Creating Value in the Digital Age

Canadian media scholar Marshall McLuhan famously wrote that “the medium is the message” (McLuhan 1964). By this, he meant to emphasize that the characteristics of a medium (e.g., TV vs. print vs. internet) played an important role in communications, in addition to the message. We conclude this chapter by showing how the internet, as a medium, has played a transformative role in shaping the message and what this means for marketing.

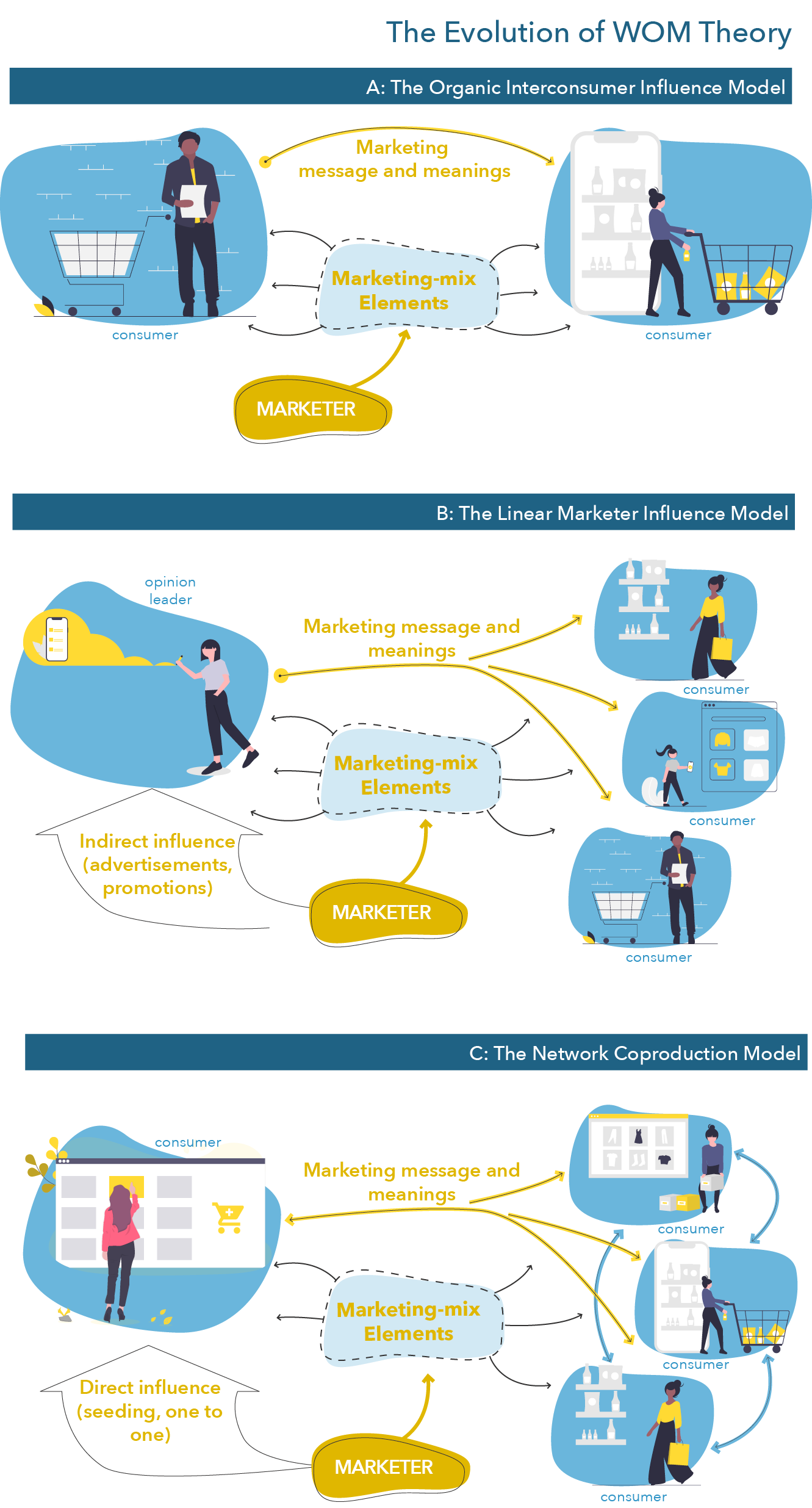

The ways messages are diffused to consumers have been vastly transformed since the 1950s. In reviewing word-of-mouth (WOM) models (Figure 1.1), Kozinets and co-authors (2010) identify three periods that are useful in conceptualizing how the diffusion of messages from firms to consumers has evolved.

Figure 1.1 The Evolution of WOM Theory

In the 1950s, the diffusion of messages echoed a view found in the very successful series Mad Men: advertising firms would create what they believed to be a message that could sell products and would use mass media such as TV, newspapers, magazines, and the radio to diffuse these messages. Word of mouth was organic, in the sense that it happened between consumers without interventions from firms. This is known as the organic interconsumer influence model.

In the 1970s, theories started to recognize that some individuals held more power than others to influence other consumers. Increasingly, these influential consumers and celebrities were leveraged by firms to diffuse their messages. This is known as the linear marketer influence model because in these earlier efforts, such influencers were believed to faithfully diffuse the message created by firms and their advertising agencies.

The emergence of the internet led to a third transformation in how we understand message diffusion and word of mouth and a movement toward a network co-production model. In this last model, consumers like you and me, online communities, and other types of networked forms of communication (such as publics created through hashtags, see Arvidsson and Caliandro 2015), have an increasing role to play not only in diffusing messages but also in transforming them.

Marketers have capitalized on this new mode of diffusion for messages by directly targeting influencers who are part of consumer networks and communities, which has resulted in the explosion of influencer marketing and the rising influence of micro-influencers. They have also developed capacities, such as social media monitoring, to identify emergent discourses on and around their brands, which sometimes completely reinterpret brand meanings.

The increased power of consumers in creating, modifying, and diffusing messages on and around brands has led, for example, to the creation of doppelgänger brand images, “a family of disparaging images and meanings about a brand that circulate throughout popular culture” (Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel 2006). Or, to simplify, consumers now create alternative campaigns that tarnish the intended image initially created by brands. Consumers using Twitter to diffuse alternative brand meanings or groups of consumers such as 4chan co-opting advertising campaigns are examples of this. For firms, the increased role of consumers in the creation and diffusion of messages has important implications for value creation: firms now have to consider not only how their messages can be amplified by consumers but also how they could be co-opted, reshaped, and resisted.

Another transformation brought about by the internet is media and audience fragmentation. In the 1970s, All in the Family was for a few years the top-watched TV show in the US. At its peak, it was watched by a fifth of the population. The 1980 finale of the hit series Dallas was watched by 90 million viewers, or more than 75% of the US television audience, while the last episode of M*A*S*H was watched by 105 million people. The last finale to make the top 10 list was Friends, in 2004, as the adoption of broadband internet accelerated.

Consumers have an increasing number of options for media-based entertainment. Traditional media companies are now competing against user-generated content found on social media websites such as Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok. Younger consumers have moved en masse to these new media, complicating the creation of advertising campaigns. Media fragmentation and the rise of internet in the lives of consumers has led to the emergence of the concept of the attention economy.

This is not a new concept. In 1971, Simon was already discussing how “information consumes … the attention of its recipients,” and Bill Gates was stating in 1996 that “content is king.” The implications for digital marketing had been recognized as early as the mid-1990s, when Mandel and Van der Leun mentioned in their book Rules of the Net how “attention is the hard currency of the cyberspace.” Goldhaber (1997) would add that “as the Net becomes an increasingly strong presence in the overall economy, the flow of attention will not only anticipate the flow of money but eventually replace it altogether.” This has led to a drastic rethinking of how to do marketing online and is intrinsically tied to the rise of inbound marketing and content marketing.

To recap, a few decades back, information was rather scarce; people, for the most part, consumed information from only a few sources, and companies could rather easily target consumers to diffuse their advertising messages. Nowadays, information is plentiful, consumers are diffused over a largely fragmented media ecosystem, and it has become more difficult for companies to diffuse their advertising messages to a mass of consumers, which can work against them. That difficulty, and the development of targeting technologies that have transformed how we can send messages to consumers, have led to two important transformations for marketers and how we understand value creation for consumers.

No Comments