist to figure out the optimal combination of quantities, and price, to maximize his revenues.

There are no shortages or surplus in the monopoly scenario. The producer matches his Qs with the Qd he prefers. He picks a price-quantity combination that maximizes his revenues, or his profits (you can look into this in a more advanced course of micro-economics). The monopolist can move the supply to match the demand. This being said, the firm has to live with the parameters set by consumers. You can’t force people to buy more product and increase the price.

There is no supply curve, because that curve represents other suppliers coming to the market when the price is high (among other things). In this case, there are no other suppliers.

Scenario: The 100 villagers of VillageTown like ice-cream. But there is no ice-cream to be found. One of the older villagers, Grandma Jones, has an ice-cream machine and would like to try herself at this market. She buys her cream from the grocery store. She knows it costs her 1.50 $ to produce one tub of ice-cream. She also likes to keep some time off to play bridge with her friends. She does not know what else to do with her time though…

Costs = fixed costs + variable costs + opportunity cost

= kitchen equipment + ingredients + not playing bridge

If she’s wise, she will ask around and estimate how much people are ready to pay for ice-cream. She will also research how much ice-cream sells for in other villages. She draws a demand curve. She then has to decide how much to produce.

Using the Demand Schedule to Maximize Revenues

| Situation | Price | Quantity demanded (tubs/week) | Potential Spending ($) |

| A | 6 | 100 | 600 |

| B | 5 | 250 | 1250 |

| C | 4 | 300 | 1200 |

| D | 3 | 400 | 1200 |

| E | 2 | 500 | 1000 |

Grandma Jones looks at the demand schedule and she thinks: If I make 250 tubs, I can sell them for 5 $ each and receive 1,250 $ per week. Why make 300 or 400 tubs for a lower revenue?

Grandma Jones is so evil!

Let's look at it on the graph.

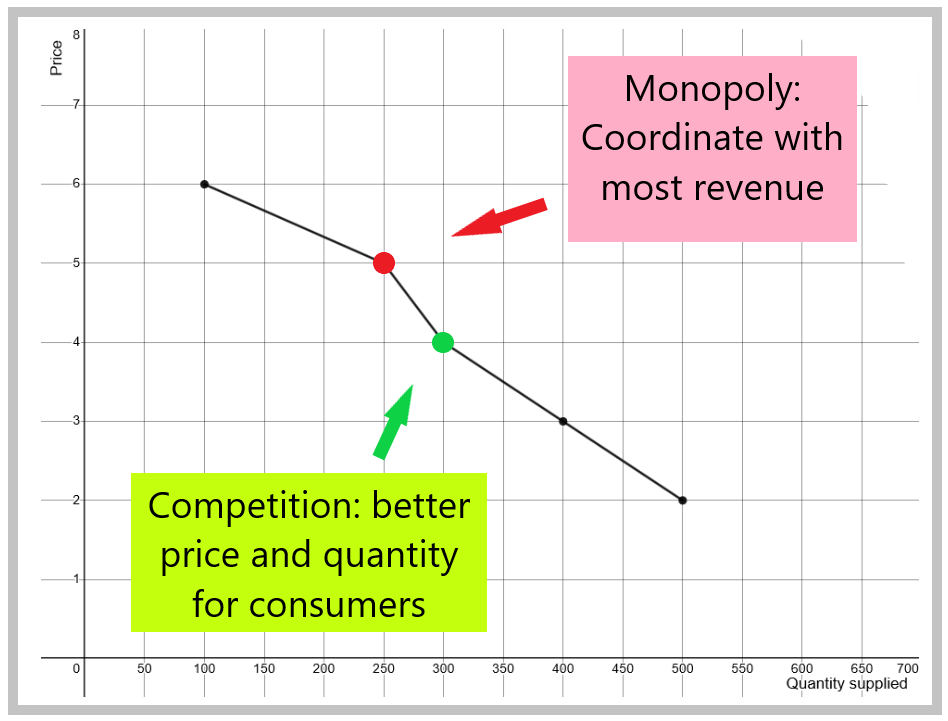

Graph - Grandma Jones Monopoly Position vs. Competition

Grandma Jones decides to "cherry pick" situation B (red dot), where the price (5 $) and quantity (250) from the demand schedule maximize her sales at 1,250 $.

Which situation would be better for the consumers? Situation E would be great because there would be lots of supply and low prices. However, it's hard to convince a private-sector monopolist to act this way. In actual fact, the best situation would be to have competition in the market. If we bring back the supply curve for the VillageTown ice cream industry, we find that the equilibrium would be at 4$ and 300 tubs per week. This would be better for consumers than letting Grandma Jones corner the market and spike the price.

There are several reasons why a monopoly would exist. Most times, a company feels it can benefit from industrial consolidation. This is a process that takes years, but can be very effective. In mature industries, the larger companies will buy smaller ones, to reduce the number of players in the market. In its final stages, consolidators will shut down production capacity to reduce supply and increase prices. A famous consolidator is General Motors, Corp. whose strategy worked rather well until competition rose from Japan and South Korea in the 1980's and 1990's.

Another reason for monopolies is innovation. If you are first-to-market, it takes some time before the competition can even start to produce. Companies often use patents to protect their inventions, which allows them to be a monopoly for up to 20 years. Pricing a new product can be difficult, since there are no comparable products on the market. How do you decide what the price of the iPad will be, before anyone even knows what an iPad is? First, you have to estimate a demand curve for a product people don’t even know. Second, you have to calculate the optimal price, which will maximize your sales revenues. Later, when competition arises on this new market, you will have to adjust your pricing to the open-market price.

Another reason for the existence of monopolies is the existence of barriers-to-entry. Some industries are difficult to enter, often because of very large capital requirements, such as building a rail road. The investment may be profitable over several decades, but the first years require tremendous investments. Other types of barriers can include cultural differences, regulations, and proprietary technology.

-

Oligopoly

In this scenario, there are usually half a dozen suppliers, who produce identical products (commodities) such as lumber, gas, or paper. They can be very competitive, or they could collaborate, which is called collusion, to the expense of consumers. Economists are not quite sure why some industries compete, and others collude. Ironically, if competition is too strong, and one of the players goes bankrupt, the industry automatically consolidates and may then become less competitive.

A) Collusion/Cartel

In this situation, producers collude and act as one producer. We call this a cartel. Usually, they agree not to compete on each other's exclusive territory, or in specific niche markets. Acting as one, as a monopoly, they “cherry pick” the most lucrative price-quantity combination. There is no supply curve in this scenario.

In VillageTown, a cartel could form if Grandma Jones’ bridge partners decide they want to join the industry and corner the market by setting prices when they meet for their weekly bridge game.

Examples of cartels (who were caught) include flat-screen TV manufacturers in Korea and Japan, the Montreal construction industry, and gasoline distribution in Central Quebec.

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2006/12/13/2003340302

B) Competition

In this situation, producers are not many, but they are competitive. You will see price differences, and each company will be present on each other's territory. If prices were to increase, the producers could not stop each other from increasing quantities supplied. They also could not stop new producers from entering the market. There is a supply curve because each player can't control the other players.

In VillageTown, a competitive scenario could hold even if there are only three producers. As long as Grandma Jones cannot control her bridge partners production strategy, the market is competitive. If the ladies keep their cards close to their vests, the game is on.

Examples of competitive oligopolies include mining companies, cable-TV service and cell phone service.

-

Monopolistic Competition

There is a third form of imperfect competition that accurately depicts many of our industries. It applies to a completely different set of products, those that are differentiated in an important way. Monopolistic Competition was coined by Joan Robinson, an important british economist and friend of JM Keynes.

Monopolistic competition occurs when firms are monopolists, in that their product is quite different from the rest of the industry. The product occupies it's own space, a "niche" in the market. As such, the monopolist is a price-maker, which means they have some control over their price, and can charge slightly more than in a purely competitive scenario. However, they are facing a competitive set of alternatives. If they over-charge, consumers can find substitutes to their product. For this reason, monopolistic competition does not lead to price-gouging.

For example, the iPad was a very innovative computer tablet. Apple had a monopoly on this product during its first year on the market (2010). However, the iPad is a close substitute to laptops and smartphones, so Apple cannot overcharge for this product.

In this scenario, only one supplier exists, because the product is sufficiently different that it has created its own market (niche market). But other products are possible substitutes, and so the niche market prices are limited to an implicit ceiling. The supplier can cherry-pick the optimal price-quantity combination, but with a very strict price ceiling imposed by substitution.

Later, other companies will make tablets, which means Apple is no longer in a monopolistic position. In any event, the level of competition is quite high.

In VillageTown, an example of this would be if one of Grandma Jones’ bridge partners decided to invent a new product, such as frozen yogurt. They would enjoy a small monopoly position, but couldn’t corner the market so much because people could easily go back to ice-cream if the price of frozen yogurt was too high. If the price of ice-cream is at 4.25$, that would be the ceiling, highest possible price, for frozen yogurt in VillageTown. As you can see on the graph below, the price of frozen yogurt would be 4$ (in red), or a little higher.

Wrap-Up

Markets are often imperfect, as suppliers use the demand curve to “cherry pick” the price-quantity combination that maximizes their revenues (sales).

Even if markets are imperfect, most of them are still relatively competitive. This does not mean the government does not have to regulate against cartels and monopolies.

Cheat Sheet

Monopoly:

A lone supplier that “cherry picks” the price-quantity combination that maximizes his revenues.

Oligopoly:

A small group of suppliers producing a commodity (non-differentiated product).

Cartel:

An oligopoly with collusion to fix prices and quantities at levels desired by the suppliers.

Monopolistic Competition:

A monopolist on a niche market. He cannot maximize his revenues because there is competition from substitute products (similar, but differentiated product).

References and Further Reading

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics.

Robinson, J. (1933). The Economics of Imperfect Competition.

No Comments