Bad Presentations

Bad Presentations

LEARNING OUTCOMES

- Discuss common mistakes in presentations

For many, the prospect of developing and delivering a business presentation rates right up there with death and taxes. Interestingly, that same mixture of fear and loathing is often felt by audience members as well. But it doesn’t have to be that way. The ability to craft a compelling story is a skill as old as the human race, and the need to communicate is as primal and potentially powerful.

Figure 1. Akhenaten as a sphinx, and was originally found in the city of Amarna.

For millions of years before the invention of modern technology, humans used the tools available to perpetuate traditions and culture and to document—and often rewrite—history. Do a few internet searches and immerse yourself in the Egyptian tombs; the caves of Chauvet; or El Castillo, the Temple of Kukulcan. What you’re experiencing is a feat of both artistry and communication. Although we don’t know the full significance of these early carvings and structures, there’s no doubt that these early humans captured their world view in a way that is still deeply resonant. While the tools have changed, the communication challenges—and opportunity—remain the same: to communicate an engaging and inspiring point of view.

Regardless of whether you want to change the world, build your brand, or build a billion-dollar business, effective presentation skills are essential. To quote legendary investor, philanthropist and Berkshire Hathaway chairman and CEO Warren Buffet, “If you can’t communicate and talk to other people and get across your ideas, you’re giving up your potential.”[1] As would be expected of a numbers person, Buffet has quantified his point in talks on student campuses and professional organizations. Speaking at his alma mater in 2009, Warren Buffett told Columbia Business School students that he believed learning effective communication skills could translate into 50 percent higher lifetime earnings.

Given our vibrant storytelling tradition and with so much at stake, why are there still so many bad presentations? Wouldn’t you think that modern communication technology—considering the advances in graphics and communications software alone!—would lead to more compelling presentations? Interestingly, the problem is, to some extent, the technology. It’s estimated that 30 million PowerPoint presentations are created every day, with (seemingly) a majority of presenters opting for default layouts and templates. The problem is, we’re wired for story, not bullet points. A related failure is our use of available technology.

Seth Godin has a wonderful—and instructive—rant on these points: Really Bad PowerPoint (and how to avoid it), blaming Microsoft wizards, templates, built-in clip art and lazy presenters for ineffective presentations. In response to a question regarding “death by PowerPoint” on the TechTarget Network, Margaret Rouse provided this definition: “a phenomenon cause by the poor use of presentation software,” identifying the primary contributors of this condition as “confusing graphics, slides with too much text and presenters whose idea of a good presentation is to read 40 slides out loud.”[2]

So how do we avoid causing “death by PowerPoint”—or by whatever presentation software we use? The common denominator of presentation mistakes is that they represent a failure of communication. This failure can be attributed to two errors: too much or too little. The error of too much is generally the result of trying to use slides as a teleprompter or a substitute to a report, or, it would seem, to bludgeon the audience into submission. Of course, this tends to have an alternate effect, namely, prompting audience members to walk out or tune out, turning their attention instead to doodling or their device of choice.

What bad presentations have too little of is emotion. Presentation expert and author of the classic Presentation Zen (and 4 related books) Gar Reynolds captures the crux of the problem: “a good presentation is a mix of logic, data, emotion, and inspiration. We are usually OK with the logic and data part, but fail on the emotional and inspirational end.”[3] There’s also a hybrid too little-too much mistake, where too little substance and/or no design sensibility is — in the mind of the presenter — offset by transitions and special effects. Heed Seth Godin’s advice: “No dissolves, spins or other transitions. None.”[4]

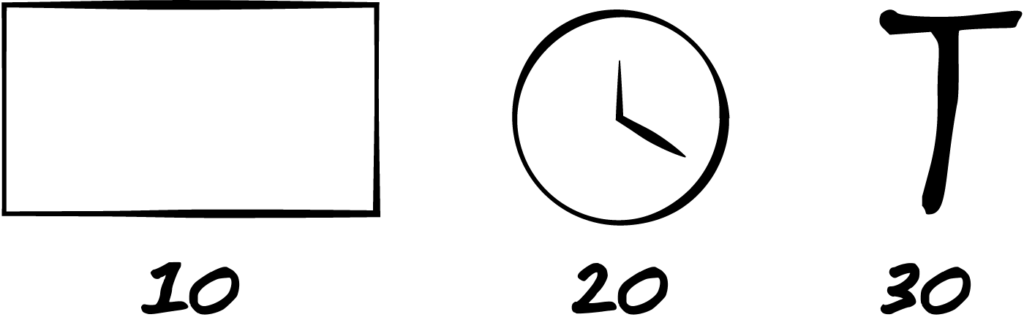

The 10/20/30 rule, generally attributed to venture capitalist Guy Kawasaki, is a good guideline to help you achieve a “just right” balance in your presentations. Geared for entrepreneurs pitching their business, his advice is a discipline that would improve the quality—and, effectiveness—of most presentations. In brief, 10/20/30 translates to a maximum of 10 slides, a maximum of 20 minutes and a minimum of 30 point font.[5]

Figure 2. Your presentation should have no more than 10 slides, take no more than 20 minutes, and use type no smaller than 30 point font.

While this rule is a good starting point, it doesn’t overrule your audience analysis or understanding of your purpose. Sometimes, you may need more slides or have a more involved purpose—like training people in new software or presenting the results of a research study—that takes more than 30 minutes to address. In that case, go with what your audience needs and what will make your presentation most effective. The concept behind the 10/20/30 rule—to make new learning easy for your audience to take in, process and remember—should still be your guide even if you don’t follow the rule exactly.

HOW TO AVOID DEATH BY POWERPOINT

For more on how to avoid causing death by PowerPoint, watch Swedish presentation expert and How to Avoid Death By PowerPoint author David Phillips TED Talk on the topic:

PRACTICE QUESTION

- Gallo, Carmine. "How Warren Buffet and Joel Osteen Conquered Their Terrifying Fear of Public Speaking," Forbes. May 16, 2013. ↵

- Rouse, Margaret. "What is death by PowerPoint?" TechTarget Network. ↵

- Reynolds, Garr. “10 tips for Improving Your Presentations Today,” Presentation Zen. Nov 2014. ↵

- Godin, Seth. Fix Your Really Bad PowerPoint. Ebook, sethgodin.com, 2001. ↵

- Kawasaki, Guy. The 10/20/30 Rule of PowerPoint. December 2005. ↵

No Comments